First-Ever Image of the 'Cosmic Web' Reveals the Gassy Highway That Connects the Universe

Everything really is connected, man.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

In the cold wilderness of space, galaxies huddle together around the campfires of stars and the assuring pull of supermassive black holes. Between these cozy clusters of galaxies, where empty space stretches on for millions of light-years all around, a faint highway of gas bridges the darkness.

This gassy, intergalactic network is known in cosmological models as the cosmic web. Made of long filaments of hydrogen left over from the Big Bang, the web is thought to contain most (more than 60%) of the gas in the universe and to directly feed all of the star-producing regions in space. At the intersections where filaments overlap, galaxies appear. At least, that's the theory.

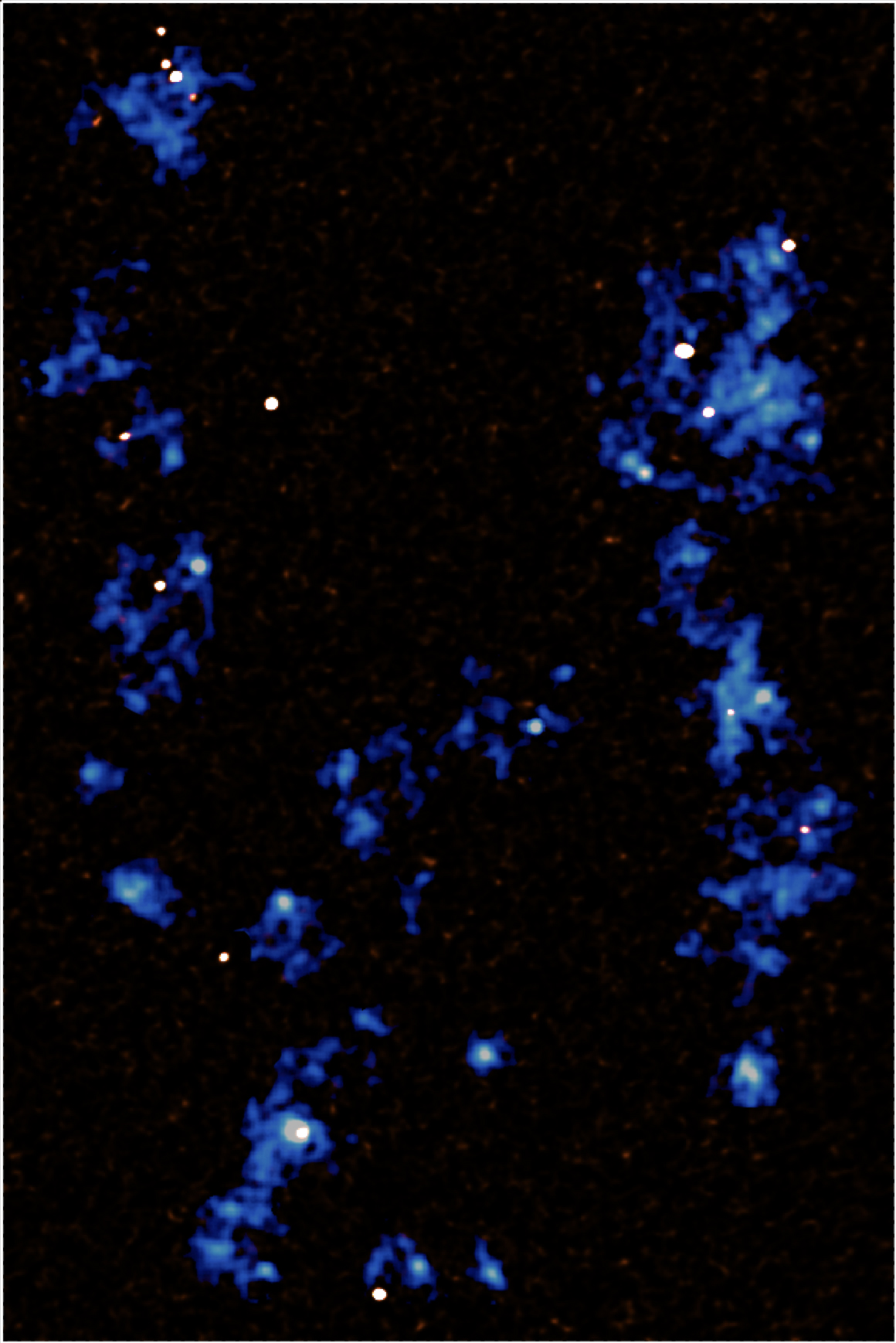

The filaments of the galactic web have never been directly observed before, because they are among the faintest structures in the universe and are easily overshadowed by the glow of the galaxies around them. But now, in a study published today (Oct. 3) in the journal Science, researchers have cobbled together the first-ever photograph of cosmic filaments converging on a faraway galaxy cluster, thanks to some of the most sensitive telescopes on Earth.

The image (below) shows blue filaments of hydrogen crisscrossing through a cluster of ancient white galaxies, located about 12 billion light-years away from Earth (meaning the galaxies were born in roughly the first billion and a half years after the Big Bang). Gently lit by the ultraviolet glow of the galaxies themselves, the filaments stretch on for more than 3 million light-years, confirming their status as some of the most gargantuan structures in space.

"These observations of the faintest, largest structures in the universe are a key to understanding how our universe evolved through time," Erika Hamden, an astronomer at the University of Arizona's Steward Observatory, wrote in an accompanying commentary on the new study. (Hamden was not involved in the research.) These observations, Hamden added, are "just the tip of the iceberg" of cosmic web detection, with research revealing further images of the web in other ancient corners of space.

Connecting to the web

As the new study notes, the wisps of hydrogen that make up the cosmic web's filaments are so faint they are barely distinguishable from the empty sky. So, how did the researchers manage to coax these features out of the darkness? By using the galaxies within the web "as cosmic flashlights," Hamden wrote.

Using an instrument called the Multi Unit Spectroscopic Explorer on the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope, the researchers zoomed in on an ancient clump of galaxies located in the Aquarius constellation, known for being both extremely vast and extremely old. Light from newborn stars and matter-shredding black holes faintly illuminated the wisps of hydrogen swirling in and between these galaxies, allowing the researchers to map a vague outline of the cosmic web's filaments there.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The observations revealed two parallel highways of hydrogen connecting the galactic dots over millions of light-years, bridged by a third stream of gas connecting them diagonally like a cosmic off-ramp. True to cosmological models, the filaments of gas seemed to directly feed the most active star-forming galaxies on the grid, pumping hydrogen right into the homes of newborn suns and hungry black holes.

This study provides the most convincing evidence yet that the cosmic web exists, just as models predict, Hamden wrote. However, the study of structures so faint and far away has obvious limitations. For one, it's almost impossible to tell where the edges of each hydrogen filament end and empty space begins, which enables different researchers to define the boundaries of filaments differently, potentially resulting in different pictures of the structures. In addition, ground-based telescopes can detect filaments from only the most distant, ancient galaxy clusters, which emit enough light to reveal how the cosmic web appeared shortly after the Big Bang.

A space-based UV telescope could open the door to studying how the web connects to younger, fainter galaxies, but deploying such an instrument would be difficult and expensive, Hamden wrote. Ultimately, this new study doesn't put the stargazers of Earth any closer to the ancient and mysterious worlds across the universe — but it does remind us that we may be more connected to them than we thought.

- The 12 Strangest Objects in the Universe

- 15 Unforgettable Images of Stars

- 9 Strange Excuses for Why We Haven't Met Aliens Yet

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus