Skull of bear held captive to fight Roman gladiators discovered near ancient amphitheater in Serbia

Archaeologists determined that the bear had an infected injury and had been held captive for a significant amount of time.

The battered skull of a brown bear discovered near a Roman amphitheater in Serbia reveals that the wild animal had been kept in captivity for years and was fighting off an infection when it died around 1,700 years ago.

The finding is the first direct evidence of the use of bears in the gladiatorial arena and attests to the barbarism of animal spectacles in the Roman Empire.

"We cannot say with certainty whether the bear died directly in the arena, but the evidence suggests the trauma occurred during spectacles and the subsequent infection likely contributed significantly to its death," study lead author Nemanja Marković, a senior research associate at the Institute of Archaeology in Belgrade, told Live Science in an email.

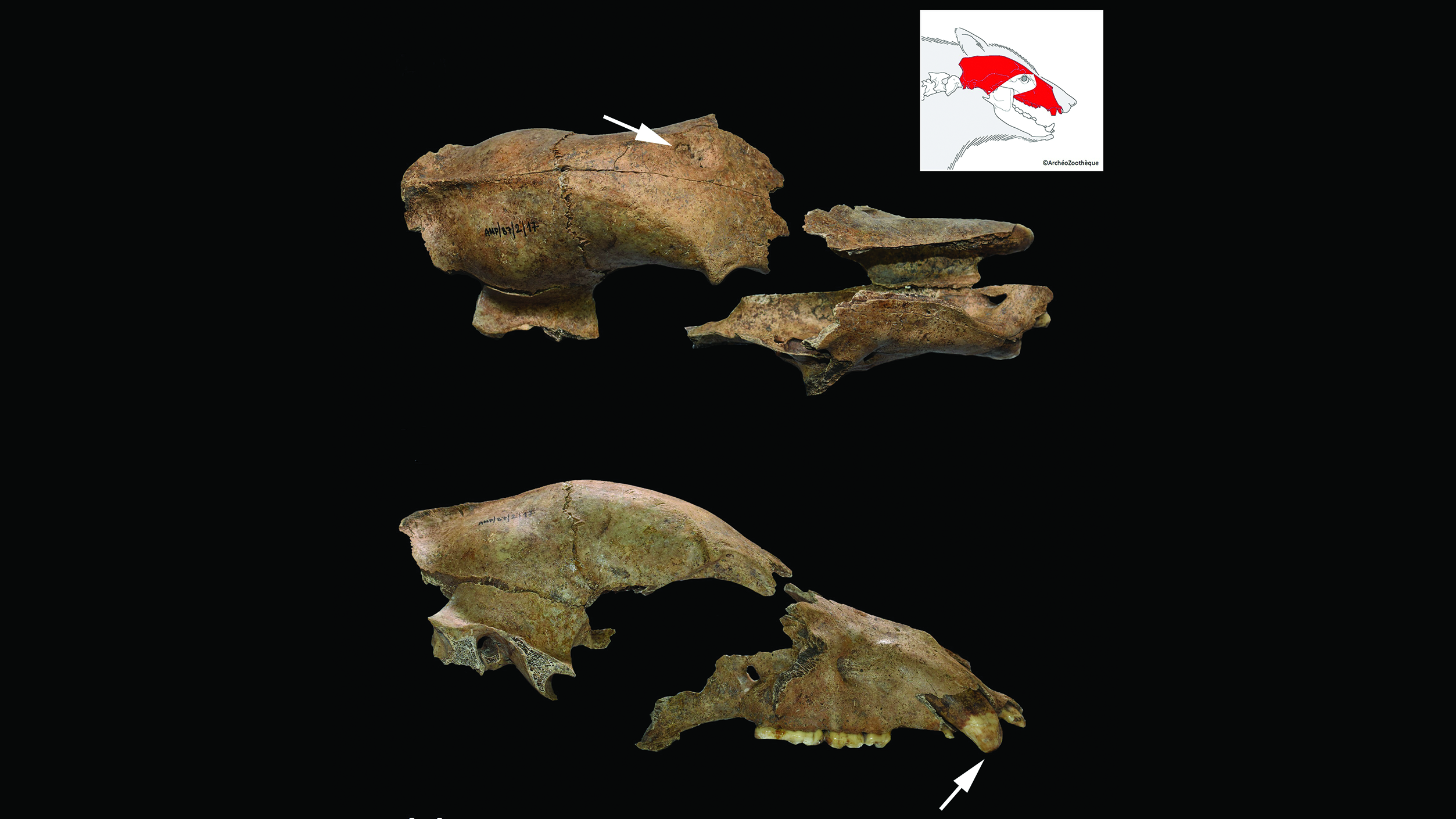

In a study published Monday (Sept. 1) in the journal Antiquity, Marković and colleagues detailed their analysis of the fragmented skull of a brown bear (Ursus arctos) excavated in 2016 near the amphitheater at Viminacium, a Roman frontier military base in present-day Serbia.

The amphitheater at Viminacium was built in the second century A.D. Oval-shaped with high walls, it could seat about 7,000 people. Archaeologists recovered the bear skull near the entrance to the amphitheater, along with a number of other animal bones, including those of a leopard, the researchers noted in the study.

"Previous research suggests animals killed in the arena were butchered nearby, their meat distributed, and bones discarded close to the amphitheatre — not buried in a formal animal graveyard," Marković said.

Bears forced to participate in these ancient spectacles had a variety of roles. They could be made to fight "venatores," gladiators who specialized in hunting; to brawl with other animals; to execute convicts; or to give trained performances.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Related: Lion mauled gladiator to death 1,800 years ago in Roman Britain, controversial study suggests

The researchers' analysis of the brown bear skull revealed just how brutal these spectacles were for the animals.

Using ancient DNA analysis, the researchers determined that the bear was male and was from the local area, and his teeth suggested he was about 6 years old when he died. Carbon dating of animal bones from the area where the bear was found gave a date range of A.D. 240 to 350, a time when the Viminacium amphitheater was regularly hosting gladiatorial games.

A large lesion on the front of the bear's skull showed signs of healing but also signs of infection, suggesting he was struggling with the injury at death. This traumatic injury could have been inflicted by a "venator" equipped with a spear, the researchers wrote in the study.

The animal's jaws also showed evidence of infection, and the researchers identified abnormal wear on his canine teeth. Captive bears are known to chew on the bars of their cages, the researchers noted, which can lead to the kinds of dental and jaw problems seen in this ancient bear.

"This bear was likely kept in captivity for years, not just weeks," Marković said, in which case he would have featured repeatedly in Roman spectacles at Viminacium.

Although historical records mention the use of brown bears in gladiatorial spectacles, "this study provides the first direct osteological evidence for the participation of brown bears in Roman spectacles," the researchers concluded, and offers a glimpse into the use and treatment of animals in the Roman Empire.

Roman emperor quiz: Test your knowledge on the rulers of the ancient empire

Kristina Killgrove is a staff writer at Live Science with a focus on archaeology and paleoanthropology news. Her articles have also appeared in venues such as Forbes, Smithsonian, and Mental Floss. Kristina holds a Ph.D. in biological anthropology and an M.A. in classical archaeology from the University of North Carolina, as well as a B.A. in Latin from the University of Virginia, and she was formerly a university professor and researcher. She has received awards from the Society for American Archaeology and the American Anthropological Association for her science writing.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus