Big Quakes Weaken Faults on Other Side of Earth

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Massive earthquakes on one side of the globe can weaken faults half a world away, scientists announced today.

A group of seismologists studying the massive 2004 earthquake that triggered killer tsunamis throughout the Indian Ocean found that the quake had weakened at least a portion of California's famed San Andreas Fault.

The finding, detailed in the Oct. 1 issue of the journal Nature, suggests Earth's largest earthquakes can weaken fault zones worldwide and trigger periods of increased global seismic activity.

The announcement of the new link comes just one day after two different earthquakes rattled the Samoan Islands and Indonesia, the former generating a tsunami that has killed scores of people. Scientists aren't sure if these two temblors were related, but they said it is possible.

Suspected link

Scientists began suspecting a global quake linkage after the devastating 2004 earthquake, an estimated 9.3-magnitude temblor.

"An unusually high number of magnitude 8 earthquakes occurred worldwide in 2005 and 2006," said study co-author Fenglin Niu of Rice University. "There has been speculation that these were somehow triggered by the Sumatran-Andaman earthquake that occurred on Dec. 26, 2004, but this is the first direct evidence that the quake could change fault strength of a fault remotely."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

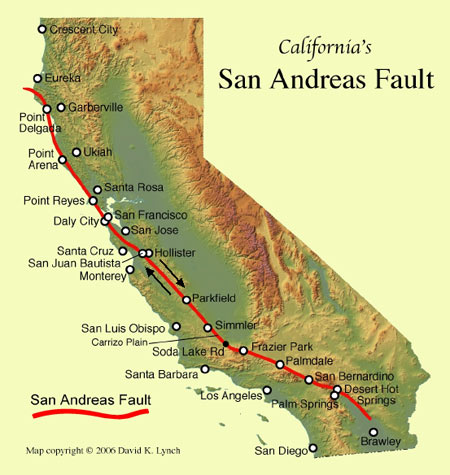

Niu and co-authors Taka'aki Taira and Paul Silver, both of the Carnegie Institution of Science in Washington, D.C., and Robert Nadeau of the University of California, Berkeley, examined more than 20 years of seismic records from Parkfield, Calif., which sits astride the San Andreas Fault in Southern California.

The team zeroed in on a set of repeating microearthquakes that occurred near Parkfield over two decades. Each of these tiny quakes originated in almost exactly the same location.

By closely comparing seismic readings from these quakes, the team was able to determine the "fault strength" — the shear stress level required to cause the fault to slip — at Parkfield between 1987 and 2008.

Three fault changes

The team found fault strength changed markedly at three times during the 20-year period.

The authors surmised that the 1992 Landers earthquake, a magnitude 7 quake north of Palm Springs, Calif. — about 200 miles from Parkfield — caused the first of these changes. The study found the Landers quake destabilized the fault near Parkfield, causing a series of magnitude 4 quakes and a notable "aseismic" event — a movement of the fault that played out over several months — in 1993.

The second change in fault strength occurred in conjunction with a magnitude 6 event at Parkfield in September 2004.

The team found another change at Parkfield later that year that could not be accounted for by the September quake alone. Eventually, they were able to narrow the onset of this third shift to a five-day window in late December during which the Sumatran quake occurred.

"The long-range influence of the 2004 Sumatran-Andaman earthquake on this patch of the San Andreas suggests that the quake may have affected other faults, bringing a significant fraction of them closer to failure," Taira said.

The research was supported by the National Science Foundation, the Carnegie Institution of Washington, the University of California, Berkeley, and the U.S. Geological Survey.

- Video: Earthquake Forecast

- Earthquake News, Images and Information

- The Big Earthquake Quiz

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus