Watch These Ghostly Faces Suddenly Reappear in the World's Oldest Photos

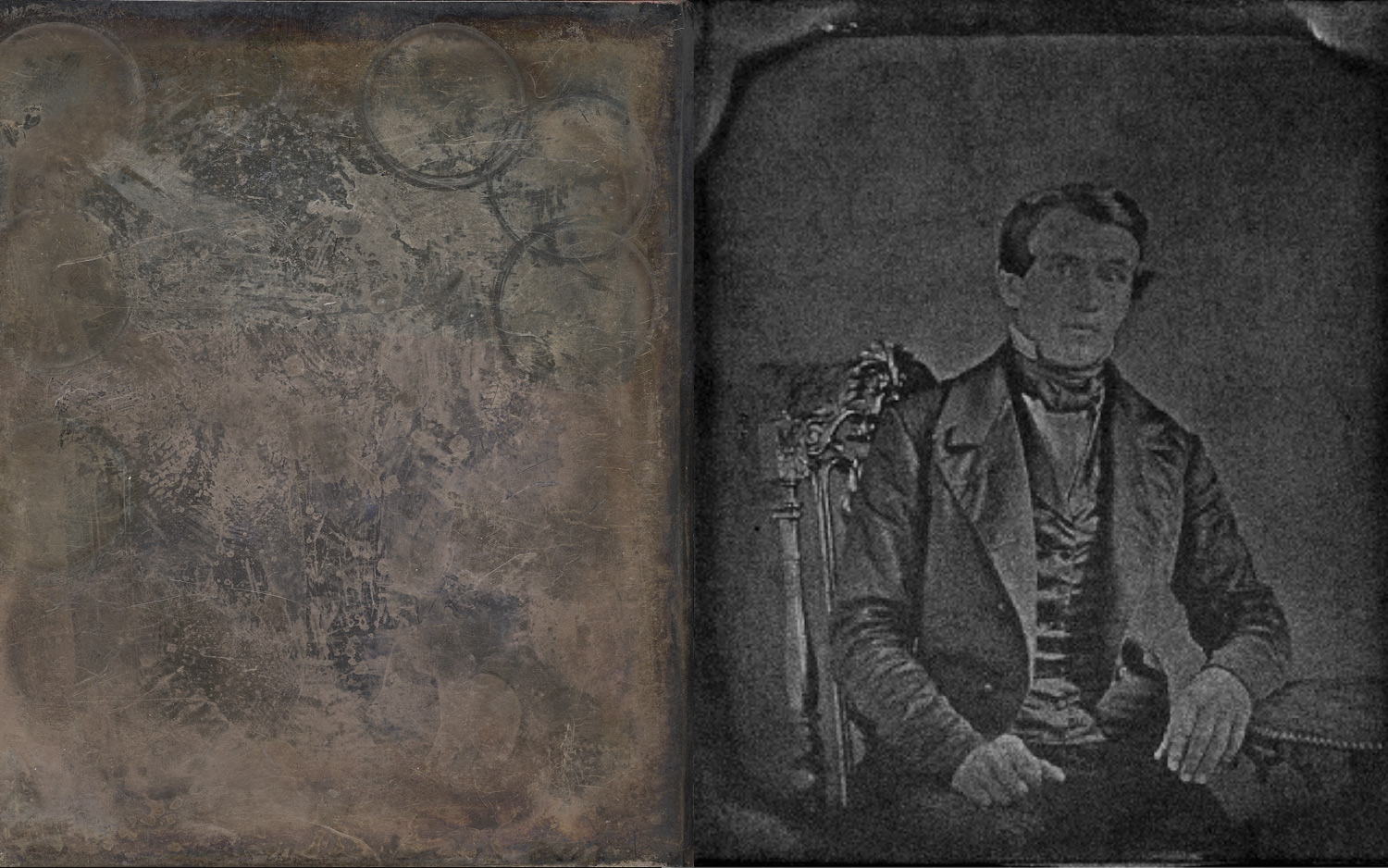

Like ghostly apparitions, faces that have long since disappeared from some of the world's oldest photographs have suddenly reappeared in all their eerie detail.

No, those photographs aren't possessed by the long-lost souls in the pictures. Instead, they've gotten a second life, thanks to a new technique.

By examining the mercury distribution on an old type of photo — known as a daguerreotype — researchers can now digitally recreate the original image that lies beneath the discolored and decaying picture, a new study finds. [19 of the World's Oldest Photos Reveal a Rare Side of History]

"The image is totally unexpected because you don’t see it on the plate at all. It's hidden behind time," study lead researcher Madalena Kozachuk, a doctoral student of chemistry at Western University in Ontario, Canada, said in a statement. "But then we see it and we can see such fine details: the eyes, the folds of the clothing, the detailed embroidered patterns of the table cloth."

Kozachuk reached out to the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa, Ontario, which asked if she wanted to study two corroded daguerreotypes — the earliest form of photography that captured images on silver plates.

Daguerreotypes were invented by Louis Daguerre in 1839, and the two images Kozachuk studied are likely from as early as 1850, although it's unclear who is in each photo. One, of a woman, was purchased at a garage sale, but it's anyone's guess where the image of the man originated, she told Live Science.

These roughly 3-inch-long (7.5 centimeters) daguerreotypes were likely created in either Europe or the United States, Kozachuk noted. But, no matter where they were made, the daguerreotypes' one-of-a-kind recipe allowed Kozachuk and her colleagues to recreate it digitally by using a synchrotron, a type of particle accelerator that acts as a light source.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Early photographers made daguerreotypes by using highly polished silver-coated copper plates that, when exposed to iodine vapour, made the plate light sensitive. Subjects — in this case, the man and the woman — would pose, standing still for 2 to 3 minutes, which allowed the image to imprint sufficiently on the plate. This image could then be developed as a photograph by exposing it to heated mercury vapor which bound to the surface in a light-sensitive manner, followed by treatment with a sodium thiosulfate solution to remove the excess iodide. The images were then covered with glass plates for preservation.

But, over time, the silver plates used in the daguerreotypes tarnished. In previously published research, Kozachuk and her colleagues determined the chemical composition of this tarnish and how it changed over time, as well as the chemical properties of cleaning products used on the daguerreotypes' glass covers, said study co-researcher Ian Coulthard, a senior scientist at Canadian Light Source.

In the new study, the researchers used rapid-scanning micro-X-ray fluorescence imaging on the silver plates to reveal how the mercury was distributed on them. They performed the technique at the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source. The diameter of the X-ray beam used to analyze the daguerreotypes was smaller than the thickness of a human hair, and it took about 8 hours to scan each image.

"Even though the surface is tarnished, those image particles remain intact," study co-researcher Tsun-Kong (T.K.) Sham, Western's Canada Research Chair in Materials and Synchrotron Radiation, said in the statement. "By looking at the mercury, we can retrieve the image in great detail."

Kozachuk noted that the images are still corroded, but the technique allows them to digitally recreate the original image on a computer. "We're not actually altering the daguerreotype itself," she told Live Science. "It goes in and out of the instrument looking exactly the same." [11 Hidden Secrets in Famous Works of Art]

The results were fantastic, she added.

"We really had no expectations going in and we had no idea of the level of resolution we would be able to achieve," Kozachuk said. "The first image we saw was of the woman's face. I think I squealed. It was extremely exciting."

The new technique may help conservators digitally recreate old, corroded daguerreotypes whose images are hiding beneath a layer of tarnish.

The study was published online June 22 in the journal Scientific Reports.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus