What's the difference between race and ethnicity?

Race and ethnicity are terms that are sometimes used sloppily, almost interchangeably. But race and ethnicity are not the same thing.

Race and ethnicity are both terms that describe human identity, but in different — if related — ways. Identity might bring to mind questions of skin color, nationality, language, religion, cultural traditions or family ancestry. Both race and ethnicity encompass many of these descriptors.

"'Race' and 'ethnicity' have been and continue to be used as ways to describe human diversity," said Nina Jablonski, an anthropologist and paleobiologist at The Pennsylvania State University, who is known for her research into the evolution of human skin color. "Race is understood by most people as a mixture of physical, behavioral and cultural attributes. Ethnicity recognizes differences between people mostly on the basis of language and shared culture."

Related: Why did some people become white?

In other words, race is often perceived as something that's inherent in our biology, and therefore inherited across generations. Ethnicity, on the other hand, is typically understood as something we acquire, or self-ascribe, based on factors like where we live or the culture we share with others.

But just as soon as we've outlined these definitions, we're going to dismantle the very foundations on which they're built. That's because the question of race versus ethnicity actually exposes major and persistent flaws in how we define these two traits, flaws that — especially when it comes to race — have given them an outsized social impact on human history.

Nina G. Jablonski is a professor of Anthropology at Pennsylvania State University. Her research on human adaptations to the environment centers on the evolution of human skin and skin pigmentation, as well as understanding the history and social consequences of skin-color-based race concepts. She has published several books, including “Living Color: The Biological and Social Meaning of Skin Color” (University of California Press, 2014) and “Skin: A Natural History” (University of California Press, 2008), and has given a TED Talk, called “Skin Color is an Illusion.”

What is race?

The idea of "race" originated from anthropologists and philosophers in the 18th century, who used geographic regions and phenotypic traits like skin color to place people into different racial groupings, according to Britannica. That not only cemented the notion that there are separate racial "types" but also fueled the idea that these differences had a biological basis.

That flawed principle laid the groundwork for the belief that some races were superior to others — which white Europeans used to justify the slave trade and colonialism, entrenching global power imbalances, as reported by University of Cape Town emeritus professor Tim Crowe at The Conversation.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We can't understand race and racism outside of the context of history, and more importantly economics. Because the driver of the triangular trade [which included slavery] was capitalism, and the accumulation of wealth," said Jayne O. Ifekwunigwe, a medical anthropologist at the Center on Genomics, Race, Identity, Difference (GRID) at the Social Science Research Institute (SSRI), Duke University. She is also the associate director of engagement for the Center on Truth, Racial Healing & Transformation (TRHT) at Duke. The center is part of a movement across the United States whose members lead events and discussions with the public to challenge historic and present-day racism.

The effects of this history prevail today — even in current definitions of race, where there's still an underlying assumption that physical characteristics like skin color or hair texture have biological, genetic underpinnings that are completely unique to different racial groups, according to Stanford. Yet, the scientific basis for that premise simply isn't there.

"If you take a group of 1,000 people from the recognized 'races' of modern people, you will find a lot of variation within each group," Jablonski told Live Science. But, she explained, "the amount of genetic variation within any of these groups is greater than the average difference between any two [racial] groups." What's more, "there are no genes that are unique to any particular 'race,'" she said.

Related: What are genes?

Jayne O. Ifekwunigwe is a senior research scholar in the Center for Genomics, Race, Identity, Difference at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. As a critical and global ‘mixed race’ studies pioneer, Ifekwunigwe researches anthropological interpretations of both constructs of race as well as ‘mixed race’ and social interfaces between conceptualizations of biology and culture. Ifekwunigwe is author of “Scattered Belongings: Cultural Paradoxes of Race, Nation and Gender” (Routlege, 1999) as well as multiple journal papers.

