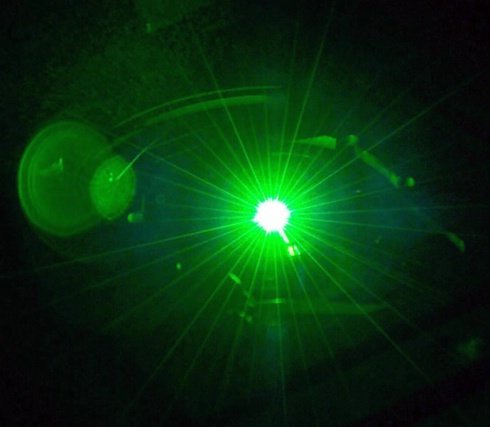

This Is the Purest Beam of Light in the World

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A team of scientists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) has made the purest laser in the world.

The device, built to be portable enough for use in space, produces a beam of laser light that changes less over time than any other laser ever created. Under normal circumstances, temperature changes and other environmental factors cause laser beams to wiggle between wavelengths. Researchers call that wiggle "linewidth" and measure it in hertz, or cycles per second. Other high-end lasers typically achieve linewidths between 1,000 and 10,000 hertz. This laser has a linewidth of just 20 hertz.

To achieve that extreme purity, the researchers used 6.6 feet (2 meters) of optical fibers that were already known to produce laser light with very low linewidth. And then they improved the linewidth even more by having the laser constantly check its current wavelength against its past wavelength and correct any errors that cropped up. [6 Cool Underground Science Labs]

This is a big deal, the researchers said, because high linewidth is one of the sources of error in precision devices that rely on beams of laser light. An atomic clock or a gravitational-wave detector with a high-linewidth laser can't produce as good a signal as a low-linewidth version, muddling the data the device produces.

In a paper published today (Jan. 31) in the journal Optica, the researchers wrote that their laser device is already "compact" and "portable." But they're trying to miniaturize it further, they said in a statement.

One possible use they imagine? Gravitational-wave detectors based in space.

Gravitational-wave detectors sense the impact of massive, faraway events on space-time. When two black holes collide, for example, the resulting shock wave causes space to ripple like a pool of water struck with a stone. The Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) first detected these ripples in 2015 in a Nobel Prize-winning experiment that relied on carefully monitoring laser beams. When those beams changed shape, it was evidence that spacetime itself had been perturbed.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Researchers plan to build bigger, more-precise gravitational-wave detectors in orbit. And these MIT scientists think their lasers would be perfect for the task.

- The 9 Biggest Unsolved Mysteries in Physics

- The Large Numbers That Define the Universe

- Twisted Physics: 7 Mind-Blowing Findings

Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus