How Do Trivia Masters Do It? The Right Answer Is ‘Brain Efficiency.’

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

We all have that friend who "knows everything," wins at trivia and can have a conversation on just about any topic and seem knowledgeable. Turns out, these smarty-pants have very efficiently paved brains, a new study suggests.

A group of neuroscientists at the Ruhr-University Bochum and Humboldt University of Berlin, both in Germany, analyzed the brains of 324 people with varying degrees of general knowledge (like the kind of information that would come up in a game of trivia). Researchers gave these participants over 300 questions touching on various fields, such as art, architecture and science, to gauge the individuals' level of general knowledge, also known as semantic memory.

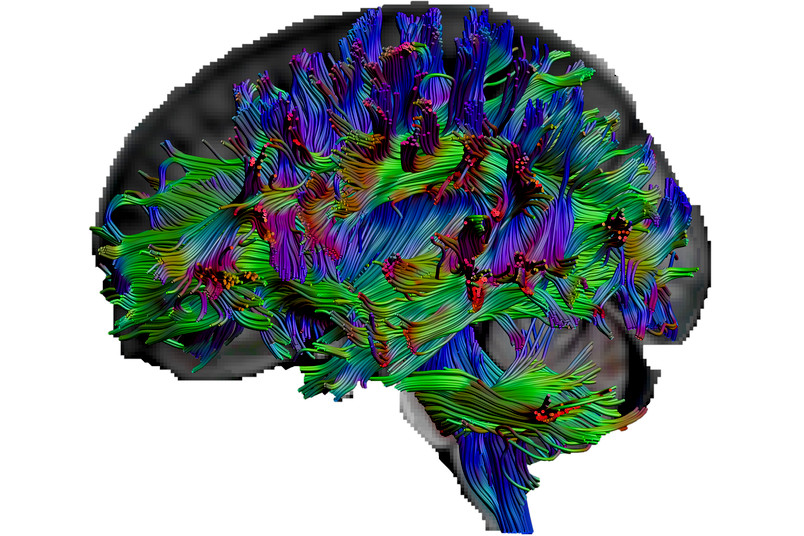

Investigators used a kind of magnetic resonance imaging known as diffusion tensor imaging to track the water that flows around the brain — which typically follows along the paths paved between brain cells. So, by tracking the water during brain scans, the researchers were able to "see" the connections. [Inside the Brain: A Photo Journey Through Time]

Results showed that those subjects who had retained, and could recall, more general knowledge had much more-efficient brain connections — stronger and shorter connections between brain cells. But the researchers didn't find any association between more general knowledge and more brain cells.

It makes sense that people who have more general knowledge have more-efficient brain connections, said study lead author Erhan Genc, a researcher in the Department of Biopsychology at the Ruhr-University Bochum.

Different bits of general knowledge get stored in various spots across the brain, he said. Imagine a simple question: What year did the moon landing happen? We might have "moon" stored in one area, "moon landing" in another and even the year the event happened in another. So, in order to answer the question, the brain has to connect "moon" to "moon landing" to "year," and it does so through these connections. It stands to reason that if the connections are more efficient, that information can travel quickly and easily, he said. [What If Humans Were Twice As Intelligent?]

But it's not clear why some people have more-efficient brain connections than others, he added. Perhaps some people are born with a more efficient brain architecture, or perhaps someone who acquires more general knowledge also generates more-efficient connections, because they use this knowledge all the time.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"With our study, we cannot solve this issue," Genc told Live Science. In order to do that, the researchers would need to track individual people across time to see how their brains change — something the scientists hope to look at in the future.

Being able to retain general knowledge doesn't necessarily mean that you're "smarter," Genc added. That's another kind of intelligence, called "fluid intelligence," which is more about being able to problem-solve in new situations, he said. However, there is a slight correlation between smartness and greater general knowledge, he said.

The findings were published July 28 in the European Journal of Personality.

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus