Dinosaur Tumor Studied for Human Cancer Clues

Cancer in dinosaurs and illnesses in other animals are being studied in a groundbreaking new program that combines medical school with the study of natural history.

Educators hope the effort will produce doctors with a better understanding of why we get sick.

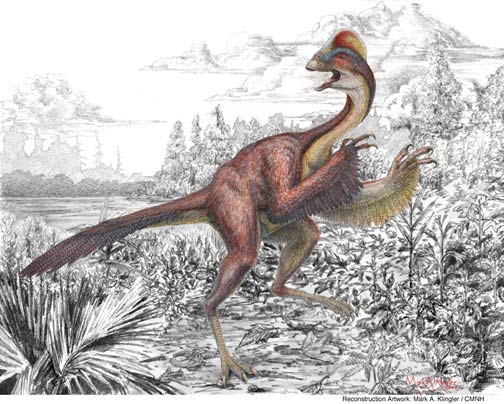

Despite being millions of years removed from our time and our own species, illnesses in animals like the dinosaurs can shed light on the evolution of human disease, says Christopher Beard, curator and specialist in vertebrate paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh.

"Some diseases that afflict humans today, such as malaria, gout, and cancer, are truly ancient and were handed down to us from our distant ancestors," Beard told LiveScience. "By studying the distribution of these diseases in other living and fossil organisms, we can gain insights into the nature of these diseases."

Part of the course

Students will now be offered the chance to learn about the history of disease as part of their regular medical school training, the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center announced recently.

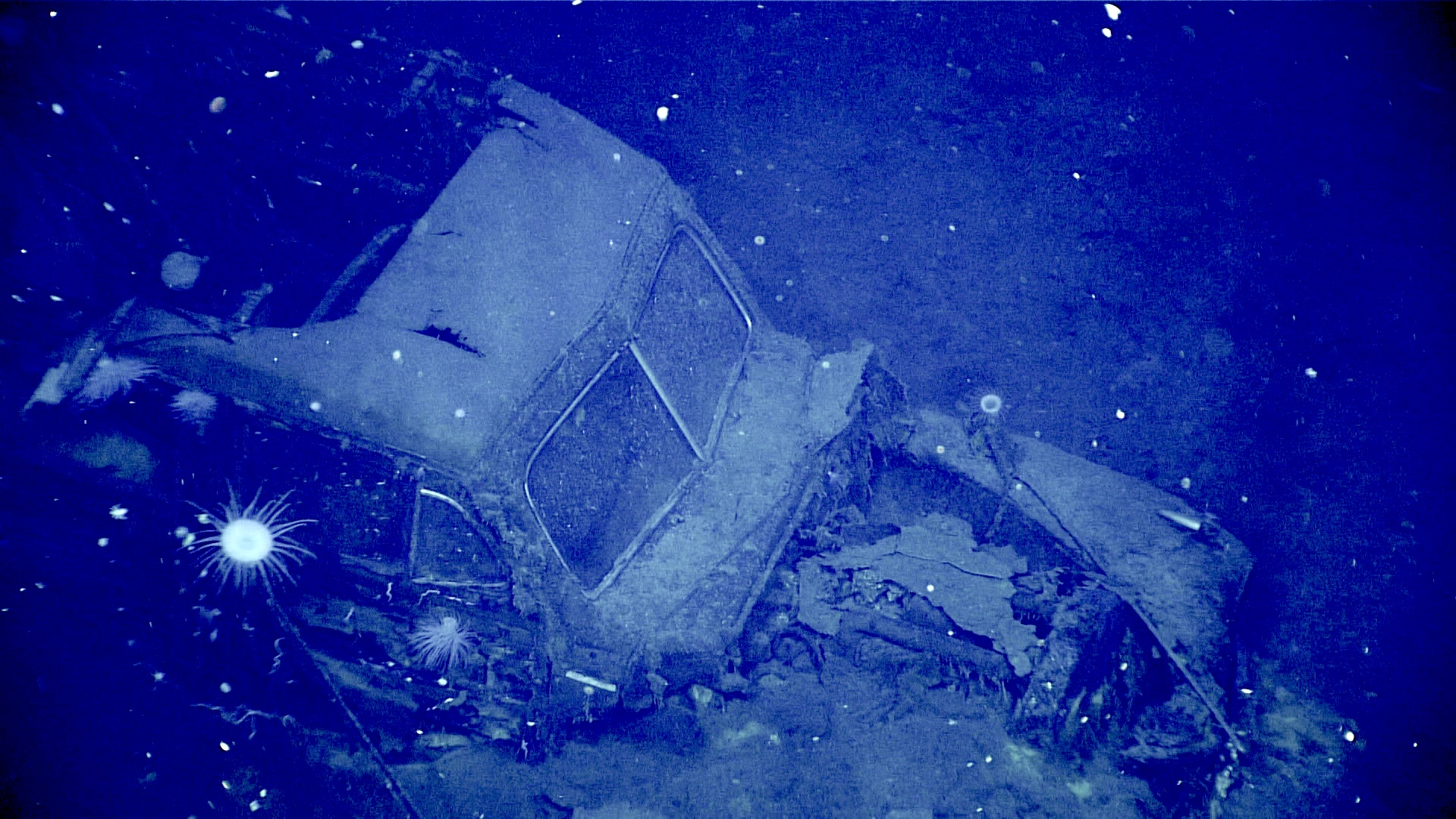

The university is welcoming four renowned curators from Carnegie Museum into its classrooms to teach seminars and use the museum collection, which is considered one of the world's premiere displays of natural history artifacts, for demonstrations. Included in the collection is a 150-million-year-old fossilized dinosaur bone complete with a tumor.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Finding a cancerous Jurassic lump doesn't surprise Michael Kennedy, a surgeon and professor at the University of Southern California. "Cancer is the most common cause of death in animals. It is not a uniquely human disease," he said in a recent telephone interview. The renewed focus on history in the teaching of medicine pleases Kennedy, also the author of "A Brief History of Disease, Science and Medicine" (Asklepiad Press, 2004), which describes the intricate historical links that connect diseases.

"History has traditionally been pushed aside in medical schools because it doesn't seem like a necessary part of the curriculum," he said. "But the history of disease has many practical applications today."

Backaches and the avian flu

Kennedy pointed to the current avian flu crisis as an example.

For several years now, health officials have been studying DNA extracted from frozen victims of the 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic buried in Alaska. According to Kennedy, they'll attempt to compare the deadly strain, which killed approximately 50 million people and was also thought to have jumped from birds to humans, to the contemporary flu to determine its potency.

The University of Pittsburgh's program will allow students to examine the birth of other familiar and modern health problems like back pain and hernias, which originated when humans began to walk upright about five million years ago.

"That evolutionary transformation radically altered the human skeleton, causing us to suffer many health problems that the typical mammalian quadruped doesn't have to worry about," Beard explained. "For example, chronic lower back pain in humans results from our peculiarly S-shaped vertebral column, which places extraordinary pressures on our lumbar vertebrae."

Help from apes

While the museum does not have any early human fossils in its collection, its wide variety of prehistoric primate specimens should provide enough clues about the earlier phases of human evolution to keep students busy, Beard said.

"These fossils, along with skeletons of living primates, will allow us to trace the major changes that have occurred in the human skeleton as we diverged from our close primate relatives."

Students interested in the field of sports medicine might take particular interest in this section of the museum, according to Beard.

"Some changes in the human skeleton that we often regard as being unique to us—such as our remarkably mobile shoulder joints that allow us to pitch baseballs and play golf—are actually features that we hold in common with our closest primate relatives, the apes," he said.

Related Stories

- Marine Mammals Suffer Human Diseases

- Maggots and Leeches: Old Medicine is New

- Top 7 Things Patients Expect from Doctors

Explore Dinosaurs

- Gallery: Dinosaur Fossils

- Dinosaurs that Learned to Fly

- The Biggest Carnivore: Dinosaur History Rewritten

- How Dinosaurs Might Have Walked

- A Brief History of Dinosaurs