Mysterious Radiation Cloud Over Europe Traced to Secret Russian Nuclear Accident

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

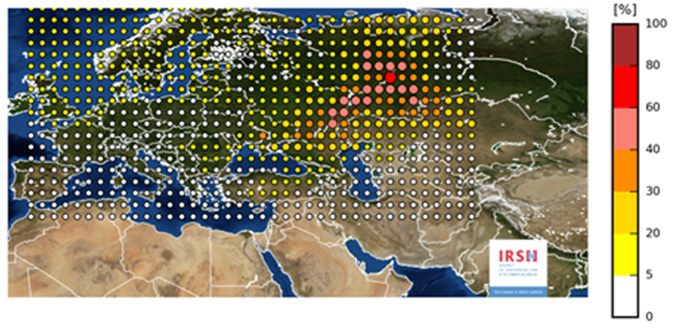

A vast cloud of nuclear radiation that spreadover continental Europe in 2017 has been traced to an unacknowledged nuclear accident in southern Russia, according to an international team of scientists.

The experts say the cloud of radiation detected over Europe in late September 2017 could only have been caused by a nuclear fuel-reprocessing accident at the Mayak Production Association, a nuclear facility in the Chelyabinsk region of the Ural Mountains in Russia, sometime between noon on Sept. 26 and noon on Sept. 27.

Russia confirmed that a cloud of nuclear radiation was detected over the Urals at the time, but the country never acknowledged any responsibility for a radiation leak, nor has it ever admitted that a nuclear accident took place at Mayak in 2017. [Top 10 Greatest Explosions Ever]

The lead author of the new research, nuclear chemist Georg Steinhauser of Leibniz University in Hanover, Germany, said that more than 1,300 atmospheric measurements from around the world showed that between 250 and 400 terabecquerels of radioactive ruthenium-106 had been released during that time.

Ruthenium-106 is a radioactive isotope of ruthenium, meaning that it has a different number of neutrons in its nucleus than the naturally occurring element has. The isotope can be produced as a byproduct during nuclear fission of uranium-235 atoms.

Although the resulting cloud of nuclear radiation was diluted enough that it caused no harm to people beneath it, the total radioactivity was between 30 and 100 times the level of radiation released after the Fukushima accident in Japan in 2011, Steinhauser told Live Science.

The research was published today (July 29) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ruthenium release

The cloud of radiation in September 2017 was detected in central and eastern Europe, Asia, the Arabian Peninsula and even the Caribbean.

Only radioactive ruthenium-106 — a byproduct of nuclear fission, with a half-life of 374 days — was detected in the cloud — Steinhauser said.

During the reprocessing of nuclear fuel — when radioactive plutonium and uranium are separated from spent nuclear fuel from nuclear power reactors — ruthenium-106 is typically separated out and placed into long-term storage with other radioactive waste byproducts, he said.

That meant that any massive release of ruthenium could only come from an accident during nuclear fuel reprocessing; and the Mayak facility was one of only a few places in the world that carries out that sort of reprocessing, he said.

Advanced meteorological studies made as part of this new research showed that the radiation cloud could only have come from the Mayak facility in Russia. "They have done a very thorough analysis and they have pinned down Mayak — there is no doubt about it," he said.

The accident came a little more than 60 years since a nuclear accident at Mayak in 1957 caused one of the largest releases of radiation in the region's history, second only to the 1986 explosion and fire at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant, which is now in the Ukraine. [Chernobyl Nuclear Disaster 25 Years Later (Infographic)]

In the 1957 accident, known as the Kyshtym disaster after a nearby town, a tank of liquid nuclear waste at the Mayak facility exploded, spreading radioactive particles over the site and causing a radioactive plume of smoke that stretched for hundreds of miles.

Nuclear accident

The study showed that the 2017 accident at Mayak was unlikely to have been caused by a relatively simple release of radioactive gas, Steinhauser said. Rather, a fire, or even an explosion, might have exposed workers at the plant to harmful levels of radiation, he added.

Russia has not acknowledged that any accident occurred at the Mayak facility, maybe because plutonium is made there for thermonuclear weapons. However, Russia had established a commission to investigate the radioactive cloud, Steinhauser said.

The Russian commission ruled that there was not enough evidence to determine if a nuclear accident was responsible for the cloud. But Steinhauser and his team hope it may look again at this decision in the light of the new research.

"They came to the conclusion that they need more data," he said. "And so we feel like, okay, now you can have all of our data — but we would like to see yours as well."

Any information from Russia about an accident at the Mayak facility would help scientists refine their research, instead of having to rely only on measurements of radioactivity from around the world, Steinhauser said.

The international team of scientists involved are keenly interested in learning more about its causes. "When everybody else is concerned, we are almost cheering for joy, because we have something to measure," he said. "But it is our responsibility to learn from this accident. This is not about blaming Russia, but it is about learning our lessons," he said.

- Images: Chernobyl, Frozen in Time

- 15 Secretive Places You Can Now See on Google Earth (And 3 You Can't)

- Lessons From 10 of the Worst Engineering Disasters in US History

Originally published on Live Science.

Tom Metcalfe is a freelance journalist and regular Live Science contributor who is based in London in the United Kingdom. Tom writes mainly about science, space, archaeology, the Earth and the oceans. He has also written for the BBC, NBC News, National Geographic, Scientific American, Air & Space, and many others.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus