Why This 'Atmospheric River' Could Cause Mudslides and 'Roofalanches' in California

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

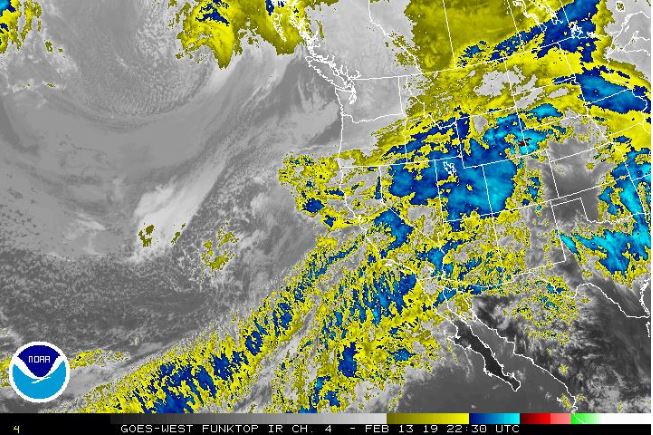

Californians are experiencing some unusually nasty winter weather this week as an "atmospheric river" passes through most of the state, bringing howling winds and heavy rain.

The storm arrived on Tuesday night (Feb. 12) in Northern California and continued into Wednesday (Feb. 13), leading the National Weather Service (NWS) to issue warnings of flash flooding, mudslides and high winds in the region. It is forecast to bring "excessive rainfall" to Southern California on Thursday (Feb. 14), according to the NWS.[Weirdo Weather: 7 Rare Weather Events]

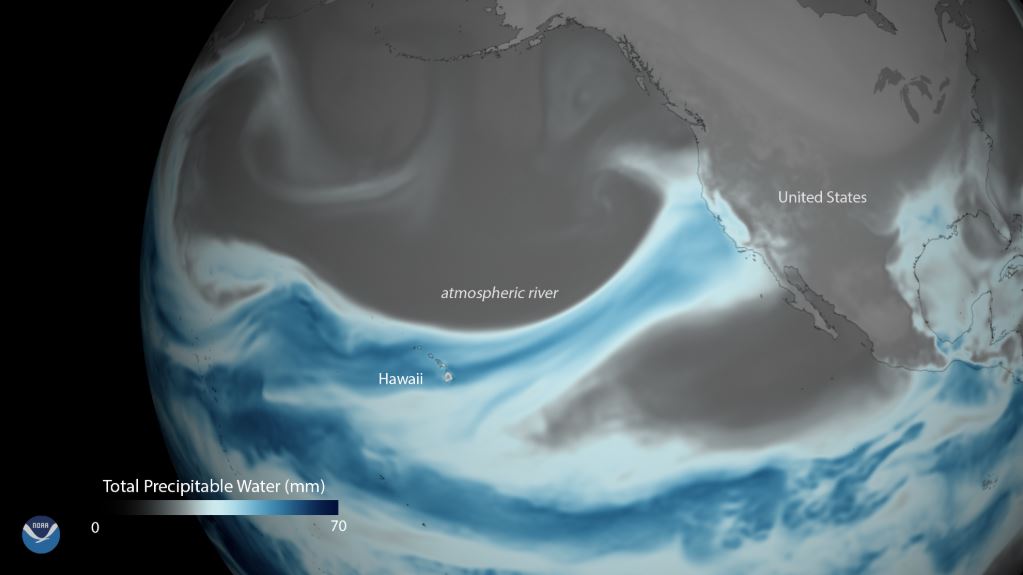

Atmospheric rivers are huge "rivers in the sky" that cause moisture from the tropics to flow north, from California to Canada. These huge weather systems can carry many times the freshwater that flows through the mighty Mississippi River, local news outlet KQED reported.

"They're the biggest freshwater rivers on Earth," F. Martin Ralph, the director of the Center for Western Weather and Water Extremes in La Jolla, California, told KQED.

These atmospheric rivers of condensed water vapor can easily be 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometers) long and 300 miles (482 km) wide, Ralph said. When an atmospheric river brings moisture from Hawaii to the Western U.S. — as is the case with the current storm — it's known as the Pineapple Express.

Atmospheric rivers can bring much-needed rain — or wreak havoc by dumping heavy rain or snow when they make landfall, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). California has recently experienced storms, meaning the current downpour is falling on waterlogged soil. Summer wildfires also scorched the earth in several areas of California, and burn scars can be more prone to flash flooding and debris as well, according to the NWS.

On Wednesday morning, 24-hour rainfall totals were as high as 3 inches (7.6 centimeters) in some parts of the Northern Bay Area, with San Francisco receiving about 1.5 inches (3.8 cm) of rain, according to the NWS. Residents along the Bay Area coast and hills may face high winds from 25 to 35 mph (40 to 56 km/h) with gusts up to 60 mph (97 km/h), according to the NWS. Social media was abuzz with reports of downed trees and flash flooding. In the Sierras, the NWS warned that the atmospheric river could cause "roofalanches," or the sudden release of snow from already snow-packed roofs, which can pose a serious hazard.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Earlier this month, Ralph and his colleagues developed a new scale to describe the strength of atmospheric rivers. The scale, which was described in the February issue of the journal Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, ranks these weather events using categories "1 to 5," with Category 1 indicating a "weak" storm and Category 5 indicating an "exceptional" one. The ranking is based on the amount of water vapor the storm carries, and how long it dumps moisture on a given area, according to a statement. The scale also indicates the extent to which the storm is likely to be beneficial — by bringing much-needed rain to replenish reservoirs after a drought, for example — or hazardous, leading to flooding and mudslides. The current storm is a "Category 3," according to local news outlet CBS San Francisco.

Tia Ghose contributed reporting.

- 9 Tips for Exercising in Winter Weather

- Fishy Rain to Fire Whirlwinds: The World's Weirdest Weather

- 10 Surprising Ways Weather Has Changed History

Originally published on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus