How Bird Flu Infects Humans and Why We Don't Spread It

More than 100 people have died from infection with the avian flu virus, but so far it can't hop from person to person. That's why there has been no global outbreak among humans.

Scientists are not quite sure why the virus, called H5N1, has yet to morph into a strain that can be transmitted between humans. One study found that the avian strain can't bind to human cells. Another study, released last week, suggested one key mutation is all that is keeping the avian flu out of the human population.

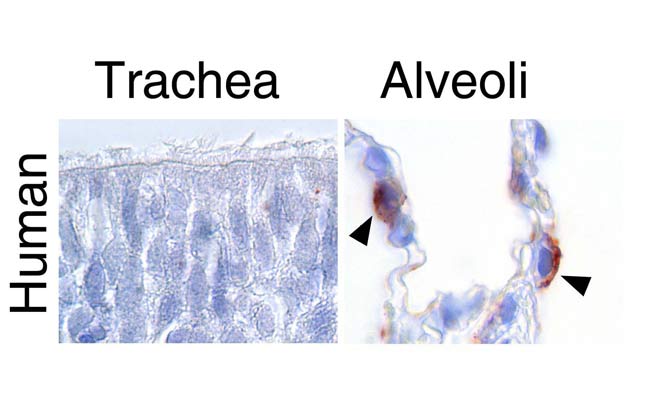

Now two independent research teams have revealed that bird flu virus can bind to human lung cells, but it attaches too deep in the respiratory tract to be coughed up and spread.

One of the teams also found that infection could lead to increased risk of viral pneumonia.

The two studies, both announced today, are detailed in the March 22 issue of the journal Nature and the March 23 issue of Science.

Influenza most commonly spreads in liquid droplets made airborne by coughing or sneezing. You can also be infected by touching surfaces where droplets have landed—such as countertops or doorknobs—and then touching your mouth or rubbing your eyes.

Influenza viruses, of which there are many strains that evolve constantly, require access to host cells in order to reproduce and spread. To gain access, surface molecules on the virus must match receptors on the surface of the potential host's cells.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The new research reveals that cells with H5N1 avian flu receptors are prevalent deep in the lungs of people who have died from infection, usually after direct contact with infected birds. The virus can readily enter and replicate within lung cells called type II pneumocytes. These cells are important for repairing lung tissue and producing molecules necessary for normal lung function.

"But these receptors are rare in the upper portion of the respiratory system," said University of Wisconsin-Madison research Yoshiro Kawaoka, who led the study in Nature. "For the viruses to be transmitted efficiently, they have to multiply in the upper portion of the respiratory system so that they can be transmitted by coughing and sneezing."

To do this, the bird flu viruses must undergo further genetic alterations and borrow cell surface receptors from a human influenza strain. For these gene swaps to occur, a bird or human (or intermediary host such as a pig) must be infected with both the avian H5N1 and a human influenza strain, researchers say. That way, the two strains can share genetic material to make a new variety.

"No one knows whether the virus will evolve into a pandemic strain, but flu viruses constantly change," Kawaoka said. "Certainly, multiple mutations need to be accumulated for the H5N1 virus to become a pandemic strain."

Although millions of poultry in Asia have been infected with the H5N1 virus, there have been fewer than 200 confirmed human infections.

"However, in the rare cases that human infection has occurred, the fatality rate is high, and the primary lesion is pneumonia," Science study co-author Thijs Kuiken of the Erasmus Medical Center in the Netherlands told LiveScience.

Pneumonia is an infection or inflammation of the lungs. It can be caused by bacteria, viruses, fungi, and other microorganisms. Because the H5N1 virus targets cells responsible for repairing damage to the lung lining, seeping wounds are slow to heal.

Viral pneumonia is generally not very serious to healthy adults, but it can be deadly for very young and very old patients as well as those with impaired immune systems.

The Avian Flu Spread

- Human Death Toll from Bird Flu Tops 100

- Bird Flu Jumps to Cat in Germany

- New Bird Flu Concerns Italy, France, Egypt, India

- Tests Find Bird Flu in Egypt, France

- Bird Flu Reaches Western Europe

- Avian Flu Reaches Africa

U.S. Worries

- Bird Migration Has U.S. Experts Watching For Flu

- U.S. Not Prepared for Flu Pandemic

- Deadly Flu Will Reach U.S., Says Bird Migration Expert

- Bird Flu Pandemic Imminent, Health Official Says

- Avian Flu Could Reach U.S. Next Year

Flu Science

- SPECIAL REPORT: FLU FEARS

- Possible Path to Humans for Avian Flu Found

- Insides of Flu Virus Revealed

- Amid Avian Flu Fears, Other Bugs Far More Deadly

- Trojan Ducks: One More Possible Flu Carrier

- Scientists Recreate 1918 Flu Virus From Scratch

SPECIAL REPORT: FLU FEARS

What it is and how it affects us.

How to prevent and treat the flu.

How flu could become a global killer.