Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The vaquita, an elusive porpoise that lives off the coast of Mexico, is the world's most endangered cetacean. New studies suggest that fewer than 100 of these creatures exist in the wild, and if enforcement measures aren't stepped up, the marine mammals could be extinct in four years. [Read the full story on the rare vaquita porpoises]

Cute faces

Vaquitas are the smallest porpoises, and measure just 4 to 5 feet (1.2 to 1.5 meters) in length. The rare creatures live in the Gulf of California, off the coast of Mexico. The species diverged from their porpoise cousins between 2 million and 3 million years ago, and are most closely related to Burmeister's porpoises, which live off the coast of South America. They have winsome, almost smiling faces, with eyes and mouths fringed with black, as if they are wearing mascara and lipstick. (Photo credit: Alejandro Robles)

Rarely spotted

The diminutive porpoises are incredibly shy and are rarely seen in the water. Most of the time, they are spotted when they turn up dead in a fisherman's net. (Photo credit: Tom Jefferson)

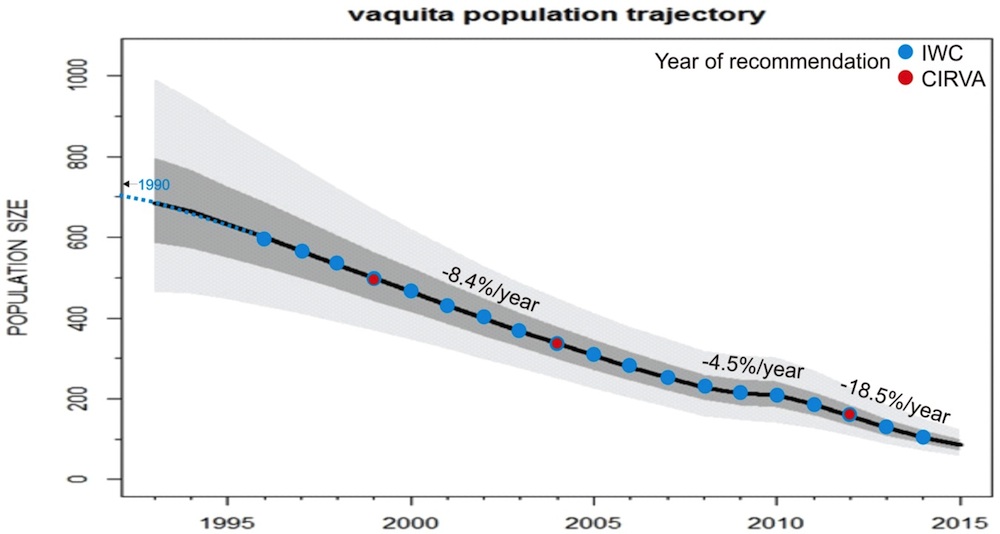

Decimated population

The population has been decimated in recent years, and the culprit is the unchecked use of gill nets to fish for totoaba, an endangered fish prized in China for its swim bladder. Gill nets are a kind of vertical netting that act like a wall in the water, and because the vaquitas can't see them, they get entangled and die. (Photo credit: Proyecto Vaquita)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Illegal and legal fishing

A July 2014 report found that just 100 of the vaquitas exist in the wild, and that the population had declined by 18.5 percent over the past year. If fishermen dont' stop using gillnets in the vaquita habitat and the decline continues unchecked, the creature could be extinct in the next four years. (Photo credit: CIRVA)

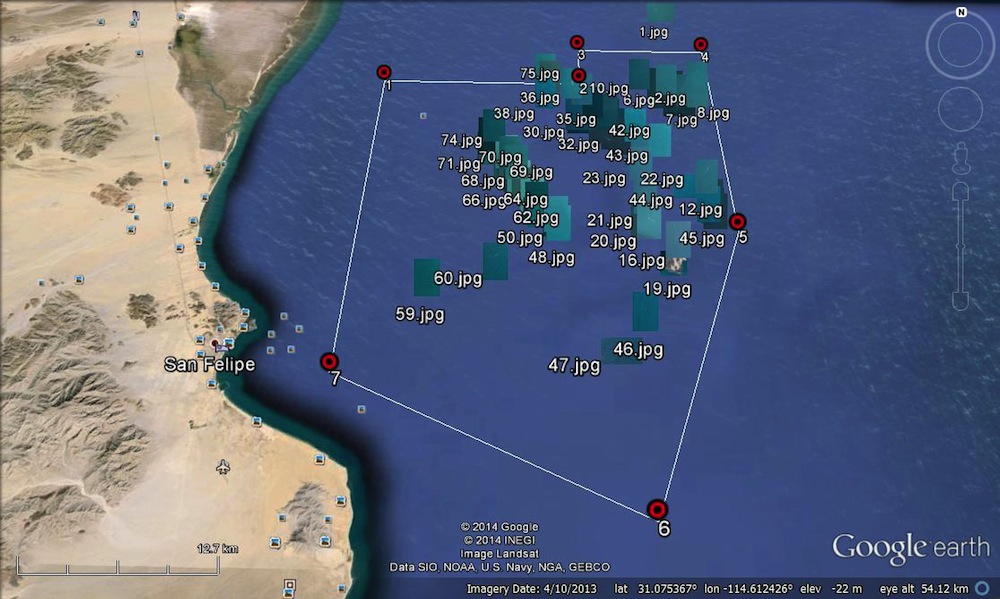

Flagrant violation

Currently, only about one-fifth of the vaquita's habitat is a protected area shielded from gillnet fishing. But pictures released in December revealed over 90 fishing vessels in that protected area, and 17 of those boats had gillnets. (Photo credit: Google Earth, via IUCN)

Stepped-up enforcement

The main hope for saving the vaquita is to make gill net fishing illegal in all of the vaquita's habitat, increase the number of boats patroling for illegal fishing, and make it ilelgal ot even have a gill net on baord when fishing in the protected waters, said Rebecca Lent, the executive director of the Marine Mammal Commission. (Photo credit: Omar Vidal/Proyecto Vaquita)

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus