Only part of rare 280 million-year-old fossil is real — the rest is mostly paint

Researchers have found that a fossil of the lizard-like Tridentinosaurus antiquus is mostly fake.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A rare 280 million-year-old fossil resembling a lizard-like creature is mostly just a carved rock painted black, a new analysis reveals.

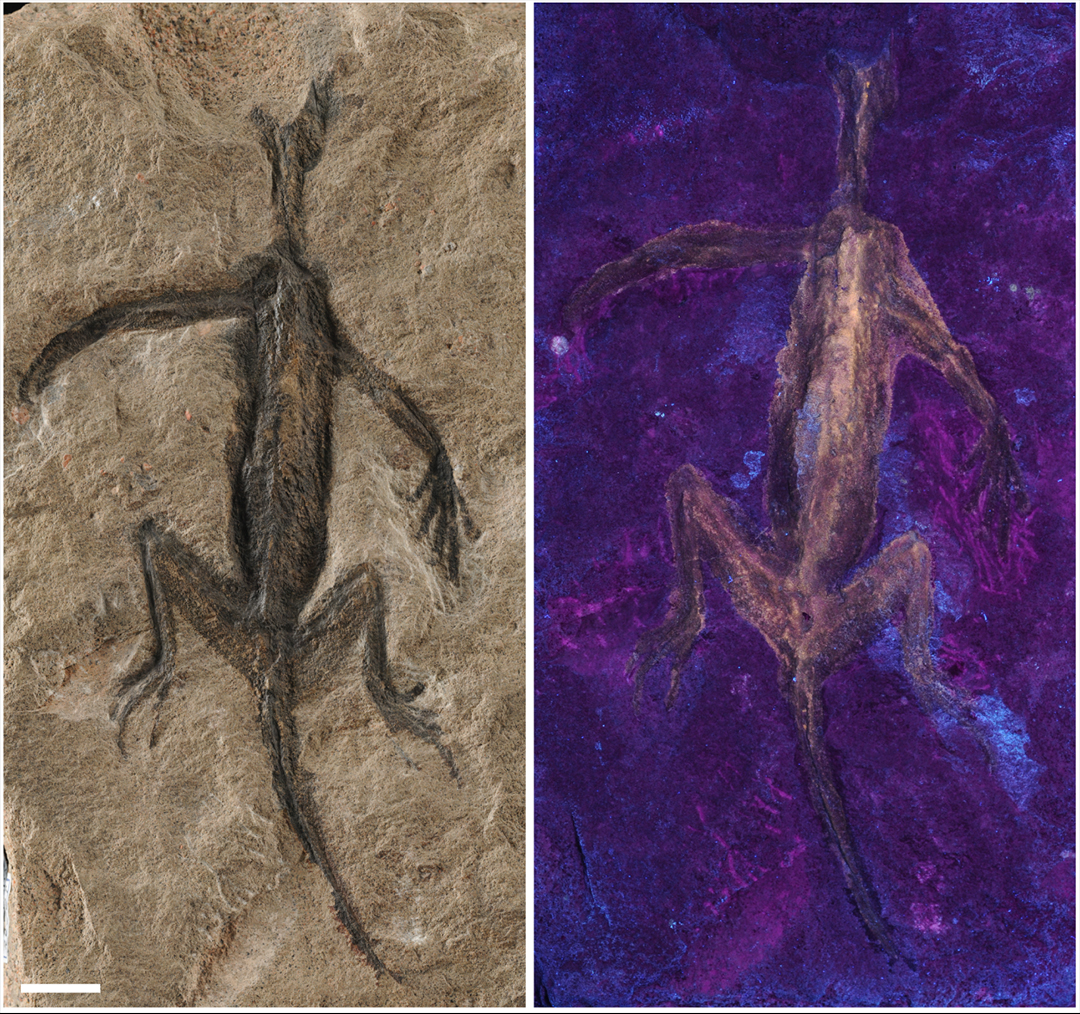

The Permian fossil, discovered in the Italian Alps in 1931 and named Tridentinosaurus antiquus, is shaped like a lizard and has a dark coloration, which researchers thought was preserved skin. However, in actuality, most of its body is human-made, according to a new study published Feb. 15 in the journal Palaeontology.

Researchers made the discovery when they reexamined the fossil with modern techniques, including 3D modeling, ultraviolet (UV) photography, high-powered microscopes and chemical analysis.

The study's lead author, Valentina Rossi, a paleobiologist at University College Cork in Ireland, told Live Science she was hoping to learn more about how the creature was fossilized and discovering the skin was fake was "totally unexpected."

"We analyzed many samples from various parts of the body of the animal, so we are certain that, unfortunately, there is no trace of original soft tissue preserved," she said.

The entire fossil isn't fake, though; genuine hind-limb bones and tiny bone scales are preserved in the rock. Therefore, the additional carving and paint may have been poor fossil preparation in years past, rather than an outright forgery like the Piltdown Man or other scientific hoaxes.

Related: 120 million-year-old 'plants' turn out to be ultra-rare fossilized baby turtles

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Most of the Permian period (299 million to 252 million years ago) fossils from the Alps are animal tracks rather than bones, so the discovery of a fossil like T. antiquus was a significant find in the early 1930s. Paleontologist Piero Leonardi studied and described the specimen in 1959, concluding that the fossil's dark outline represented exceptional tissue preservation.

"He couldn't analyze this fossil with the techniques that we have today, so his description was the best we [scientists] could make at the time," Rossi said.

Rossi and her team used various techniques to tease the truth out of the ancient rock. Unlike organic fossilized material, the fossil shined yellow under UV light, revealing that it had some kind of coating. The researchers hoped to find soft tissue beneath this coating, but there was nothing but the manufactured pigment "bone black," which is made from charred animal bones and used in paint.

"We were all a bit sad because, of course, the tone of the story changed completely," Rossi said.

Rossi doesn't believe whoever prepared the fossil was trying to create a fake creature. They may have discovered the hind limbs and carved the shape of a lizard where they thought the rest of the animal would be.

"It's almost like this person has seen the legs exposed and then thought, 'OK, well, if those are the hind limbs of a lizard, if I go this way, I should find something else,'" Rossi said.

The researchers also found bony scales, called osteoderms, like those found on crocodiles, which could have further inspired whoever carved it to finish the lizard outline. "Maybe the black paint at that point was just to make it more visible," Rossi added.

The new study leaves many open questions, including the creature's identity. T. antiquus' bones are poorly preserved and lack diagnostic features that would allow researchers to compare it with other species. However, the presence of osteoderms leads Rossi and her team to believe it was a reptile-like animal of some kind.

"Our money is still on a reptile-looking creature," Rossi said.

Patrick Pester is the trending news writer at Live Science. His work has appeared on other science websites, such as BBC Science Focus and Scientific American. Patrick retrained as a journalist after spending his early career working in zoos and wildlife conservation. He was awarded the Master's Excellence Scholarship to study at Cardiff University where he completed a master's degree in international journalism. He also has a second master's degree in biodiversity, evolution and conservation in action from Middlesex University London. When he isn't writing news, Patrick investigates the sale of human remains.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus