Robot Fish Leads the School

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

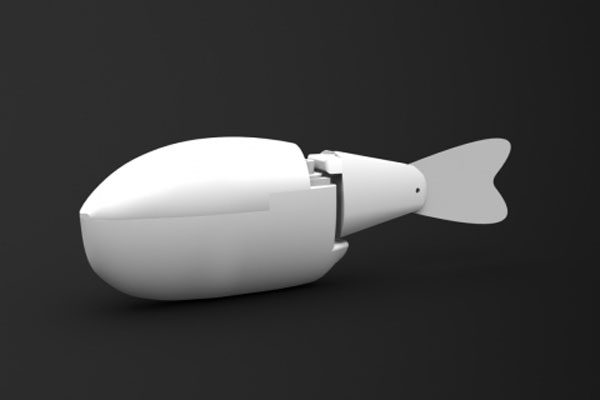

Engineers have designed a robot fish that, under the right conditions, becomes head of the pack.

Robots like this one could be used to lead schools of fish away from oil spills, underwater turbines or other dangers, and they could also offer scientists a new tool with which to study fish behavior, said Maurizio Porfiri, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at Polytechnic Institute of New York University.

Nature offers plenty of inspiration for engineers building robots, and others have used this approach, called biomimicry, to study animal behavior, confronting live dogs with a robot dog and live cockroaches with mechanical cockroaches. The fish study is one of few to attempt to integrate robots into collective animal behavior, in this case, the schooling of fish, according to Porfiri.

The robot in question was designed to swim, but not look, like a fish. Made of plastic and about 4 inches (10 centimeters) long, it has a rigid body and a two-segmented tail. The end of the tail is flexible and propelled from side to side by a motor.

Porfiri and fellow researcher Stefano Marras placed the robot fish in a water tunnel with smaller, live fish, called golden shiners. The researchers varied the speed at which the robot beat its tail and the speed of the flowing water. They then watched to see where the live fish positioned themselves.

When the robot didn't move, the fish did not respond to it. But, with the right combination of tail beats and water velocity, about 60 percent to 70 percent of the live fish fell in behind the robot, Porfiri said.

They found that if the water was flowing at about 5.5 inches (14 centimeters) per second, the fish responded best to a tail-beat frequency of about two cycles per second. If the velocity of the water increased, then the fish responded better to three beats per second.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Fish like to be in the wake," Porfiri said. "We measured the tail-beat frequency of the fish in front of the robot and in this particular location (in back), and if you find a fish that is holding station in back of the robot, it swims at the same speed, but beats at a lower frequency."

Swimming in the robot's wake allows the fish to save energy, in other words.

The research, funded by the National Science Foundation, was published online Feb. 22 in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Wynne Parry on Twitter @Wynne_Parry. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus