'Medieval' nanotech chainmail sports 100 trillion chemical bonds per square centimeter — and could be the future of armor

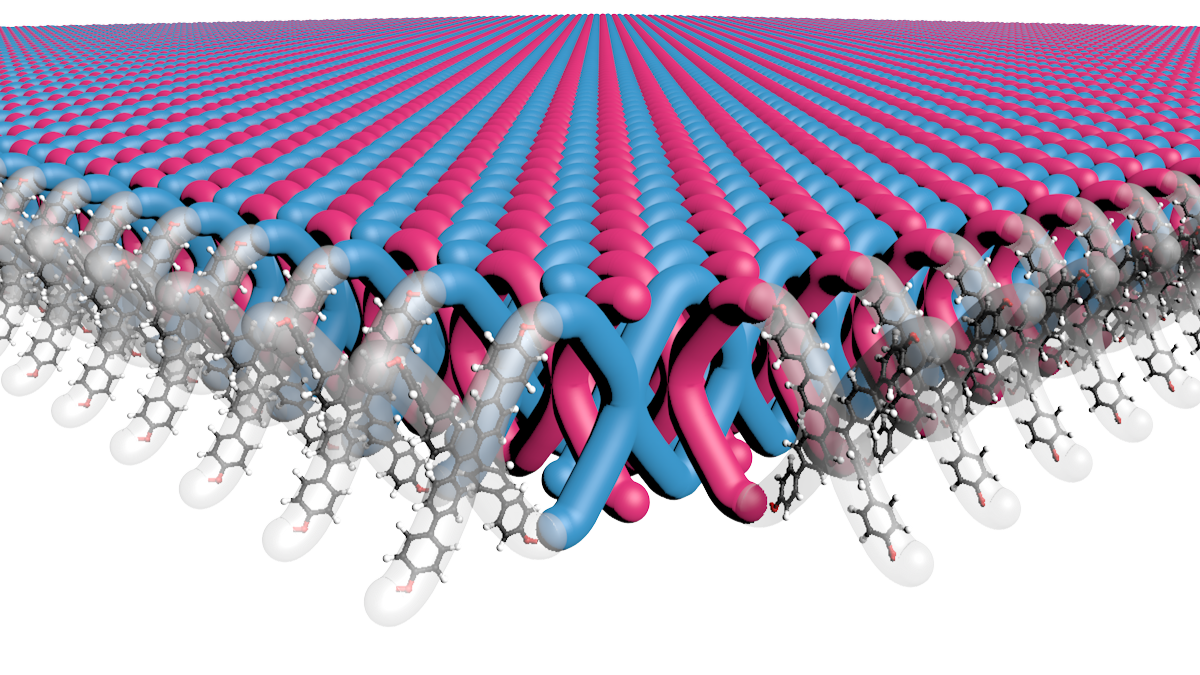

Researchers unveiled a super-strong nanoscale material made from the first two-dimensional mechanically interlocked polymers. The material resembles medieval chainmail at the molecular level and could be used in body armor.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Chemists have invented a new material that could be the future of body armor — chainmail. But this isn't the Middle Ages all over again; the new super-strong material is made of molecules that are interlocked on a nanoscale, scientists say.

Researchers fused lines of molecules like links in a chain to create sheets of the world's first two-dimensional mechanically interlocked material (2D MIM), which has length and width. The material contains 100 trillion chemical bonds per square centimeter (around 650 trillion per square inch), which is the highest density of mechanical bonds ever achieved, the researchers reported in the study, published Jan. 16 in the journal Science.

The study authors added a small amount of the material to a tough plastic material called Ultem — also made from molecule chains. Ultem is already incredibly strong but became even stronger with the 2D MIM. The research, which could eventually be used in body armor, was partly funded by the government's Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency.

"It's similar to chainmail in that it cannot easily rip because each of the mechanical bonds has a bit of freedom to slide around," study co-author William Dichtel, a chemistry professor at Northwestern University in Illinois, said in a statement. "If you pull it, it can dissipate the applied force in multiple directions. And if you want to rip it apart, you would have to break it in many, many different places."

The 2D MIM material is made of interlocked polymers, which are long chains of smaller molecules, called monomers. The team took lines of X-shaped monomers and arranged them into crystal structures that react together so that the ends of the monomers bond with the ends of other monomers, according to the statement.

Each monomer's X-shape left gaps in which researchers could weave additional lines of these molecular building blocks, creating layers of interlocked 2D polymers within the crystals. The scientists then dissolved the crystals to retrieve the interlocked polymers.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"After the polymer is formed, there's not a whole lot holding the structure together," Dichtel said. "So, when we put it in solvent, the crystal dissolves, but each 2D layer holds together. We can manipulate those individual sheets."

To test their new material, the researchers made composite materials out of 97.5% Ultem fiber and 2.5% 2D MIM. The small amount of interlocked 2D polymer increased the force needed to deform Ultem fibers by 45% and the amount of stress the Ultem could withstand by 22%, according to the study.

"We have a lot more analysis to do, but we can tell that it improves the strength of these composite materials," Dichtel said. "Almost every property we have measured has been exceptional in some way."

Patrick Pester is the trending news writer at Live Science. His work has appeared on other science websites, such as BBC Science Focus and Scientific American. Patrick retrained as a journalist after spending his early career working in zoos and wildlife conservation. He was awarded the Master's Excellence Scholarship to study at Cardiff University where he completed a master's degree in international journalism. He also has a second master's degree in biodiversity, evolution and conservation in action from Middlesex University London. When he isn't writing news, Patrick investigates the sale of human remains.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus