Code-Name 'Corona': Earliest Spy-Satellite Images Reveal Secrets of Ancient Middle East

When the United States launched its first secret "spy satellites," in the 1960s, the onboard cameras captured never-before-seen views of Earth's surface. Though once used for uncovering critical military secrets of U.S. foes, those now-declassified images recently found a new purpose: providing archaeologists with an important window into the past.

Scientists are using the satellites' decades-old photos of the Middle East to reconstruct archaeological sites that disappeared many years ago, erased by urbanization, agricultural expansion and industrial growth, researchers reported in December at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU).

By comparing these "spy" images to more-recent satellite photos, scientists can track settlements and historically important sites that have since been obscured or destroyed, the researchers explained at AGU. [Mind-Controlled Cats? 6 Incredible Spy Technologies]

And a free online application that corrects image distortion in the satellites' camera system makes analyzing these photos easier than ever, researcher Jackson Cothren, a professor with the department of geosciences at the University of Arkansas and a leader of the image-correction project, told Live Science.

Spies in the skies

Code-named "Corona," the satellite initiative took shape in the late 1950s, helmed by experts with the U.S. Air Force and the CIA, according to a CIA archive.

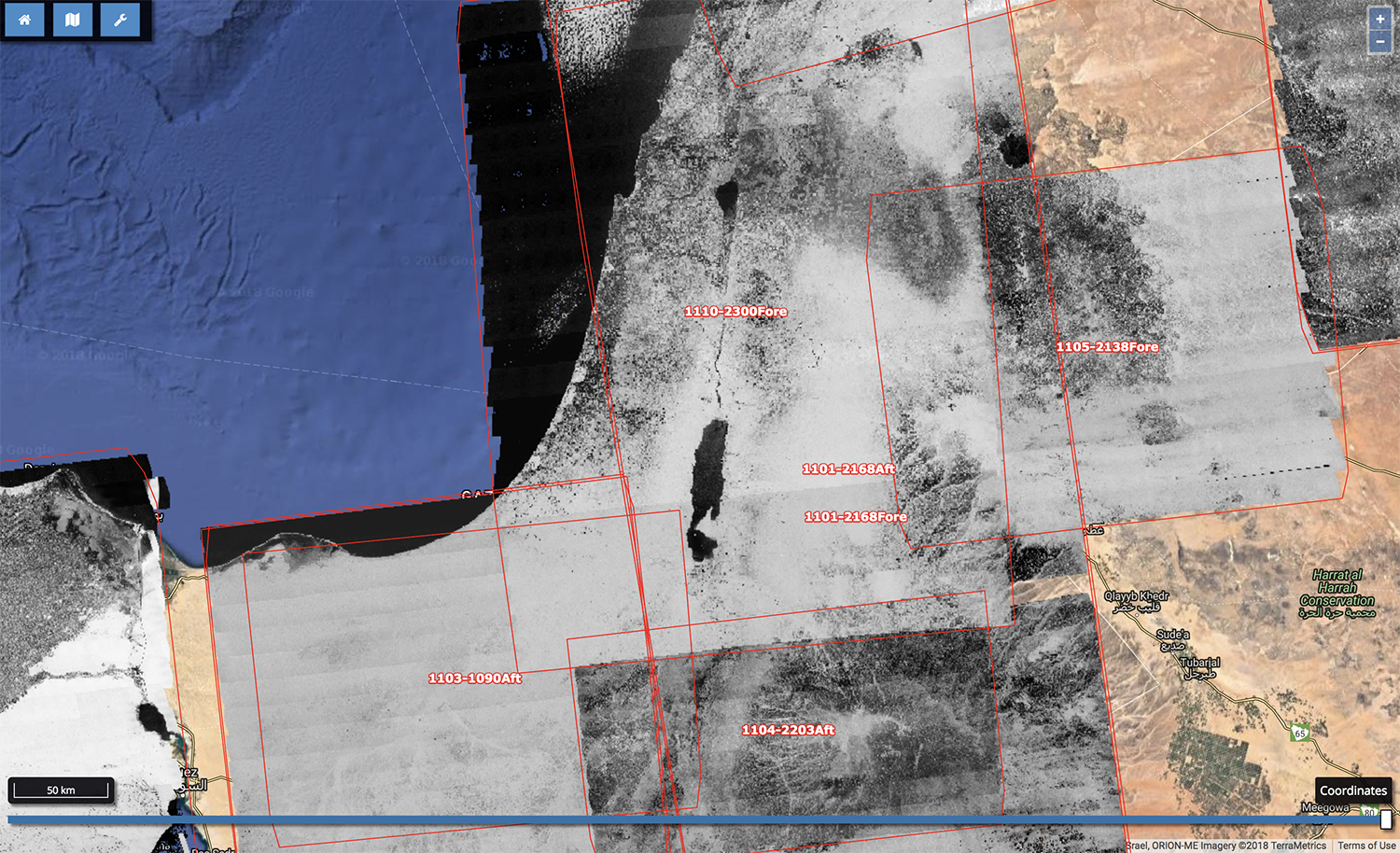

Corona captured images of nearly the entire globe, but its main objective was photographic surveillance — primarily of the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China. From 1960 to 1972, Corona shot individual images that each covered a ground area of 10 miles by 120 miles (16 km by 193 km) on average. The project collected more than 800,000 photos that President Bill Clinton declassified in 1995, making the images available to the public through the U.S. Geological Survey, the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) reported.

However, there was another wrinkle that prevented easy viewing of the declassified photos. Because Corona's stereo panoramic cameras captured large areas at very high resolution on long strips of film, correcting spatial distortion in the photos in order to map them was very challenging; the resulting images resembled "sort of a huge bow tie on the ground," Cothren said. And no commercially available software could efficiently address the distortion, the researchers said at AGU.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To accomplish that task, they developed a free web-based tool that they dubbed "Sunspot," which anyone can use to upload and adjust Corona images. Sunspot then produces corrected files, which can be plugged into mapping software, Cothren said. The researchers used Sunspot to build the Corona Atlas, a database of corrected Corona images available for scientific use.

Corona's images of the Middle East were of particular interest to archaeologists, because of how dramatically the historically important region has changed since the 1960s, according to Cothren. Thanks to Corona Atlas, scientists have been able to rediscover ancient settlements that had been "lost"; since the project's inception, the number of mapped archaeological sites in the Middle East has increased by about 100 times, Cothren said.

"We've been able to map tens of thousands of sites — Bronze Age, Roman age. And we've classified them in a way that helps landscape archaeologists understand the distribution of populations over time," he added.

Corrected Corona images can also be used to track landscape shifts caused by climate change, such as drainage patterns in the Arctic shaped by melting permafrost, Emma Menio, a researcher and doctoral candidate in geology at the University of Arkansas, told Live Science.

"We've seen this amplification of Arctic warming over the last 30 to 40 years," Menio said. "Having historical imagery like Corona — and other imagery from that time period — allows us to create a baseline so that we can look at the landscape before it started rapidly changing."

- Flying Saucers to Mind Control: 22 Declassified Military & CIA Secrets

- Photos: Top-Secret, Cold War-Era Military Base in Greenland

- The 10 Most Outrageous Military Experiments

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works. She is the author of the book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control," published by Hopkins Press.