Nipples 'Light Up' Brain the Way Genitals Do

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

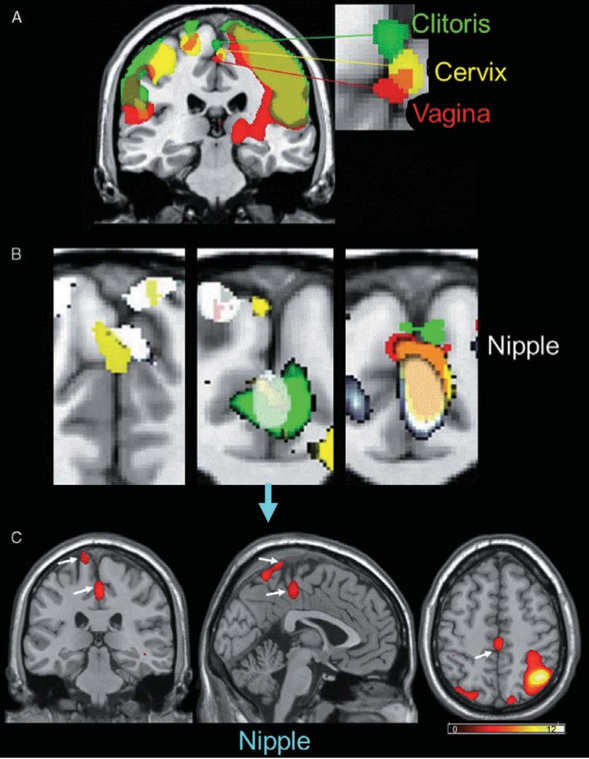

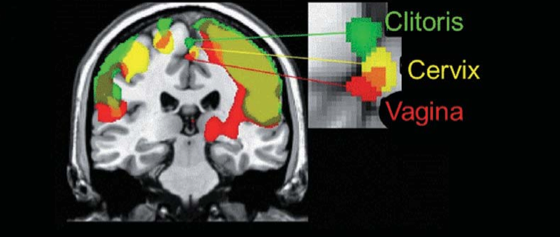

For many women, nipples are erogenous zones. A new study may explain why: The sensation from the nipples travels to the same part of the brain as sensations from the vagina, clitoris and cervix.

The study, published online July 28 in the Journal of Sexual Medicine, is the first to map the female genitals onto the sensory portion of the brain. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), researchers noted which brain areas become active when women touch various parts of their bodies. The genital-sensing brain areas in women roughly correspond to the same areas in men, but the nipple finding was a surprise, said study researcher Barry Komisaruk, a psychologist at Rutgers University.

"My speculation is that this could be the basis for many women saying that nipple stimulation is erotogenic, because it stimulates the same area as the genitals," Komisaruk told LiveScience.

Sexy stimulation

Four major nerves bring signals from women's genitals to their brains, Komisaruk said. The pudendal nerve connects the clitoris, the pelvic nerve carries signals from the vagina, the hypogastric nerve connects with the cervix and uterus, and the vagus nerve travels from the cervix and uterus without passing through the spinal cord (making it possible for some women to achieve orgasm even though they have had complete spinal cord injuries).

Experimenters had mapped the male genital senses onto an area of the brain called the medial paracentral lobule, which sits in the crevice between the two brain hemispheres. (If you imagine wearing earmuffs, the medial paracentral lobule would be on the top of your head, right under the band of the earmuffs.) What was missing, Komisaruk said, was a study tracing those four nerves to where in the brain they send their signals. [Read Inside the Brain: A Journey Through Time]

For their study the researchers recruited 11 healthy, non-pregnant women ages 23 to 56. While inside the brain scanner, each woman stimulated her clitoris, vagina, cervix and nipple by tapping rhythmically with a finger or, in the case of the vagina and cervix, using a plastic dildo.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Nipple mystery

The resulting brain images showed a nexus of activation in the medial paracentral lobule, just as in men. Each area of the genitals showed up in its own spot within this brain region, Komisaruk said. [See the brain images ]

"Even though they're all clustered there like a cluster of grapes, the response to each [genital area] is different," he said. "They overlap, but they're separable."

Nipple stimulation showed up in the area of the brain that receives chest sensations, but it also popped up alongside the genital sensations in the medial paracentral lobule, the researchers found. There could be two reasons for this, Komisaruk said. One is indirect: Stimulating the nipples, as in breast-feeding, releases the hormone oxytocin. This hormone, which is also released during labor, triggers uterus contractions. So it's possible, Komisaruk said, that nipple stimulation triggers uterine contractions, which then produce a sensation in the genital area of the brain.

However, preliminary data suggest that nipple nerves may directly link up with the brain, skipping the uterine middleman. A few men who have been studied show the same pattern of nipple stimulation activating genital brain regions, Komisaruk said. One of his graduate students is further testing the idea by studying the response of women who have had a hysterectomy, meaning their uterus has been removed.

The erotic brain

The women in the study (each of whom was paid $100 to participate) were not necessarily turned on by the self-stimulation in the fMRI scanner; even so, using a similar setup in an earlier study, Komisaruk and his colleagues were the first to locate the female orgasm in the brain.

That leaves the question of what makes a sensation erotic, Komisaruk said.

"Are there particular brain regions that have to be activated in order for genital stimulation to be converted from run-of-the-mill stimulation versus stimulation with an erotic quality?" he said. "That is the big question."

For the record, while eroticism is a mystery, Komisaruk and his lab team found that an orgasm involves a variety of brain regions, including the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus; amygdala; accumbens-bed nucleus of the stria terminalis-preoptic area; hippocampus; basal ganglia; cerebellum; the anterior cingulate, insular, parietal and frontal cortices; and the lower brainstem. [10 Things Every Man Should Know About a Woman's Brain]

Komisaruk hopes his research will help people who can't reach orgasm. More broadly, he wants to find out if people can learn to control their brain activity directly, much as we take for granted our ability to move our fingers and toes.

"If we can control a part of the brain that produces pleasurable sensation, what would that do in the case of, say, depression or anxiety or addiction or obesity?" Komisaruk said. "We really don't know what the limits are as far as what we can make our brains do."

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus