Mendeleev's Periodic Table Draft Is Virtually Unrecognizable — But It Changed Science Forever

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

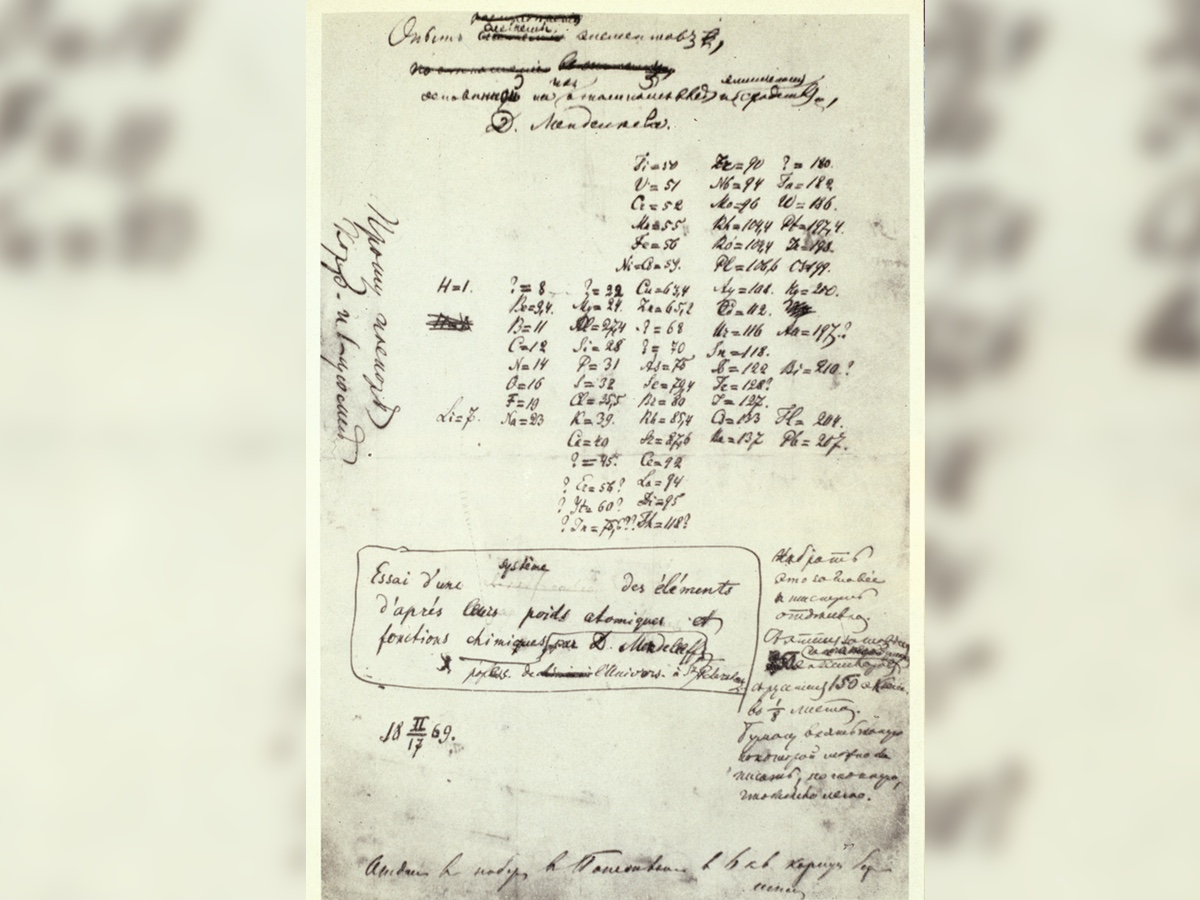

On Feb. 17, 1869, Russian chemist Dmitri Mendeleev published his first attempt to sort the building blocks of life into orderly groups. Now, 150 years later, we know the fruits of his labor as the Periodic Table of Elements — a quintessential piece of classroom wall art and indispensable research tool to anyone who's ever picked up a beaker.

As you can see for yourself in the hand-scrawled draft above, Mendeleev's first table looked very different than the one we know today. In 1869, only 63 elements were known (compared with the 118 elements we have identified today). As a student at Heidelberg University in Germany and later as a professor at St. Petersburg University, Mendeleev realized that by grouping elements according to their atomic weights, certain types of elements periodically occurred. [Elementary, My Dear: 8 Little-Known Elements]

Mendeleev honed this "periodic system," as he called it, by writing down the names, masses and properties of each known element on a set of cards. According to science historian Mike Sutton of Chemistry World, Mendeleev then laid these cards down before him — solitaire-like — and started shuffling them around until he found an order that made sense.

Ultimately, Mendeleev's eureka moment came to him in a dream, Sutton wrote. When he awoke, he arranged his element cards in vertical columns in order of increasing atomic weight, starting a fresh column to group elements with similar properties into the same horizontal row. With these guiding principles, he eventually created the world's first Periodic Table.

Mendeleev was so confident in his system that he left gaps for undiscovered elements, and even predicted (correctly) the properties of three of those elements. Those three elements — known now as gallium, scandium and germanium — were discovered within the next three years and matched Mendeleev's predictions, helping to solidify the reputation of his table, Sutton reported.

The table wasn't perfect (Mendeleev was unable to locate hydrogen using his system, for example), but it laid a solid groundwork for generations of chemists to build upon over the next 150 years.

- Rare Artifacts from the History of Science Auction (Photos)

- 10 Odd Tales About Famous Scientists

- Beyond Tesla: History's Most Overlooked Scientists

Originally published on Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus