Africa Is Splitting in Two, and Here's the Proof

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A piece of East Africa is expected to break off the main continent in tens of millions of years. And if you need any proof, look no further than Kenya's Rift Valley, where a giant, gaping tear opened up following heavy rains and seismic activity, according to Face2Face Africa.

The enormous crack appeared on March 19 and measures more than 50 feet (15 meters) wide and several miles along, Face2Face Africa and other news sources reported. Moreover, it's still growing longer.

The rift is likely a sign of things to come as the plate tectonics under Africa rearrange themselves. The majority of Africa sits on top of the African Plate. However, a long, vertical piece of eastern Africa lies on top of the Somali Plate. This juncture where the two plates meet is known as the East African Rift, which stretches an astonishing 1,800 miles (3,000 kilometers), or about the distance from Denver to Boston. [50 Interesting Facts About Planet Earth]

To avoid confusion (given that Africa doesn't sit on only one plate), researchers call the giant African plate the Nubian Plate. In essence, the Nubian and Somali plates are being split in two, according to a piece in The Conversation by Lucia Perez Diaz, a postdoctoral researcher at the Fault Dynamics Research Group at Royal Holloway, University of London.

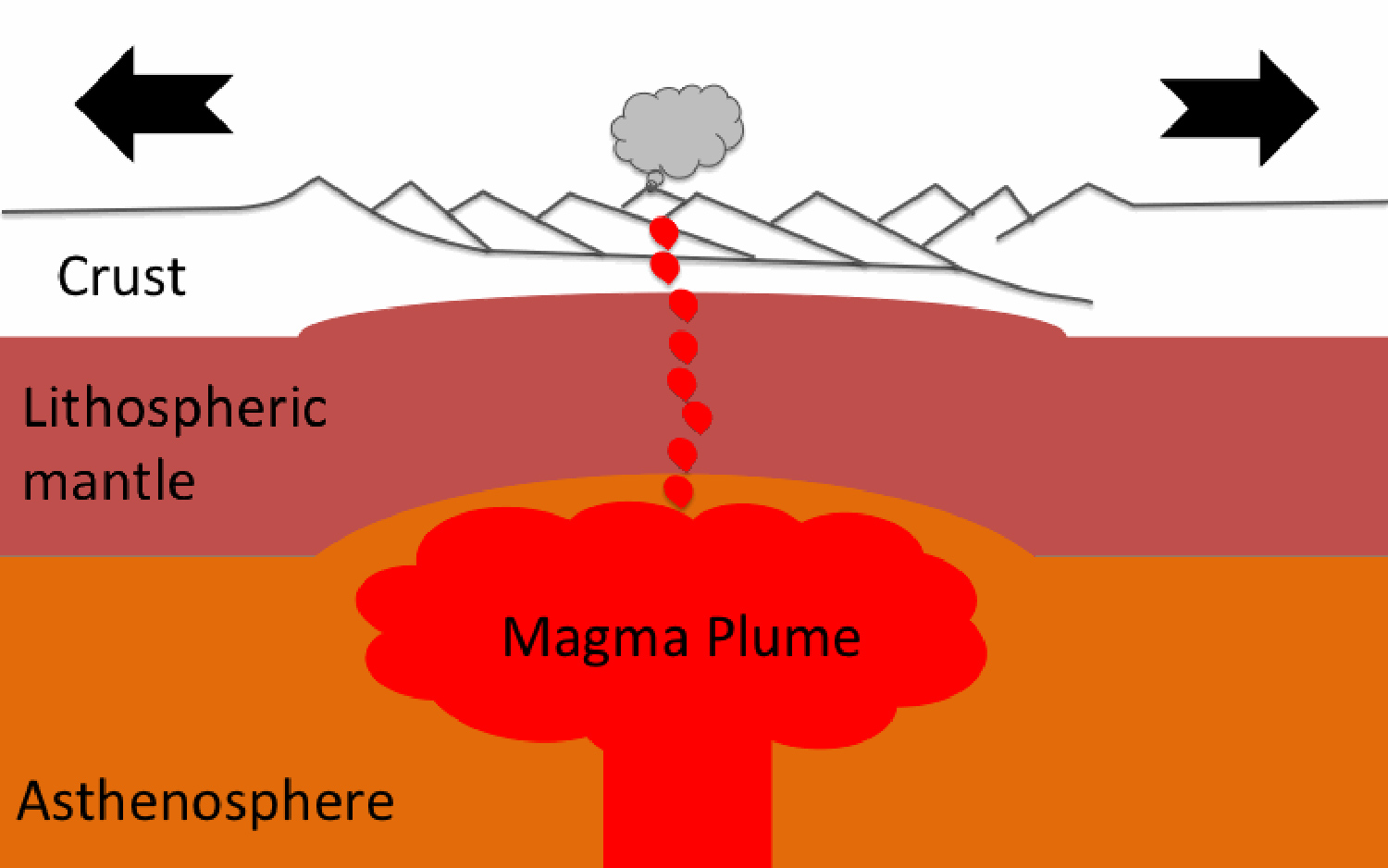

Here's how two plates split apart: The lithosphere, which is broken up into tectonic plates, is made of the Earth's crust and the upper part of the mantle. When the lithosphere experiences tugging forces, it becomes thinner, until it eventually ruptures, Perez Diaz wrote. This rupture has already led to the formation of the rift valley.

The rupture process is often accompanied by seismic activity and volcanism. In the East African Rift's case, a large mantle plume under the lithosphere is weakening it, allowing it to stretch, Perez Diaz said.

Rifts lead to recognizable land formations — that is, a series of depressions surrounded by higher ground. The East African Rift has a series of rift valleys that can be seen from space. However, not all of these rifts formed at the same time. Rather, they started in northern Ethiopia about 30 million years ago and spread southward toward Zimbabwe at an average rate of between 1 and 2 inches (2.5 and 5 centimeters) a year, Perez Diaz said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As the Somali and Nubian plates move apart, the region can experience earthquakes, as it did in southwestern Kenya last week. The giant crack tore the busy Mai Mahiu-Narok road in two and split apart houses, including the home of a 72-year-old woman who was eating dinner with her family when it happened, according to Face2Face Africa.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus