'Killer' Cretaceous croc devoured a dinosaur as its last meal

The ancient reptile fossilized with a full belly.

About 95 million years ago in what is now Australia, a massive crocodile relative clamped down with its powerful jaws on the small body of a dinosaur and gulped nearly all of it down in one mighty swallow. The crocodilian died soon after, and as it fossilized, so did the partly-digested and near-complete dinosaur in its belly.

The wee dinosaur was a young ornithopod — a mostly bipedal herbivore group that includes duck-billed dinosaurs. These are the first bones of an ornithopod to be found in this part of the continent, and the animal may be a previously unknown species.

Scientists recently discovered the remains of the ancient croc predator — and its well-preserved last meal — in the Great Australian Super Basin, at a site dating to the Cretaceous period (about 145.5 million to 65.5 million years ago). Though the croc fossil was missing its tail, hind limbs and much of its pelvis, its skull and many bones from the rest of its body were intact; it measured over 8 feet (2.5 meters) long when it died and would likely have grown even more massive had it lived, the researchers reported in a new study.

Related: Crocs: Ancient predators in a modern world (photos)

They dubbed the crocodile relative Confractosuchus sauroktonos (kon-frak-toh-SOO'-kus saw-rock-TOH'-nus), which is a mouthful (much like the dinosaur that the giant crocodilian swallowed almost whole), but that's because it includes a lot of information about the fossil. The cumbersome name — a new genus and species — translates from words in Latin and Greek that collectively mean "broken crocodile dinosaur-killer," according to the study. "Dinosaur-killer" came from the fossil's gut contents, while "broken" refers to the stony matrix surrounding the fossil, which shattered during excavation in 2010 and revealed smaller bones inside the croc's abdomen, according to a statement released by the Australian Age of Dinosaurs Museum in Winton, Queensland.

Crocodilians first coexisted with dinosaurs beginning in the Triassic period (251.9 million to 201.3 million years ago), and prior evidence suggests that they found some dinosaurs to be delicious. Tooth marks on fossilized dinosaur bones (and in one case, a tooth embedded in bone) hint that some crocodilians dined on dinosaurs, either hunting them or scavenging their remains. But paleontologists rarely find preserved gut contents in crocodilians, perhaps because their guts contained powerfully corrosive acids, as do those of modern crocodiles. This new find provides the first definitive evidence showing that dinosaurs were eaten by giant Cretaceous crocs, the scientists reported Feb. 10 in the journal Gondwana Research.

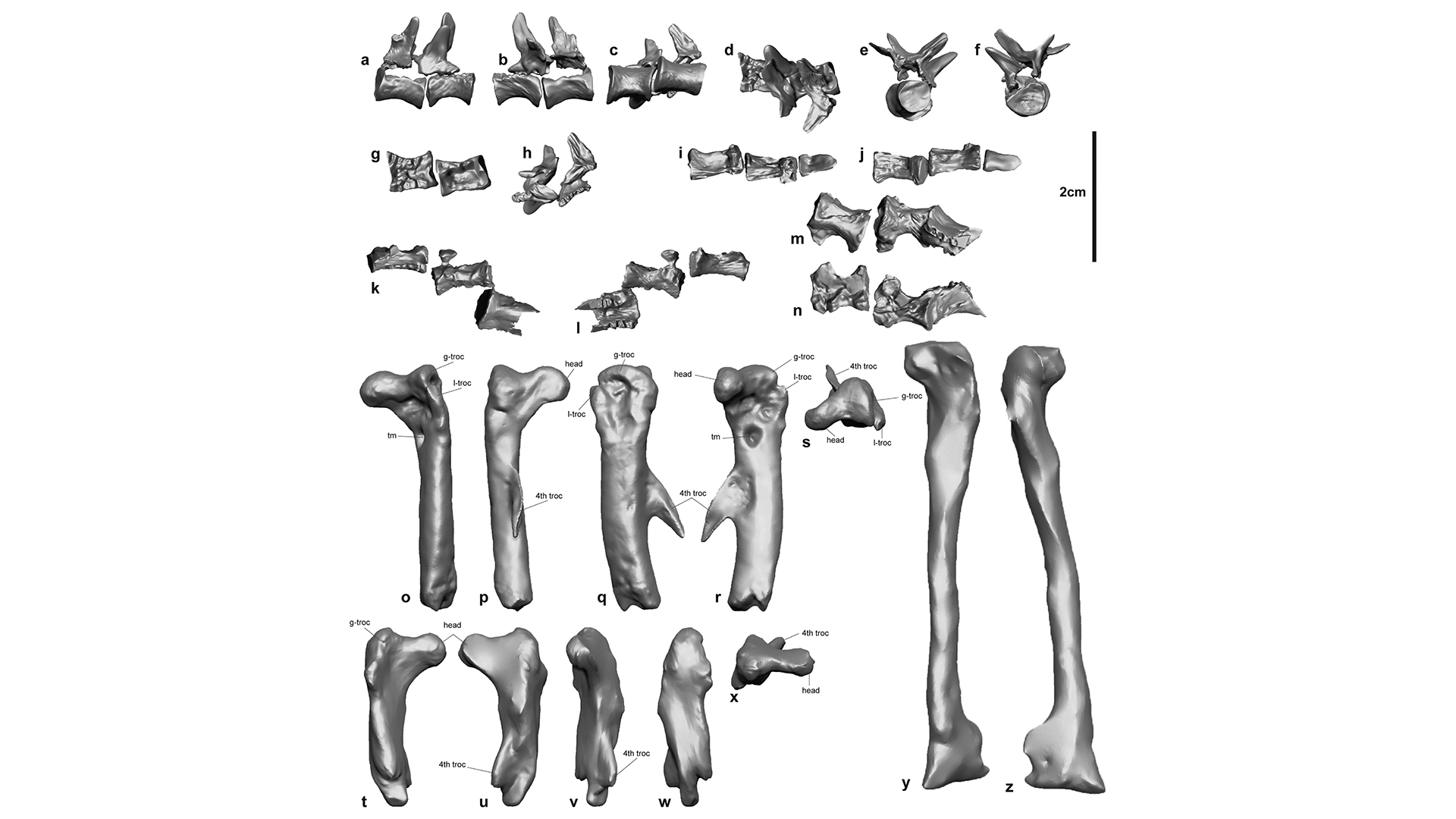

Because the small dinosaur's bones were too fragile to remove from the rock around them, the researchers scanned the croc's abdomen with X-ray computed tomography (CT) devices and then created digital 3D models of the delicate bones. They calculated that the ornithopod weighed nearly 4 pounds (1.7 kilograms). Most of the dinosaur's skeleton was still connected after it was swallowed, but as the dinosaur-killer munched its meal, it bit down so hard that it broke one of the ornithopod's femurs in half, and it left a tooth embedded in the other femur, the researchers reported.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

While the croc's stomach contents show that its last meal was a small dinosaur, the predator likely snapped up other Cretaceous animals, too. However, dinosaurs were probably a regular part of their diet, according to the study.

"It is likely dinosaurs constituted an important resource in the Cretaceous ecological food web," lead study author Matt White, a research associate at the Australian Age of Dinosaurs Museum, said in the statement. "Given the lack of comparable global specimens, this prehistoric crocodile and its last meal will continue to provide clues to the relationships and behaviours of animals that inhabited Australia millions of years ago."

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus