Dinosaur-age sea monster with 'face full of huge, dagger-shaped teeth' discovered in Moroccan mine

Extinct marine lizard the size of an orca with sharp teeth and a strong jaw was a top predator during the dinosaur age.

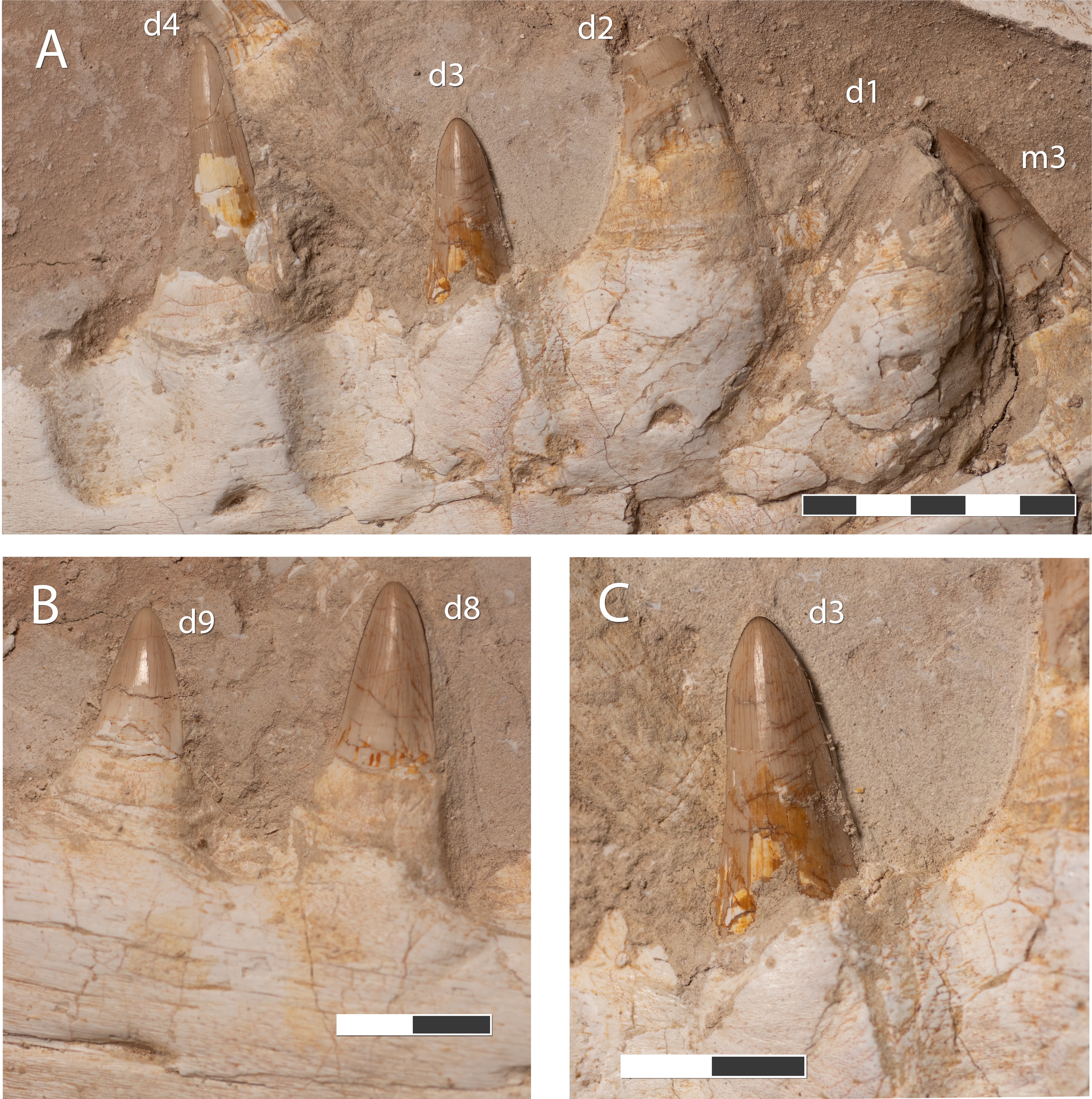

Paleontologists in Morocco have discovered the fossilized remains of a huge, never-before-seen species of marine lizard with "dagger-like" teeth.

The reptile was around 26 feet (8 meters) long — about the same length as an orca — and hunted in the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of what is now Africa at the end of the dinosaur age, about 66 million years ago, according to a study published March 1 in the journal Cretaceous Research.

The creature is named Khinjaria acuta, which is derived from khinjar, the Arabic word for "dagger," and acuta, which means "sharp" in Latin. Its formidable jaws would've enabled it to feast on very large prey, including sharks and other marine reptiles.

The "nightmarish" reptile was a member of the Mosasauridae family, also known as mosasaurs — an extinct group of marine lizards whose relatives today include Komodo dragons (Varanus komodoensis) and anacondas, according to a statement from the University of Bath in England.

Its fearsome teeth and jaws can be seen in the skull and partial skeleton that were found buried inside a phosphate mine near Morocco's port city of Casablanca.

Analysis of the skull and jaw suggests the creature had "a terrible biting force," study co-author Nour-Eddine Jalil, a professor and collection manager at the National Museum of Natural History in Paris, said in the statement.

Related: 94 million-year-old fossilized sea monster is the oldest of its kind in North America

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Khinjaria was just one of many top predators prowling the ocean for prey during the Cretaceous period (145 million to 66 million years ago).

"This was an incredibly dangerous time to be a fish, a sea turtle or even a marine reptile," lead study author Nick Longrich, a senior lecturer in the Department of Life Sciences and the Milner Centre for Evolution at the University of Bath, said in the statement.

The discovery of Khinjaria adds to the huge number of known top marine predators at the end of the Cretaceous — raising the question of how and why so many mosasaurs appeared at this time.

"We have multiple species growing larger than a great white shark, and they're top predators, but they all have different teeth, suggesting they're hunting in different ways," Longrich said.

"This is one of the most diverse marine faunas seen anywhere, at any time in history, and it existed just before the marine reptiles and the dinosaurs went extinct," he added. "Some mosasaurs had teeth to pierce prey, others to cut, tear, or crush. Now we have Khinjaria, with a short face full of huge, dagger-shaped teeth."

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.