'That Can't Be Real!' Deep-Sea Explorers Find Trippy, Rainbow-Colored Wonderland

Deep in the Gulf of California, scientists have discovered a fantastical expanse of hydrothermal vents, full of crystallized gases, glimmering pools of piping-hot fluids and rainbow-hued life-forms.

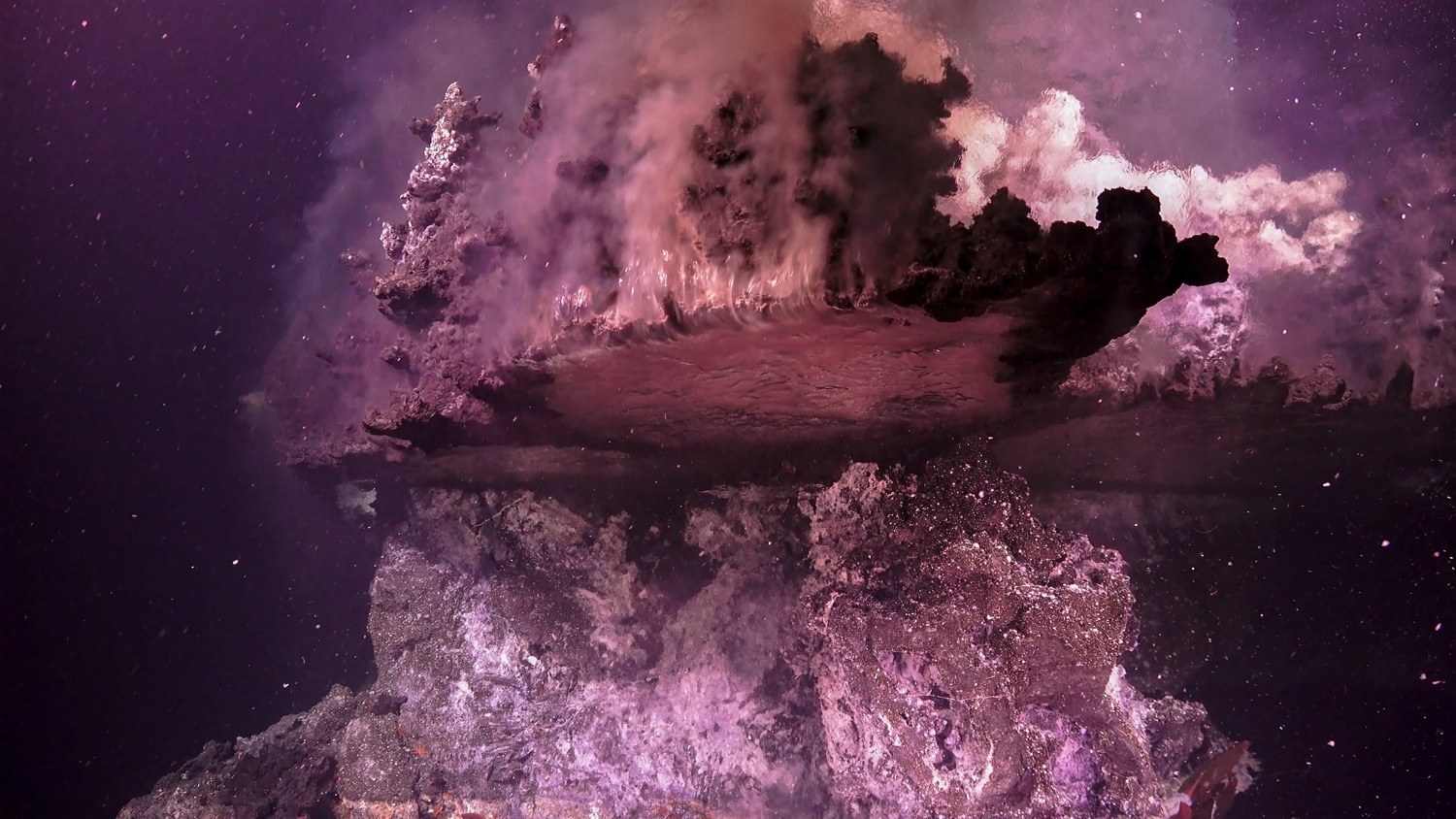

Punctuating it all are towering structures made of minerals from the vents, looming as tall as 75 feet (23 meters). A decade ago, scientists visiting this spot saw nothing unusual; this psychedelic seascape seems to have built up around an increase in hydrothermal venting — spots in the seafloor where mineral-laden and superhot water jets out — in the last 10 years.

"Astonishing is not strong enough of a word," said Mandy Joye, a marine biologist at the University of Georgia, who led the team that discovered the vents. [See Stunning Photos of the Newfound Hydrothermal Vent System]

Shocking discovery

"We saw a lot of really interesting topography, which made me scratch my head," Joye said. Chemical traces in the water also suggested there might be hydrothermal vents nearby.

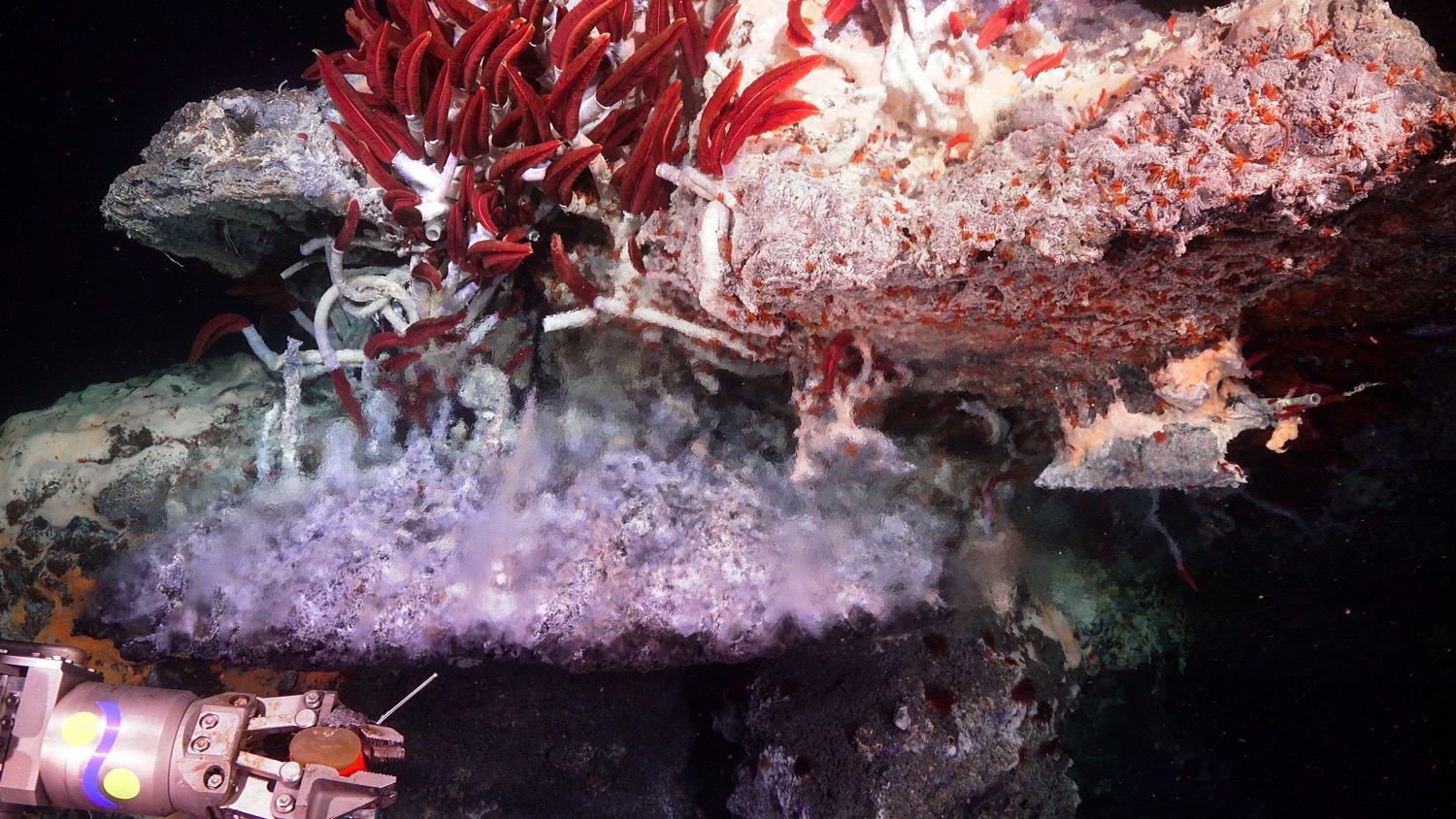

In February, the team launched another expedition, sending autonomous vehicles equipped with high-definition cameras into the deep from the decks of the Schmidt Ocean Institute's research vessel, Falkor. Nearly 6,000 feet (1,800 m) below the surface, they saw the vents that were carpeted with microbes, marine worms and species they didn't recognize.

"It was a shock, to put it mildly," Joye told Live Science. "I think my jaw literally hit the floor."

Unreal environment

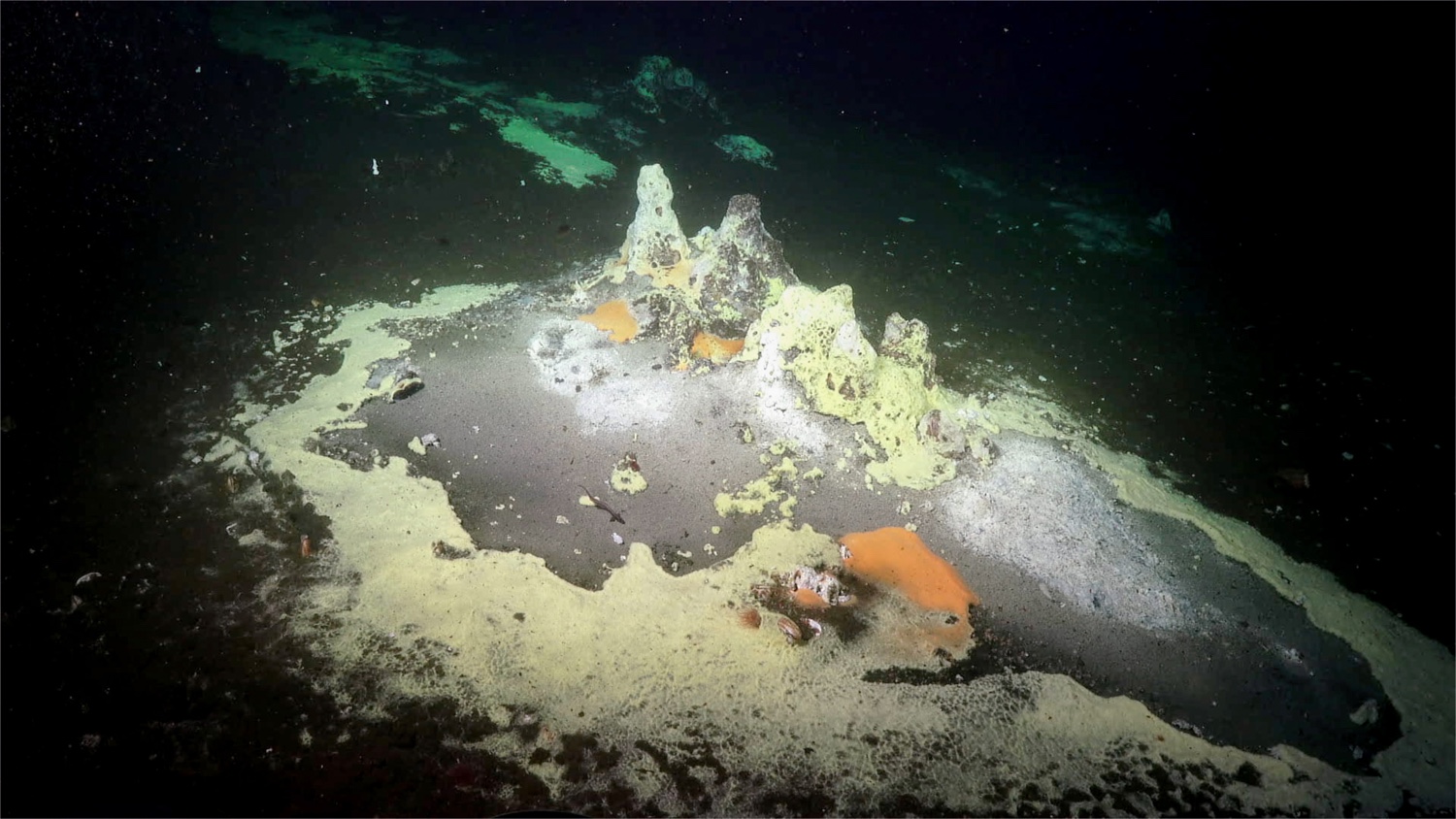

The team had discovered a hydrothermal vent site that hadn't existed in 2008. Most likely, Joye said, new vents have opened since then, or the rate of hydrothermal fluid flow has increased. The dissolved minerals and metals in the fluid react with seawater to create huge "pagodas," some as thick as 49 feet (15 m) in diameter and many rising 33 feet (10 m) above the seafloor. [Gallery: Creatures of the Deepest Deep-Sea Vents]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In some places, the fluid flow created ledges, or flanges, that trap pools of the sulfide- and methane-rich fluid underneath. The pools refract light, creating a silvery, mirror-like effect, Joye said. In some pools, the team saw delicate mineral precipitates a few inches long that looked like feathers. No one knows what they are, Joye said.

"It was just a constant barrage of, 'You have got to be kidding me — that can't be real,'" she said.

Among the other surprises at the site were bizarre methane hydrates — natural gas bubbles trapped in a crystalline framework of ice. The methane hydrates at these vents, though, looked strangely irregular, with almost a melted appearance, Joye said.

The researchers don't yet know why the features looked like that. It could be the high pressure and extreme temperatures at the site, Joye said. The ocean water is just 35.6 degrees Fahrenheit (2 degrees Celsius), while the hydrothermal fluids are a toasty 690.8 F (366 C). Or there may be impurities in the methane gas that cause the strange shapes.

Mystery life

Among the other mysteries at the vent site is the proliferation of life carpeting the hot towers of mineral-rich water spewing from the vents. Some were recognizable, like the Riftia tube worms that harbor sulfur-eating symbiotic bacteria. Others were totally new to science. The towers are home to rainbow-colored mats of microbes, Joye said, ranging from pink to orange to white to yellow to purple.

"I've never seen a purple microbial mat, ever, anywhere," Joye said. The researchers are now using genetic sequencing to study the microbes and to learn whether temperature, water chemistry or some other factor determines their color.

The researchers are also delving deeper into the composition of the hydrothermal fluid, which they've already found to be rich in manganese and iron. Finally, Joye said, the team's virologist is studying the viruses that infect the microbes at the site.

"These kinds of things don't happen very often," Joye said. "I'm just counting the days until I can go back."

- Gallery: Unique Life at Antarctic Deep-Sea Vents

- Marine Marvels: Spectacular Photos of Sea Creatures

- Photos: Primordial Worm Snatched Prey with Spines on Its Head

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus