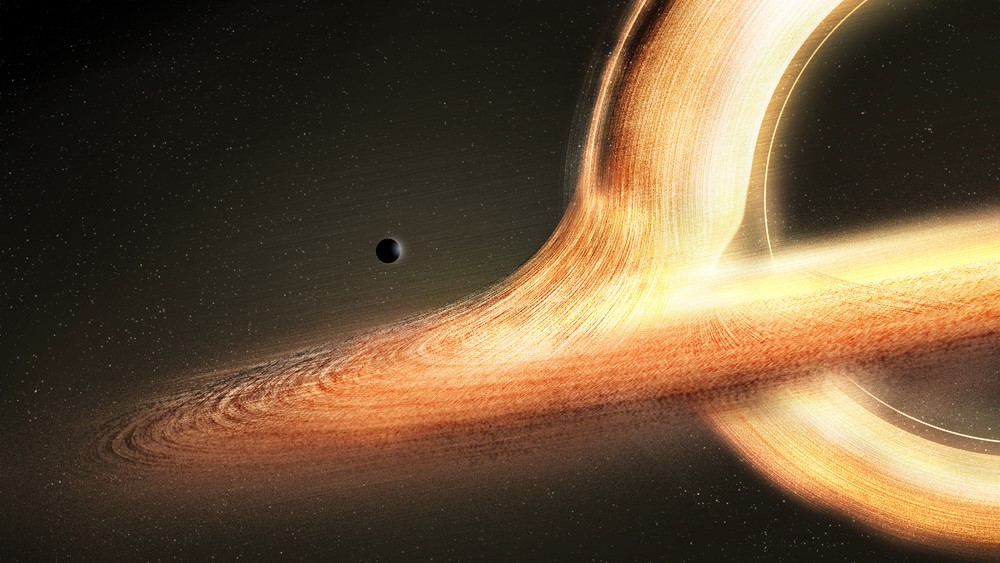

Monstrously huge black hole devours an Earth-size chunk of matter every second

It is so massive and bright that amateur astronomers can see it from Earth.

Astronomers have detected the brightest and fastest-growing black hole to have existed in the last 9 billion years. The enormous cosmic entity is 3 billion times more massive than the sun and swallows up an Earth-size chunk of matter every second.

The new supermassive black hole, known as J1144, is around 500 times as massive as Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the heart of the Milky Way, which was recently photographed for the first time. A ring of superhot plasma around the enormous void also emits around 7,000 times more light than our entire galaxy.

Australian astronomers discovered the cosmic juggernaut using data from Australian National University's SkyMapper Southern Sky Survey, which aims to map out the entirety of the sky in the Southern Hemisphere. Locating the supermassive black hole was like finding a "very large, unexpected needle in the haystack," the researchers said in a statement.

"Astronomers have been hunting for objects like this for more than 50 years," lead researcher Christopher Onken, an astronomer at the Australian National University (ANU) in Canberra, said in the statement. "They have found thousands of fainter ones, but this astonishingly bright one had slipped through unnoticed."

Related: Ultra-rare black hole ancestor detected at the dawn of the universe

The black hole's voracious appetite dwarfs that of other similarly huge supermassive black holes. Normally, the growth rates of these enormous cosmic entities slow down as they become more massive, according to the statement. This is likely due to increased Hawking radiation — thermal radiation that is theorized to be released from black holes due to the effects of quantum mechanics.

The newfound black hole eats up so much matter that its event horizon — the boundary past which nothing, including light, can escape — is unusually wide. "The orbits of the planets in our solar system would all fit inside its event horizon," co-author Samuel Lai, an ANU astronomer, said in the statement.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Black holes cannot be seen because they do not give off any light. But astronomers can spot black holes because their intense gravity pulls matter towards the event horizon so quickly that this matter gets turned into super hot plasma; this gives off light in a ring around the black hole, called an accretion disk. The newly discovered behemoth's accretion disk is the brightest that astronomers have ever detected, due to its massive event horizon and the extreme speed at which it pulls in matter. Researchers are "fairly confident" that this is a record that will never be broken, according to the statement.

The black hole boundary is so bright that even amateur astronomers would be able to see it with a powerful enough telescope trained at exactly the right part of the sky, the researchers said.

The team is now trying to determine why the massive black hole remains so unusually hungry for matter. The scientists suspect that a catastrophic cosmic event must be responsible for the birth of this gargantuan void. "Perhaps two big galaxies crashed into each other, funneling a whole lot of material onto the black hole to feed it," Onken said.

However, it may be hard to find out exactly how it formed. The researchers are skeptical that we will ever find another similarly massive and rapidly expanding black hole ever again, making it hard to test a general theory about the formation of such voracious cosmic objects.

"This black hole is such an outlier that while you should never say never, I don't believe we will find another one like this," co-author Christian Wolf, an ANU astronomer and group leader of SkyMapper, said in the statement. "We have essentially run out of sky where objects like this could be hiding."

However, some researchers predict that there are as many as 40 quintillion black holes in the universe, which could account for around 1% of all matter in the universe, so the odds that there may still be an even more ravanous black hole out there somewhere are not zero.

The study was submitted June 8 to the preprint databaser arXiv but has not yet been peer-reviewed. If accepted, it will be published in the journal Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia.

Originally published on Live Science.

Harry is a U.K.-based senior staff writer at Live Science. He studied marine biology at the University of Exeter before training to become a journalist. He covers a wide range of topics including space exploration, planetary science, space weather, climate change, animal behavior and paleontology. His recent work on the solar maximum won "best space submission" at the 2024 Aerospace Media Awards and was shortlisted in the "top scoop" category at the NCTJ Awards for Excellence in 2023. He also writes Live Science's weekly Earth from space series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus