Students Recall More Hollywood than History

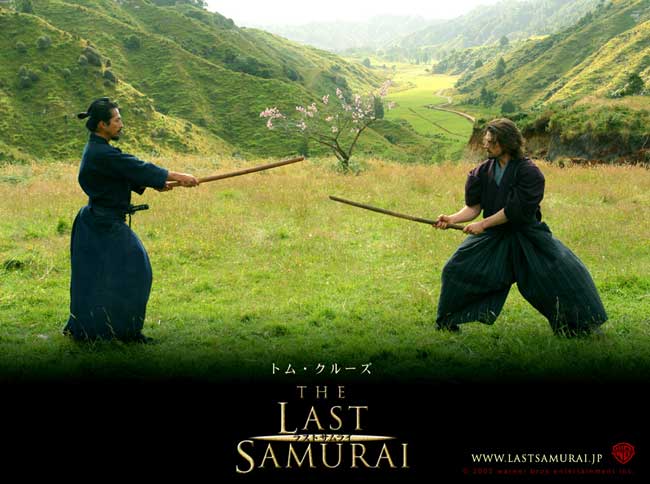

If you thought Tom Cruise's character in "The Last Samurai" represented a real figure from history, you were wrong. But don't feel ashamed. A new study shows that even students, with facts staring them in the face, tend to substitute Hollywood fiction for historical fact in their minds.

"What we found is that there's something really special about watching a film that lets people retain information from that film, even when they had read a contradictory account in the textbook," said Andrew Butler, a psychology researcher at Washington University in St. Louis during the time he and his colleagues conducted the study.

There's a positive flip-side to this memory for movies: Researchers also found that historically accurate films can actually boost student learning alongside the usual textbook reading. That represents the good news for history teachers who screen Hollywood fare such as "Elizabeth," "Marie Antoinette" or "U-571" in their classrooms, because films apparently stick in students' memories regardless of whether they are right or wrong.

Warning: This film is ...

Films that gloss over some truths could still prove useful viewing, as long as teachers warn students beforehand about the specific historical inaccuracies. General warnings about films being inaccurate proved about as useful as no warning at all.

Two experiments involving 108 students had different groups watch film clips from nine different movies. Students also read an accurate historical text blurb relating to each of the movies, and received different levels of warnings regarding the accuracy of the films.

The power of Hollywood clearly emerged when the film's historical information matched the information in the text. Students who watched such film clips had about 50 percent greater correct recall of facts a week later, as opposed to students who just read a text.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But when the film's information contradicted the text, students often wrongly recalled the misinformation up to half the time. Many students expressed their wrong information confidently, and sometimes even misattributed the source of their information as coming from the text, rather than from the film.

Only having the specific warning ahead of time reduced the misinformation effect, which previous studies have also found. Even so, researchers cautioned that future studies would have to examine whether the warning sticks in students' memories for more than a week.

"Over time, it may be that they forget about the warning and just retain that [wrong] information," Butler told LiveScience. The current study is forthcoming in the journal Psychological Science.

Hollywood as sole source

Butler plans to conduct follow-up studies on the power of film as a postdoctoral researcher at Duke University in North Carolina. One study would even have participants either watch a movie or read a screenplay, and gauge the different effects of film versus text on memory recall.

"There is nothing wrong with what Hollywood is doing, because these are supposed to be entertaining films," Butler said. "But people should be aware, because for the vast majority of the American public, all they know about some of these specialized topics is what they see in the movie theater."

Keep in mind that such specialized topics may easily run the gamut from history to science. For now, moviegoers might do well to take the Hollywood words "inspired by true events" with a very large pinch of salt.

- The Top 10 Infectious Movies

- Top 10 Scariest Movies Ever

- 10 Ways to Keep Your Mind Sharp