50-Million-Year-Old Fossil Shows School of Baby Fish in Their Final Moments

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

One fish, two fish, dead fish, cool fish.

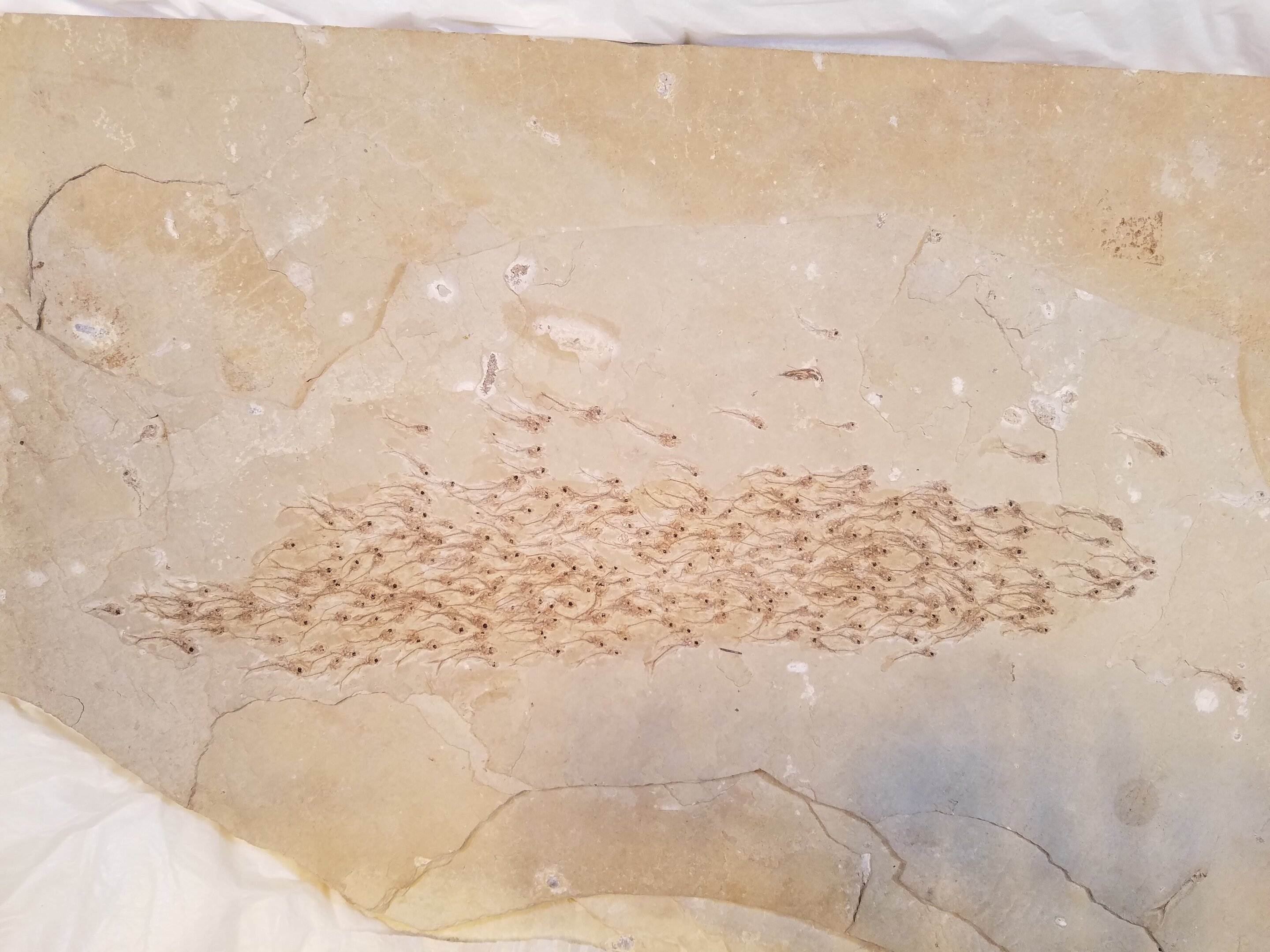

There's room for all types in a newly described fossil that shows 259 baby fish swimming together in a school, approximately 50 million years ago. According to the authors of a new study published Wednesday (May 29) in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, this ex-school may be the earliest known fossil evidence that prehistoric fish swam in unison, just as modern fish do today.

A team of Arizona researchers stumbled upon this remarkable rock during a visit to the Oishi Fossils Gallery of Mizuta Memorial Museum in Japan. Working with the museum, the researchers determined that the fishy fossil probably originated in America's Green River Formation, a geologic stratum in present-day Colorado, Wyoming and Utah that contains a trove of fossils dating to between 53 million and 48 million years ago.

The fish in question all belonged to the extinct species Erismatopterus levatus, and were apparently entombed together in the midst of a routine swim that may have been cut short by an underwater avalanche of sand, the researchers wrote. All but two of the wee specimens were swimming in the same direction and in a close-knit formation.

To prove that the fish were indeed swimming in a school and not just fossilized that way by coincidence, the researchers ran a series of simulations to reproduce the group's likely movements. The simulations showed that the fish were apparently not only swimming in unison, but also did so according to a timeless set of behavioral rules that still show up today.

"We found traces of two rules for social interaction similar to those used by extant fishes: repulsion from close individuals and attraction towards neighbors at a distance," the researchers wrote in their study. In other words, individual fish swam close together, but not so close that they crashed.

According to the authors, this ancient slab of dead swimmers shows that fish (and possibly other animals) evolved coordinated group behaviors at least 50 million years ago. This synchronized swimming seems to have successfully saved the fish from being devoured by a predator, even if it could not save them from becoming a museum exhibit.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

- Gallery of Fantastic Fossils

- Image Gallery: Fossils Reveal Rhino's Grisly Death

- Photos: The First Dino Fossil Found in Washington

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus