Cryptocurrency: Blockchains, mining and environmental impact

What is cryptocurrency and how does it work?

Cryptocurrency is money that is 100% virtual. This digital money, whose name comes from the Greek word "crypto," meaning "hidden" or "secret," is gaining steam as more companies accept it as payment, and more people invest in various crypto coins in the stock market.

Cryptocurrencies have roots at the fringes of society. They've infamously been sought as ransom payment or used to make illegal purchases because transactions aren't traceable by conventional means, although they do leave digital traces.

Now, cryptocurrencies are more mainstream than ever before. Sky-high values and astonishing price drops have attracted media attention and speculative investors. In February 2019, financial giant JPMorgan Chase issued its own cryptocurrency — a first among traditional financial institutions. About 220 million people used cryptocurrencies as of June 2021, according to Crypto.com.

Cryptocurrencies are "non-governmental digital assets that are widely tradeable," said James Angel, an associate professor at Georgetown University in Washington D.C., who studies financial technology. Since Bitcoin — perhaps the best known type of cryptocurrency — was first suggested in 2008, many variations have emerged. There are now thousands of cryptocurrencies.

Put it on the blockchain

Many cryptocurrencies use blockchain technology. The idea behind blockchain is to keep a "distributed ledger," sort of like a database of information that multiple parties have independent access to and must agree upon to make any changes. These ledgers store information in groups, or blocks. Once a block has reaches capacity, it is closed and linked to the preceding block, forming a chain of information called a blockchain.

Each transaction made with cryptocurrency is added to this ledger, and there are many copies of the ledger that are digitally accessible to users on the crypto's network. No one user is able to alter information on a blockchain ledger without permission from everyone else involved in a transaction, and a clear record is kept of their actions. This means that a blockchain could prevent hacking attempts that rewrite ledgers or transfer funds without a log of changes.

Related: How blockchain can benefit space exploration

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Blockchain has been hyped as a security revolution, but in some ways it simply shifts the vulnerabilities of sensitive information. For example, a customer might not trust that their bank can keep their account balance protected, but if the customer loses their ATM card or online passwords, the bank will allow the customer to regain access to their money. On the other hand, a cryptocurrency that incorporates a blockchain puts more responsibility of security on the customer, so that a stolen or lost password could mean losing access to their funds forever.

Still, blockchain offers the possibility of doing familiar transactions more efficiently. "The underlying technology is very useful," Angel said.

Types of cryptocurrencies

Not all cryptocurrencies are intended to be used in the same way as traditional currencies. There are three main categories of cryptocurrency, according to Angel:

Utility tokens can be redeemed for services (or "utilities"), for example, on a network run by Ethereum, an open-source computing platform and operating system that has its own cryptocurrency. These services could be anything from online games and gambling, to marriage licenses.

Right now, one key offering from utility tokens is facilitating something called a smart contract. These are agreements in computer code that use a blockchain to automate the normal time-consuming communication between multiple parties. The utility tokens work like arcade tokens that can be used for a variety of games, so long as they're in the same arcade. That is, a variety of services may be provided by the same company that issues the utility token.

Smart contracts can also be used independently of cryptocurrencies. For example, in the state of Ohio, legislation was introduced to allow the use of smart contracts to register a car title. A smart contract could automatically coordinate agreements between a buyer, a car dealership, a bank and an insurance company.

These types of contracts could streamline everyday transactions, but we might not even notice when they've been introduced. "It's probably going to be invisible to you in a lot of ways," Angel said, because a smart contract could replace much of the administrative work that goes on behind the scenes, while keeping roughly the same terms in place.

There are also payment tokens, like Bitcoin, which most closely resemble familiar forms of money, and can be exchanged for goods with anyone who will accept them as payment. Bitcoin is now accepted at some major online stores, such as the tech retailer Newegg, but it's far from being universally accepted. "I don't think any of us are going to walk into a fast food restaurant any time soon and buy a burger with Bitcoin," Angel said.

And then there are security tokens. Rather than conferring some tangible utility, these tokens are used to certify ownership of something, similar to owning stock in a company. The classification of any cryptocurrency, which may be disputed, makes a difference in how it will be regulated. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission has declared its intent to treat most cryptocurrencies similarly to public stock, particularly in instances where the coin isn't exchanged for goods or services, but serves as a financial interest in an enterprise.

What is cryptocurrency mining?

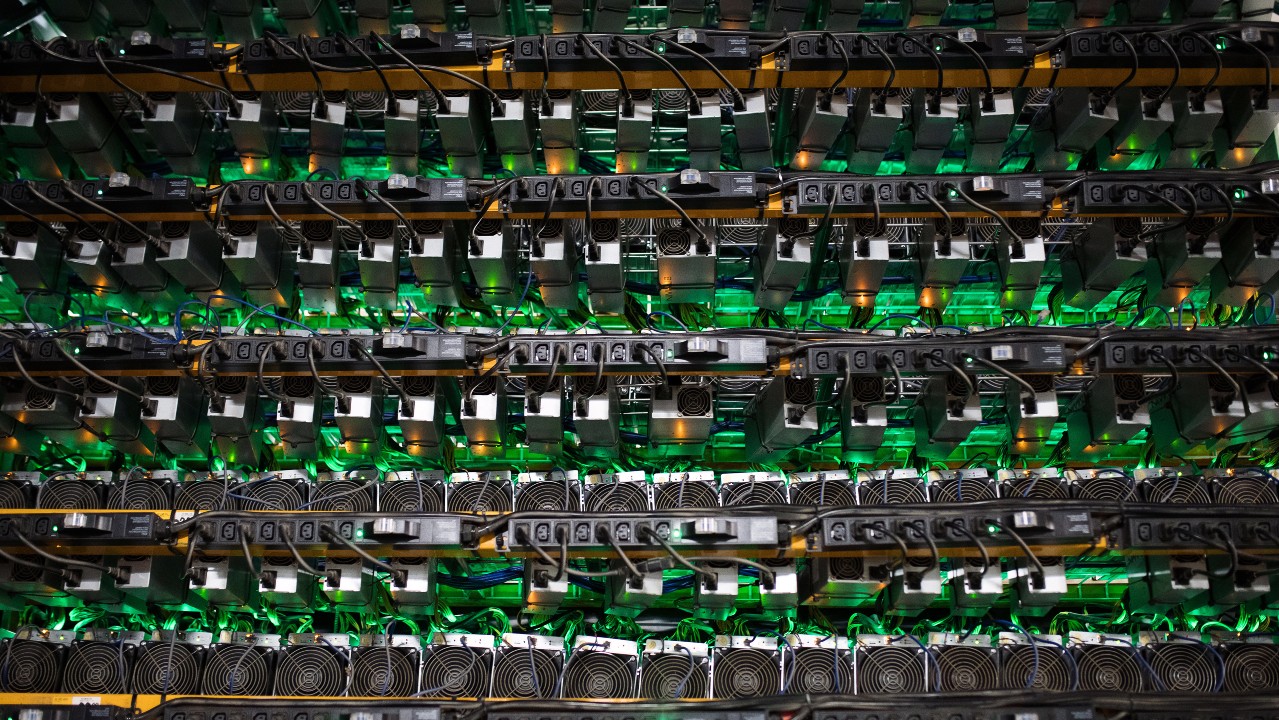

An enormous amount of electricity use is built into the design of cryptocurrency, especially Bitcoin. Combined with its popularity, this has led to scrutiny of Bitcoin's energy consumption.

Rather than have a centralized set of computers that process transactions, users handle the daily operations of the Bitcoin economy. That involves user-owned computers running software that helps perform blockchain transactions. To incentivize users, the software also attempts to solve a mathematical puzzle through brute force — by guessing and checking one solution after another. When a solution is found, the lucky user is rewarded with Bitcoin. These users are called miners, and the process of running energy-consuming computers to earn coins is called mining. Although not all bitcoin users need to mine for Bitcoin, mining is essential to Bitcoin transactions.

It's been estimated that Bitcoin miners globally use electricity on the scale of entire countries like Ireland or Austria. "The environmental impact of Bitcoin in its current form is just totally unacceptable," Angel said.

Not only is the environmental impact concerning, but cryptocurrencies are also "very volatile, [and] there are a lot of scams out there," Angel said. "No one knows what they're really worth."

Is cryptocurrency bad for the environment?

The process of trading and mining cryptocurrencies requires enormous amounts of energy.

The annual energy requirements for Bitcoin mining are extensive. On March 1 2022, the estimated electrical computations of the Bitcoin network was 204.50 terawatt hours, according to the Bitcoin Energy Consumption Index (BECI) which was created by the Digiconomiust. This is the same amount of energy consumed by Thailand each year.

According to the Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index (CBECI), developed recently by the University of Cambridge, the Bitcoin network accounts for 0.59% of global electricity consumption and 0.29% of its energy consumption.

Energy consumption on this scale wouldn’t be an issue of the environment if the world’s power production was carbon neutral and from renewable sources – however, that’s simply not the case. In 2019, around 64% of all the electricity generated across the globe was produced from exploiting fossil fuels, according to Our World in Data, a project of the non-profit organization Global Change Data Lab. Therefore, the high energy demands of the bitcoin network can heavily impact the environment.

According to the BECI, the annual carbon footprint of the Bitcoin network is 114.06 Megatonnes as of March 1 2022, which is comparable to the footprint produced by the entire Czech Republic. Only 39% of the energy used to fuel Bitcoin came from renewable energy – predominantly hydroelectric power – according to Cambridge University’s 2021 Global Cryptoasset Benchmarking Study.

Cryptocurrencies have also enabled fossil fuels stations that would otherwise have closed down to remain open. For example – Greenidge Generation was once a coal power plant in New York City but has now transformed into a natural gas plant and one of the biggest Bitcoin miners in the U.S, according to the Columbia Climate School. Between 2019 and 2020, the power plants' greenhouse emissions increased ten-fold, with carbon dioxide equivalent emissions reaching 243,103 tons in December 2020, according to a letter sent to the NYS Department of Environmental Conservation by non-profit organization EarthJustice. Greenidge claims it is now carbon-neutral through purchasing carbon offsets and proposes that it will invest in future renewable energy projects. Cryptocurrency has the potential to support more fossil fuel industries in the same way as Greenidge, which might otherwise go out of business, thus further contributing to global emissions.

At present, the high energy consumption of cryptocurrencies means that it negatively impacts the environment, but it doesn't have to. Simply shifting the supply of energy from finite resources and investing in renewable energy sources would almost completely reduce its environmental impact.

Additional resources

- Read an explanation of blockchain technology from IBM.

- Enroll in the free online Coursera course "Bitcoin and Cryptocurrency Technologies," offered by Princeton University.

- Learn more about how cryptocurrency is regulated around the world from the Library of Congress.

Bibliography

- Live Science. "Did You Buy Bitcoins? Your Brain's Anatomy Might Be to Blame." April 9, 2018.

- The New York Times. "JPMorgan Chase Moves to Be First Big U.S. Bank With Its Own Cryptocurrency." Feb. 14, 2019.

- Satoshi Nakamoto. "Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System."

- Wired. "There's No Good Reason to Trust Blockchain Technology." Feb. 6, 2019.

- Space.com. "How Blockchain Can Benefit Space Exploration (Op-Ed)" June 27, 2018.

- Investopedia. "What Is a Blockchain?" Feb. 16. 2022.

- Bankrate. "What is Bitcoin mining and how does it work?" Jan. 7, 2022.

- Cryptos.com. "Utah County, UT Records Marriage Licenses on the Ethereum Blockchain."

- Scott DutfieldContributor

- Laura GeggelManaging Editor

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus