Who was Charlemagne, the Carolingian Emperor of Europe?

Charlemagne was a Middle Ages king who founded an empire and became the Father of Europe

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Charlemagne, or Charles the Great, ruled over the vast Carolingian empire that spanned Europe during the Dark Ages. He became king of the Franks in A.D. 768 and conquered much of Europe during his 46-year reign.

During his life, he laid the foundations for the Holy Roman Empire, which would last nearly a millennium. He also established a new kind of royal leadership that would inspire generations of European kings.

"Charlemagne was a model for kings for centuries after his death, and his empire also provided the highest ideal of government into the nineteenth century," Michael Frassetto, an adjunct instructor of history at the University of Delaware, wrote in "Encyclopedia of Barbarian Europe: Society in Transformation" (ABC-CLIO, 2003).

Charlemagne championed religious reform and maintained a close relationship with the popes in Rome. Charlemagne also facilitated the Carolingian Renaissance, investing in the establishment of monasteries and cathedrals and fueling a renaissance of learning. As a result, scholarship and religion flourished both in his capital city, Aachen (in what is now Germany), and beyond. Nowadays, Charlemagne is remembered as the "Father of Europe" for uniting much of the continent under his rule.

Before Charlemagne

In the late fourth and early fifth century, the Roman Empire's influence in Western Europe collapsed as Germanic tribes swept through Rome, ultimately culminating in the fall of the Western Roman Empire in A.D. 476. From this power vacuum arose a series of Frankish tribes that had settled in Gaul (modern-day France), who consolidated their rule under a series of kings.

From these Frankish tribes emerged the Merovingian dynasty (mid 5th century - A.D. 751). But by the seventh century, the Merovingian kings held little power. The Frankish territories were very rarely united under one ruler and internal fighting was rampant.

Instead, mayors of the palace fulfilled a prime minister-type role and held the real power. Charles Martel, Charlemagne's grandfather, held this office and began to politically dominate both the Eastern and Western sides of the kingdom, beginning the slow takeover of the Merovingians by the nascent Carolingian dynasty, said early medieval historian Jennifer R. Davis, an associate professor of history at the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C..

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"It was Charlemagne's father who finally deposed the Merovingian dynasty and made himself king in 751, and Carolingian historiography in particular devoted a fair amount of energy to denigrating the Merovingians and justifying what basically was a coup," Davis told Live Science.

Pepin the Short, Charlemagne's father, claimed to have gained papal approval for deposing the Merovingians, although only Frankish sources attest to this, Davis said. In A.D. 753, however, both Frankish and papal sources noted that Pope Stephen II traveled to the Frankish states for the first time and formed an alliance. The pope declared that Frankish kings should be chosen only from the Carolingian line, and in return, the Franks would support the papacy’s territorial interests against pressure from the Lombards in Italy.

Who was Charlemagne?

Charlemagne was born to Pepin the Short and Bertrada of Laon around A.D. 742.

After Charlemagne's death in A.D. 814, the Frankish scholar Einhard, who was a contemporary of Charlemagne and had served in his court, wrote that little was known about Charlemagne's infancy or boyhood, in "Vita Karoli Magni," his biography of the king.

"Whatever his early education, it didn't include much reading or writing. "He never learned to write, so he could barely sign his documents — just with clumsy handwriting, but that was not his forte," Albrecht Classen, a professor of German studies at the University of Arizona, told Live Science.

Charlemagne inherited half of his father's kingdom upon Pepin the Short's death in A.D. 768, Einhard wrote. Charlemagne's brother Carloman inherited the Eastern half. The two Frankish kings had a fractious relationship.

"Many of Carloman's party kept trying to disturb their good understanding, and there were some even who plotted to involve them in a war with each other," Einhard wrote.

But in A.D. 771, Carloman's premature death saved the kingdom from civil war and gave Charlemagne dominion over all the Frankish territories, François L. Ganshof, a Belgian medieval historian, wrote in "Charlemagne" (Speculum, University of Chicago Press, 1949).

Expanding the Frankish kingdom

Almost immediately after his accession as king of the Franks, Charlemagne launched a campaign to secure his lands against neighboring forces that had been making continual attempts to infiltrate Frankish territory, according to Ganshof.

Charlemagne started a long and bloody war against the Saxons, another Germanic tribe that had harried Charlemagne's father. In A.D. 772, Charlemagne's forces marched into Saxony (modern northern Germany) and eventually established a permanent military presence in a fortified borderland.

Charlemagne used this expansion as an opportunity to spread Christianity to a traditionally pagan area of Europe, Ganshof wrote. Charlemagne's Christianization of the Saxons was a personal success for the emperor. During the decades-long war in Saxony, Charlemagne's military expansion continued across other areas of Europe. In 774, his conquest of the Lombards in northern Italy resulted in his coronation there. In 788, he conquered Bavaria, also absorbing it into his kingdom, according to Britannica.

To maintain order over such a huge territory, Charlemagne created a sophisticated administrative organization. Charlemagne also used the structures within the church to maintain control.

"The bishops or priests or deacons were not necessarily interested in secular power," Classen told Live Science. "But they were educated, and they were supported then by Charlemagne, who then had first-rate administrators all over his country."

But Charlemagne didn't hesitate to use violence against rebellious subjects. In his war with Saxony, he committed atrocities against those he was trying to conquer, most notably in 782 at the Massacre of Verden, where he is said to have ordered the killing of approximately 4,500 Saxons.

On the other hand, Charlemagne largely allowed the populations he conquered to function as they had done previously.

"He, on the whole, does not go through and try to take land away from the entirety of the existing aristocracy," Davis told Live Science. "If you revolt, yes; but otherwise, he kind of lets people be."

Becoming emperor of the Romans

Charlemagne's relationship with the church blossomed over his lifetime. Charlemagne established monasteries and cathedrals throughout his territories and, like his father before him, offered protection to the pope in return for the pope's continued patronage.

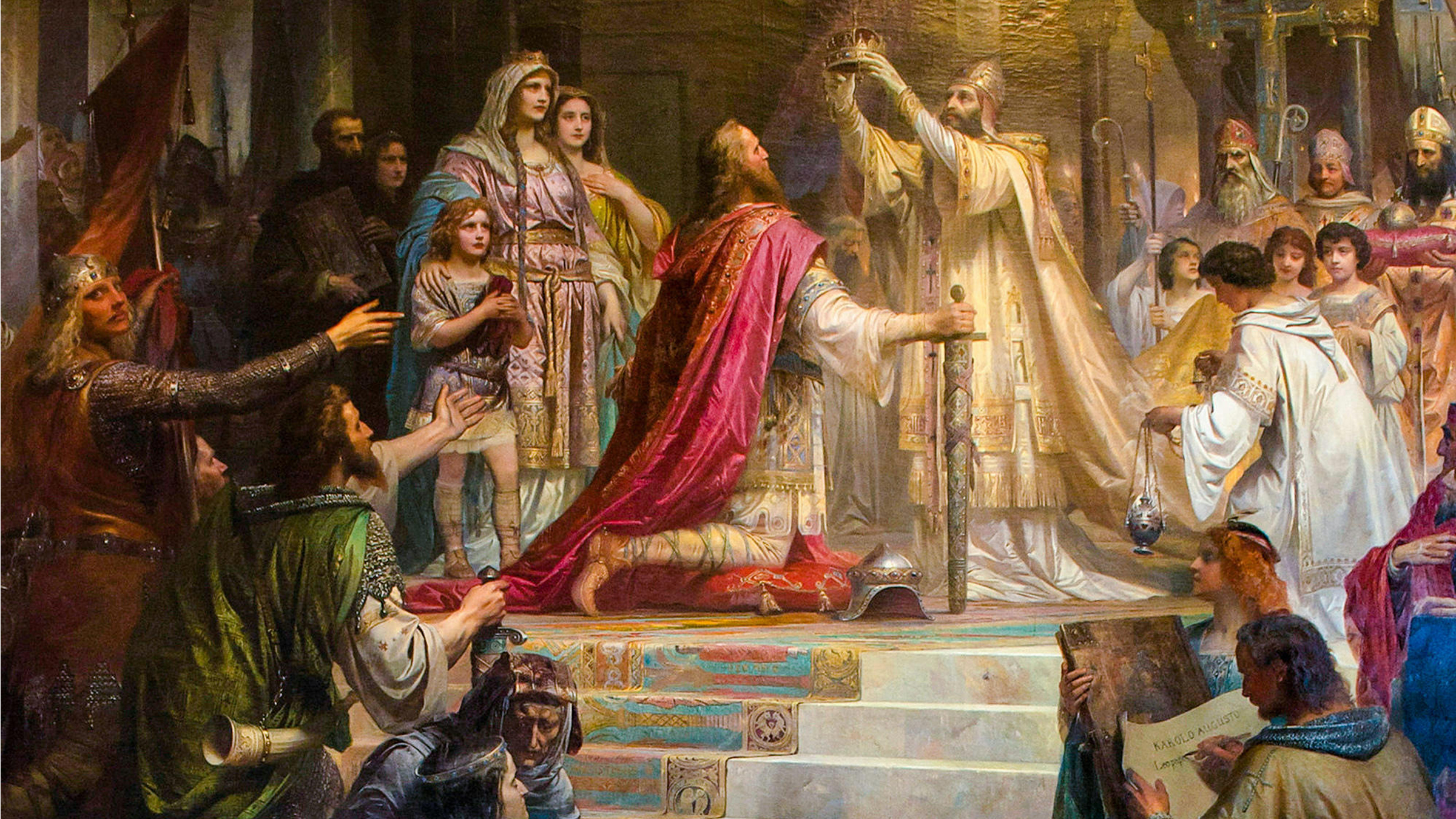

This symbiotic relationship led to Charlemagne being proclaimed emperor of the Romans, making him the first person to hold this title since the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

The coronation was said to be a result of Charlemagnes' intervention to save Pope Leo III. In 799, the pope fled to Charlemagne's court after being blinded in the street. Charlemagne arranged for the pope's safe return to Rome. In 800, Charlemagne traveled to Rome and organized for Pope Leo III to publicly swear an oath to eradicate the charges of misconduct levied against him by his opponents.

On Christmas Day A.D. 800, Pope Leo III thanked Charlemagne by anointing him emperor — an honor Charlemagne had probably been angling for, Marios Costambeys, a medieval historian at the University of Liverpool in England, told Live Science. "Almost nobody believes what his biographer says, which is that when he goes to Rome and is crowned, this is a complete surprise to him and that he didn't expect it," he said. "There are lots of signs that, in fact, this was all being set up for a couple of years beforehand."

Charlemagne was crowned emperor, but in the intervening centuries, that title would evolve into Leader of the Holy Roman Empire, which did not exist during Charlemagne's time. Once crowned, Charlemagne became the first non-Roman emperor in Europe, appointed by the pope and thus God, which helped to consolidate Charlemagne's authority throughout his empire.

Charlemagne and the Carolingian Renaissance

Charlemagne's reign ushered in the Carolingian Renaissance. Charlemagne set up religious schools across Europe.

"He called in the first major school master, Alcuin of York," Classen said. "Once that school had graduated some students, they became abbots. They set up their own monasteries, and each monastery had its own school. Out of those schools came new abbots for other churches. So it spread all over the country."

Art, architecture and literature inspired by fourth-century Roman culture flourished throughout the Carolingian Empire, even though the emperor was illiterate, Classen said.

The Renaissance, or "correctio" as the Carolingians referred to it, also helped Charlemagne promote Christian scholarship and culture. His investment in monastic schools and the production of manuscripts and documents allowed for wider access to biblical and liturgical knowledge, Costambeys said.

What is Charlemagne's legacy?

Charlemagne died in A.D. 814 at age 72 and left his throne to his son, Louis the Pious, who had been acting as co-emperor when his father's health had declined in the later years of his life. After his death, Charlemagne was elevated to a legendary status and mythologized as the perfect example of kingship, much like the mythical King Arthur in England.

The Frankish king also inspired future leaders, such as Napoleon Bonaparte, who saw Charlemagne's reign as an ideal example of imperialism. Charlemagne "very quickly becomes a model," Costambeys said. "He's the reference point for rulership in Europe, certainly Latin Christian Europe, for over a thousand years after," said Costambeys.

The Holy Roman Empire, which evolved from Charlemagne's Carolingian Empire, continued to exist under a series of emperors until 1806, almost a millennium after Charlemagne's death.

Emily is the Staff Writer at All About History magazine, writing and researching for the magazine's content. She has a Bachelor of Arts degree in History from the University of York and a Master of Arts degree in Journalism from the University of Sheffield. Her historical interests include Early Modern and Renaissance Europe, and the history of popular culture.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus