Whale Album: Giants of the Deep

Sperm whale and diver

The male sperm whale (Physeter macrocephalus) is the largest living toothed predator on Earth. Its submarine-like shape is perfectly adapted for deep diving — it can swim down to at least 6,500 feet to feed. The whale’s massive bulbous head is about one-third of the animal’s length. It’s also a massive sound generator that helps the whale navigate.

Exhibition entrance

The entrance to Whales: Giants of the Deep at the American Museum of Natural History.

Whale teeth and baleen

Visitors will have the chance to examine the ways in which whales feed. Based on their evolutionary relationships, living whales can be divided into two types — baleen whales and toothed whales. Baleen whales are “batch feeders” — they use their plates of baleen to filter huge numbers of tiny prey out of the water. Toothed whales typically hunt their prey using echolocation. They either seize their prey individually with their teeth or suck them directly into their mouths and swallow them whole.

Blue whale heart

Blue whales are about 98 feet (30 meters) long — the largest animals to ever live. They can eat an astounding 4 tons (3,600 kilograms) of krill per day in the summer feeding season. The blue whale’s heart can weigh up to 640 kilograms (1,410 pounds) and is the size of a small car. A child could crawl through the blue whale’s largest blood vessel — and a life-size model in the exhibition allows children, and adults, to do just that.

Skeletons of whale ancestors

Whales are mammals, like humans, and their ancestors once lived on land. So how did they come to be so specialized for life in the sea? Within the exhibition, skeletons of fossil whales show visitors how the whale lineage evolved from land mammals to fully aquatic whales.

Andrewsarchus mongoliensis skull

This 3-foot-long skull belonged to Andrewsarchus mongoliensis, an extinct cousin of whales that lived on land some 45 million years ago. Like many ancient whale relatives, Andrewsarchus walked on four legs, and it likely had hooves. No other parts of its skeleton have been found to date, so scientists have studied the skull to learn about the evolutionary relationships and habits of this prehistoric animal. The cheek teeth are deeply worn, suggesting that the jaws were used to crush bone. Andrewsarchus clearly ate meat, though it’s not known whether it was a scavenger or an active predator.

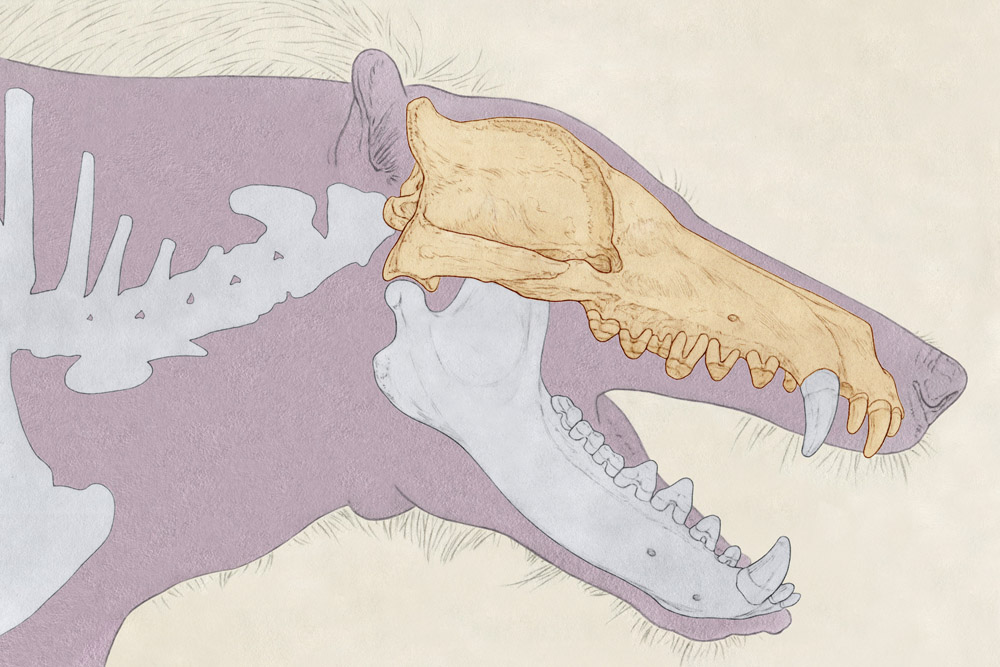

Andrewsarchus mongoliensis skull diagram

This illustration shows Andrewsarchus, a prehistoric cousin of whales. The spine, lower jaw, and fleshed-out form are reconstructed based on the existing skull (brown) and comparison to relatives.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

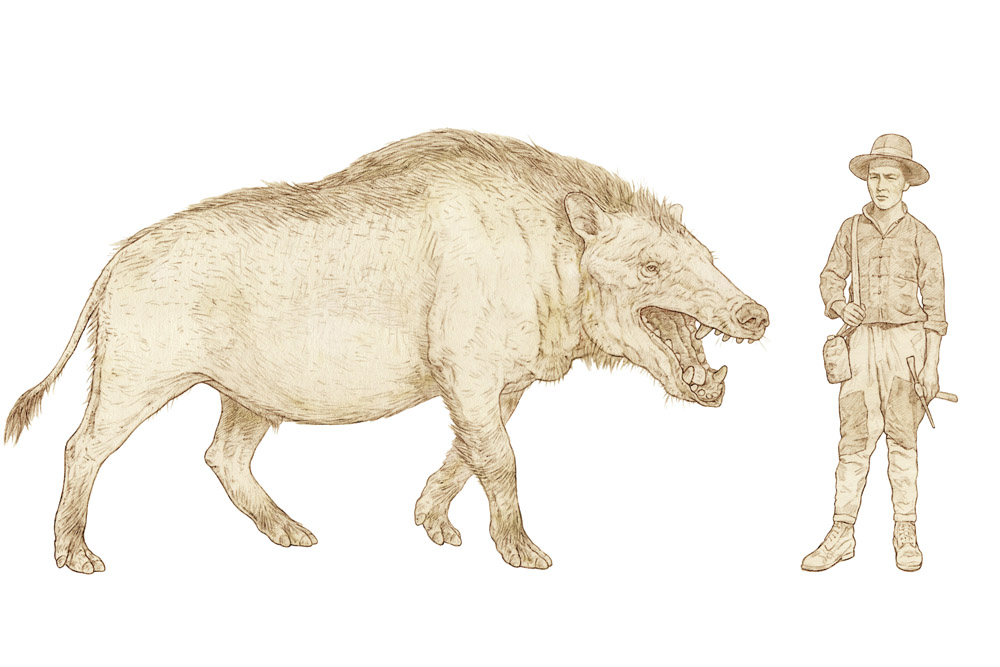

Andrewsarchus mongoliensis illustration

Andrewsarchus mongoliensis, a prehistoric cousin of whales, is shown in this artist’s reconstruction. Andrewsarchus may have been as large as 12 feet long and 6 feet tall at the shoulders, making it the largest meat-eating land mammal ever. The only fossil specimen of Andrewsarchus ever found—its skull—was discovered in 1923 by Kan Chuen Pao (shown here for scale) on an American Museum of Natural History expedition in Inner Mongolia.

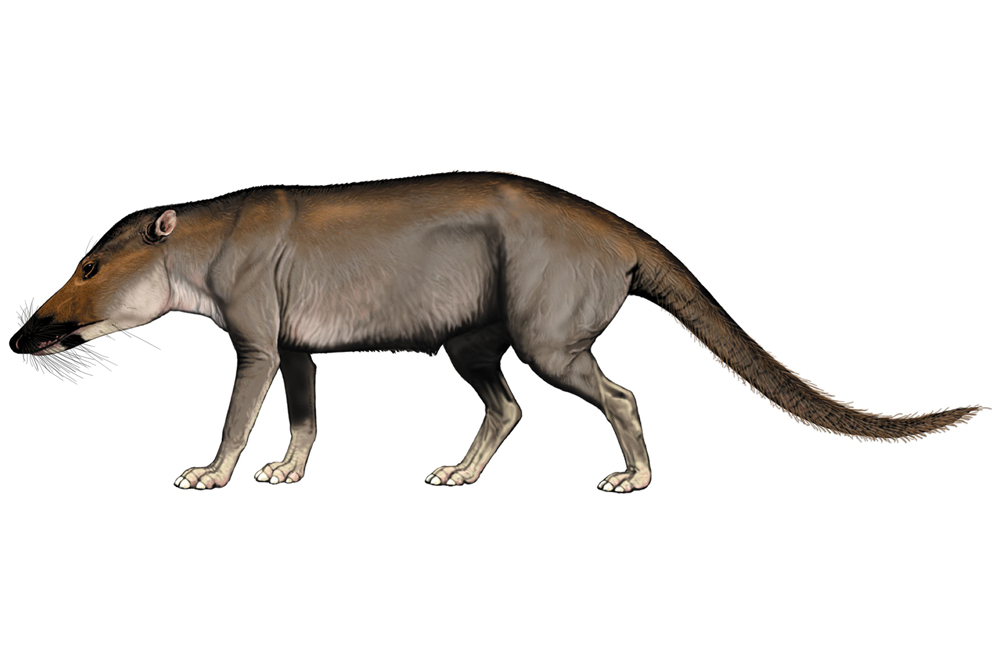

Pakicetus attocki

The earliest-known member of the modern whale lineage is Pakicetus attocki, seen in this artist’s reconstruction. Pakicetus lived on the margins of a large shallow ocean about 50 million years ago. Chemical information from the teeth of some of these wolf-sized meat-eaters shows that they ate fish.

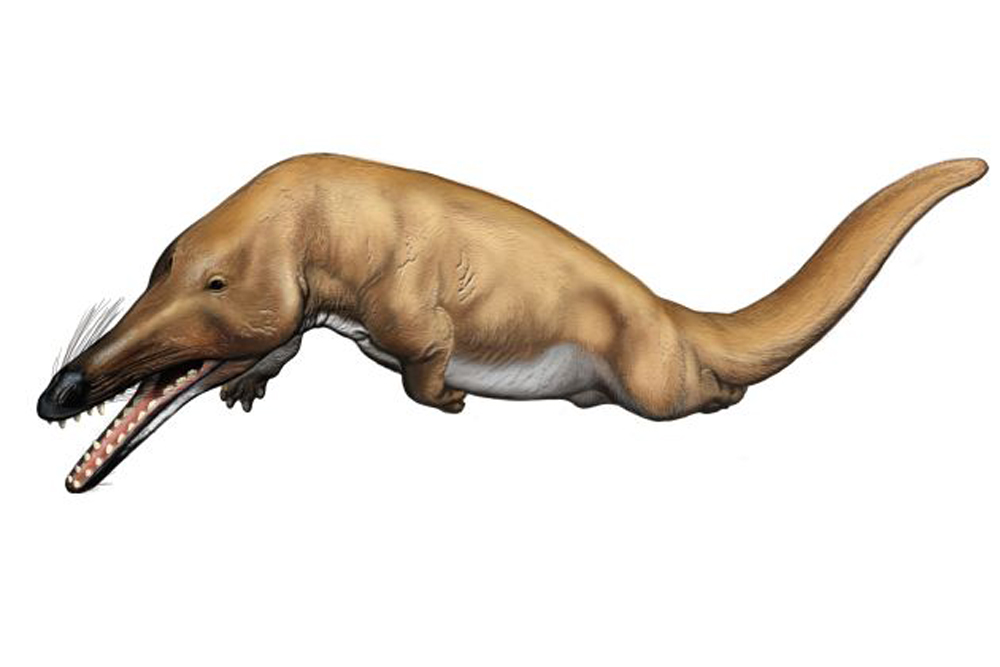

Kutchicetus minimus

The early whale shown in this artist’s reconstruction, Kutchicetus minimus, had a small, otter-like skeleton and lived between about 43 and 46 million years ago in tropical seas. How did Kutchicetus swim? Its hind legs are smaller than those of earlier whales and probably had little to do with propulsion. Its long tail might have helped, although there is no evidence of tail flukes as seen in living whales. Kutchicetus probably had blubber, an adaptation that insulated and streamlined the body, which in turn aided swimming.

South Pacific treasure house

Visitors can enter a pātaka taonga (storehouse of treasures) that contains valuables ranging from gorgeous adornments to deadly weapons, from places such as New Zealand and Fiji. Only chiefs and others with prestige and authority owned such status symbols. The items in a pātaka would usually be made of bone, wood, or stone. Those formed from whale bone are especially precious.