In other words, if you compare the genomes of people from different parts of the world, there are no genetic variants that occur in all members of one racial group but not in another. This conclusion has been reached in many different studies. Europeans and Asians, for instance, share almost the same set of genetic variations. As Jablonski described earlier, the racial groupings we have invented are actually genetically more similar to each other than they are different — meaning there's no way to definitively separate people into races according to their biology.

Jablonski's own work on skin color, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2010, demonstrates this. "Our research has revealed that the same or similar skin colors — both light and dark — have evolved multiple times under similar solar conditions in our history," she said. "A classification of people based on skin color would yield an interesting grouping of people based on the exposure of their ancestors to similar levels of solar radiation. In other words, it would be nonsense." What she means is that as a tool for putting people into distinct racial categories, skin color — which evolved along a spectrum — encompasses so much variation within different skin color "groupings" that it's basically useless, she said during a TED Talk in 2009.

We do routinely identify each other's race as "Black," "white" or "Asian," based on visual cues. But crucially, those are values that humans have chosen to ascribe to each other or themselves. The problem occurs when we conflate this social habit with scientific truth — because there is nothing in individuals' genomes that could be used to separate them along such clear racial lines.

In short, variations in human appearance don't equate to genetic difference. "Races were created by naturalists and philosophers of the 18th century. They are not naturally occurring groups," Jablonski emphasized.

What is ethnicity?

This also exposes the major distinction between race and ethnicity: While race is ascribed to individuals on the basis of physical traits, ethnicity is more frequently chosen by the individual. And, because it encompasses everything from language to nationality, culture and religion, it can enable people to take on several identities. Someone might choose to identify themselves as Asian American, British Somali or an Ashkenazi Jew, for instance, drawing on different aspects of their ascribed racial identity, culture, ancestry and religion.

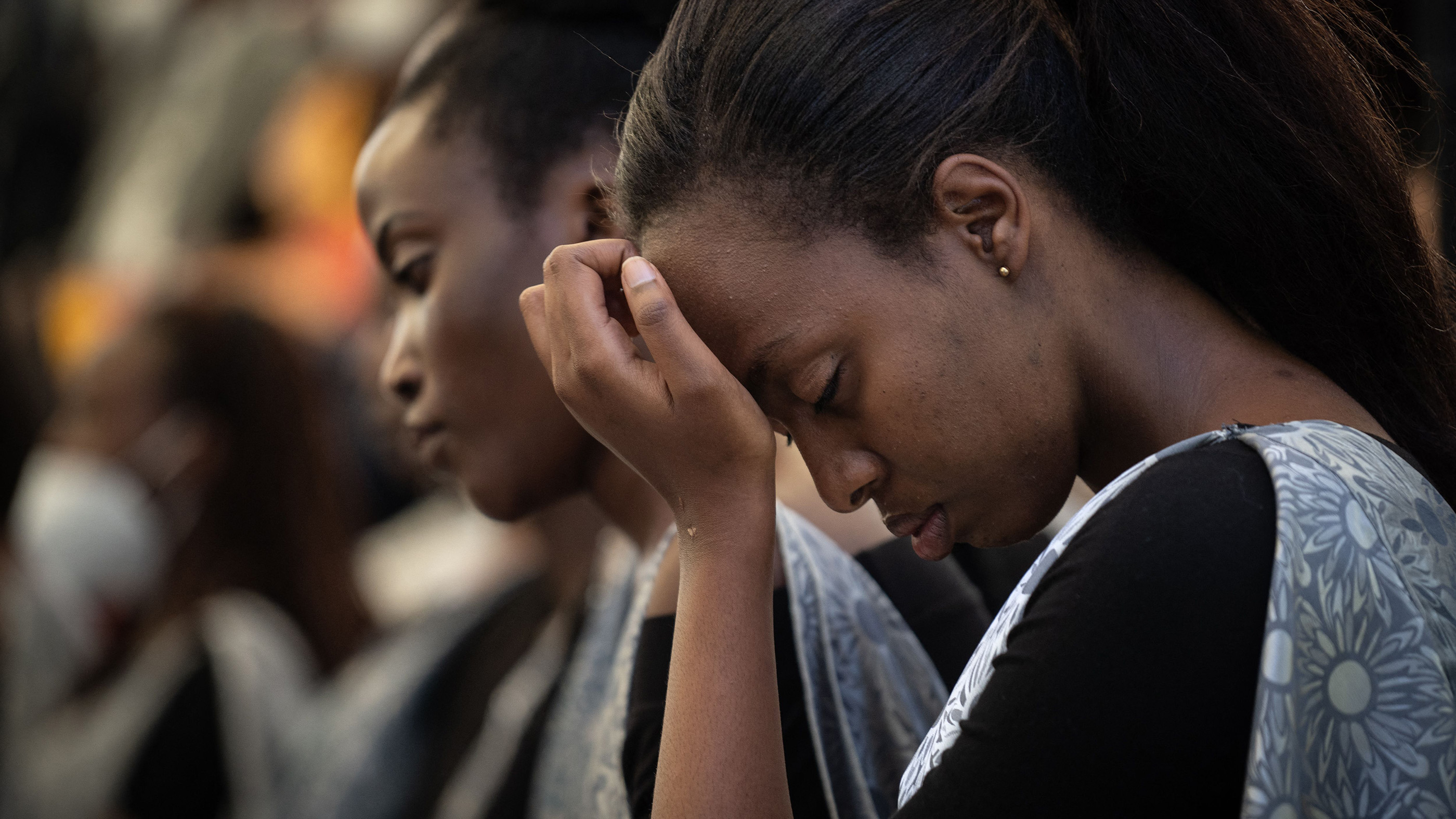

Ethnicity has been used to oppress different groups, as occurred during the Holocaust, or within interethnic conflict of the Rwandan genocide, where ethnicity was used to justify mass killings. Yet, ethnicity and ethnic groups can also be a boon for people who feel like they're siloed into one racial group or another, because it offers a degree of agency, Ifekwunigwe said.

"That's where this ethnicity question becomes really interesting, because it does provide people with access to multiplicity," she said. (That said, those multiple identities can also be difficult for people to claim, such as in the case of multiraciality, which is often not officially recognized.)

Ethnicity and race are also irrevocably intertwined — not only because someone's ascribed race can be part of their chosen ethnicity but also because of other social factors.

"If you have a minority position [in society], more often than not, you're racialized before you’re allowed access to your ethnic identity," Ifekwunigwe said. "That's what happens when a lot of African immigrants come to the United States and suddenly realize that while in their home countries, they were Senegalese or Kenyan or Nigerian, they come to the U.S. — and they're Black." Even with a chosen ethnicity, "race is always lurking in the background," she said.

These kinds of problems explain why there's a growing push to recognize race, like ethnicity, as a cultural and social construct, according to the RACE Project.

Yet in reality, it's not quite so simple.

Impact of race and ethnicity

Race and ethnicity may be largely abstract concepts, but that doesn't override their very genuine, real-world influence. These constructs wield "immense power in terms of how societies work," said Ifekwunigwe. Defining people by race, especially, is ingrained in the way that societies are structured, how they function and how they understand their citizens: Consider the fact that the U.S. Census Bureau officially recognizes five distinct racial groups, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

The legacy of racial categories has also shaped society in ways that have resulted in vastly different socioeconomic realities for different groups. That's reflected, for instance, in higher levels of poverty for minority groups, poorer access to education and health care, and greater exposure to crime, environmental injustices and other social ills. What's more, race is still used by some as the motivation for continued discrimination against other groups that are deemed to be "inferior," the Southern Poverty Law Center explained.

"It's not just that we have constructed these [racial] categories; we have constructed these categories hierarchically," Ifekwunigwe said. "Understanding that race is a social construct is just the beginning. It continues to determine people's access to opportunity, privilege and also livelihood in many instances, if we look at health outcomes," she said. One tangible example of health disparity comes from the United States, where data shows that African American women are more than twice as likely to die in childbirth compared with white women, the Census Bureau reported.

Perceptions of race even inform the way we construct our own identities — though this isn't always a negative thing. A sense of racial identity in minority groups can foster pride, mutual support and awareness. Even politically, using race to gauge levels of inequality across a population can be informative, helping to determine which groups need more support, because of the socioeconomic situation they’re in. As the U.S. Census Bureau website explains, having data about people's self-reported race "is critical in making policy decisions, particularly for civil rights."

All this paints a complex picture, which might leave us pondering how we should view the idea of race and ethnicity. There are no easy answers, but one thing is clear: While both are portrayed as a way to understand human diversity, in reality they also wield power as agents of division that don't reflect any scientific truths.

Science does show us that across all the categories that humans construct for ourselves, we share more in common than we don't. The real challenge for the future will be to see that instead of our "differences" alone.

Additional resources

For a deeper understanding of how the U.S. government categorizes race and ethnicity, read "Research to Improve Data on Race and Ethnicity," which traces how the Census bureau is working to keep up with individuals' understanding of their own identities. (Hint: It's usually complex.) The nonpartisan Pew Research Center has a landing page for its research and survey data related to race and ethnicity, which touches on topics as diverse as immigration, health, and education.

As is easy to imagine for such a hot topic, mountains of books have been written about issues around race and ethnicity. "Superior: The Return of Race Science" (Beacon Press, 2019) by Angela Saini Beacon tracks the history of scientific racism and the ways discredited ideas still influence scientific fields today. "Genetics and the Unsettled Past: The Collision Between DNA, Race, and History" (Rutgers University Press, 2013), is a scholarly look at how the field of genetics has complicated how we talk about genetics and history. Isabel Wilkerson's "Caste: The Origins of our Discontents" (Random House, 2020) explores how race and ethnicity are used to divide people into hierarchies.

Bibliography

Bibliography

"About the topic of race." U.S. Census Bureau. Dec. 3, 2021.

"Racism and Health." Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. November 24, 2021.

"What Racism Costs Us All." Finance & Development, International Monetary Fund. Fall 2020.

(2014, July 31). A New African American Identity: The Harlem Renaissance. Smithsonian. https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/new-african-american-identity-harlem-renaissance

Roberts, Frank Leon. (2018, July 13). How Black Lives Matter Changed the Way Americans Fight for Freedom. ACLU. https://www.aclu.org/blog/racial-justice/race-and-criminal-justice/how-black-lives-matter-changed-way-americans-fight

White Nationalist. Southern Poverty Law Center. https://www.splcenter.org/fighting-hate/extremist-files/ideology/white-nationalist

Newkirk II, Vann R. (2018, Feb. 28). Trump’s EPA Concludes Environmental Racism Is Real. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2018/02/the-trump-administration-finds-that-environmental-racism-is-real/554315/

American Psychological Association. Ethnic and Racial Minorities & Socioeconomic Status. https://www.apa.org/pi/ses/resources/publications/minorities

(2019, June 10). Ethnic Cleansing. The History Channel. https://www.history.com/topics/holocaust/ethnic-cleansing

Smedley, Audrey, The history of the idea of race. Britannica. Accessed April 9, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/topic/race-human/Scientific-classifications-of-race

Jablonski, Nina and Chaplin, George. (2010, May 5). Human skin pigmentation as an adaptation to UV radiation. PNAS. https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.0914628107

Originally published on Live Science on Feb. 8, 2020 and updated on April 9, 2022.

Emma Bryce is a London-based freelance journalist who writes primarily about the environment, conservation and climate change. She has written for The Guardian, Wired Magazine, TED Ed, Anthropocene, China Dialogue, and Yale e360 among others, and has masters degree in science, health, and environmental reporting from New York University. Emma has been awarded reporting grants from the European Journalism Centre, and in 2016 received an International Reporting Project fellowship to attend the COP22 climate conference in Morocco.

- Stephanie PappasLive Science Contributor