World's First Dolphin Spinal Tap Cranks Marine Medicine Up to 11

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

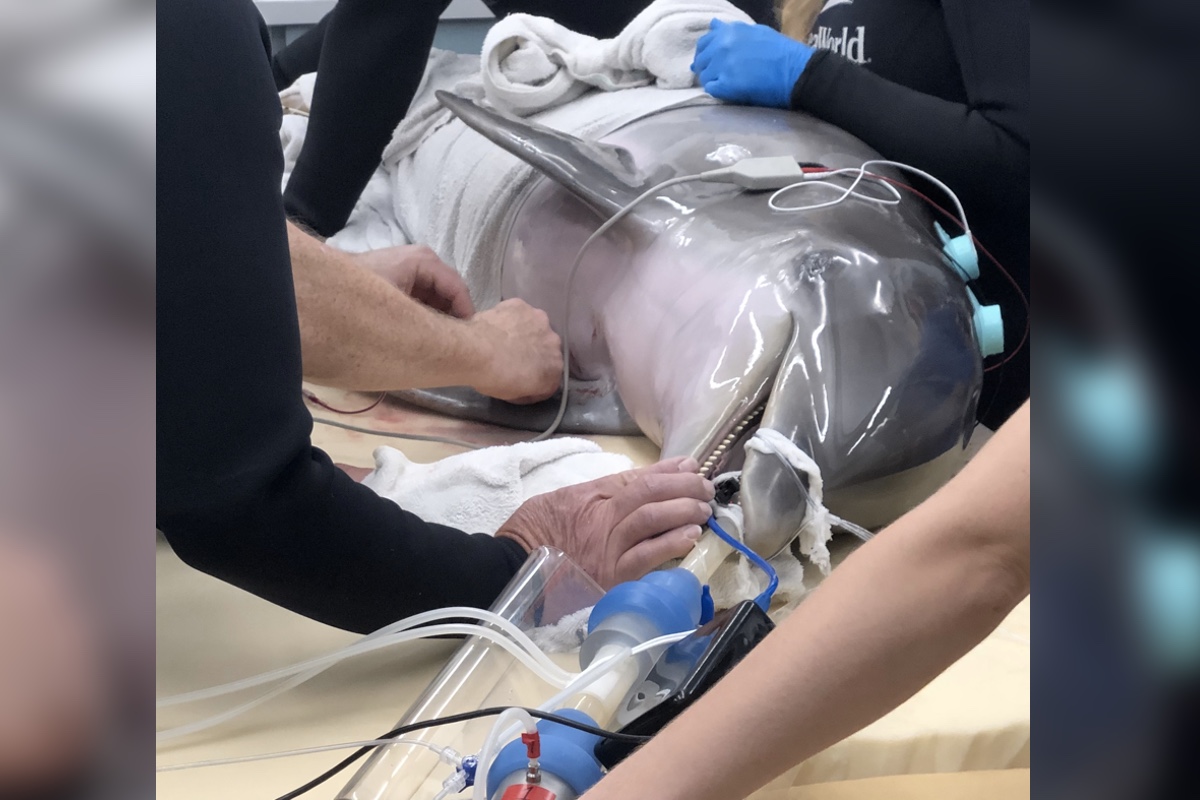

In an apparent world first, veterinarians have successfully performed a spinal tap on a live dolphin.

That dolphin, who underwent the procedure at SeaWorld San Antonio, is named Rimmy. She is a bottlenose dolphin, about 3 or 4 years old, who was rescued from Texas' Sea Rim State Park off the Gulf of Mexico, where she was found sick and stranded in 2017.

While trying to diagnose the cause of Rimmy's stranding, vets saw that the dolphin was riddled with ailments, including pneumonia and "nasal parasites," Dr. Hendrik Nollens, vice president of SeaWorld's veterinary services, told ABC News. [Deep Divers: A Gallery of Dolphins]

Rimmy spent the next 14 months being treated at a special rehab center for stranded marine mammals, where researchers from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) decided she was too fragile and dependent on humans to return to the wild.

Before Rimmy could find a new home in captivity among other dolphins, however, she had to be tested for an infectious animal bacteria called Brucella, which can result in a several symptoms, including reproductive loss. When one of several tests came back positive, Rimmy's caretakers decided they needed to be 100 percent certain before deciding the dolphin's fate. If she had Brucella, she might not be able to ever interact with other dolphins, Nollens said.

The vets decided that Rimmy needed a lumbar puncture, commonly known as a spinal tap. — The procedure is used to collect cerebrospinal fluid, in order to diagnose diseases of the central nervous system. To keep Rimmy perfectly still for her spinal tap, vets anesthetized her. When Rimmy was unconscious, vets inserted a long, thin needle into the dolphin and collected a sample of spinal fluid for testing.

Good news: The results showed that Rimmy was "free and clear" of any bacteria, and that nothing was stopping her from living out the next chapter of her life among fellow dolphins.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

- In Photos: A Rare Albino Risso's Dolphin

- In Photos: The World's Most Endangered Marine Mammal

- The 10 Weirdest Sea Monsters

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus