Dramatic Video Captures Moment Towering Iceberg Splits from Greenland Glacier

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

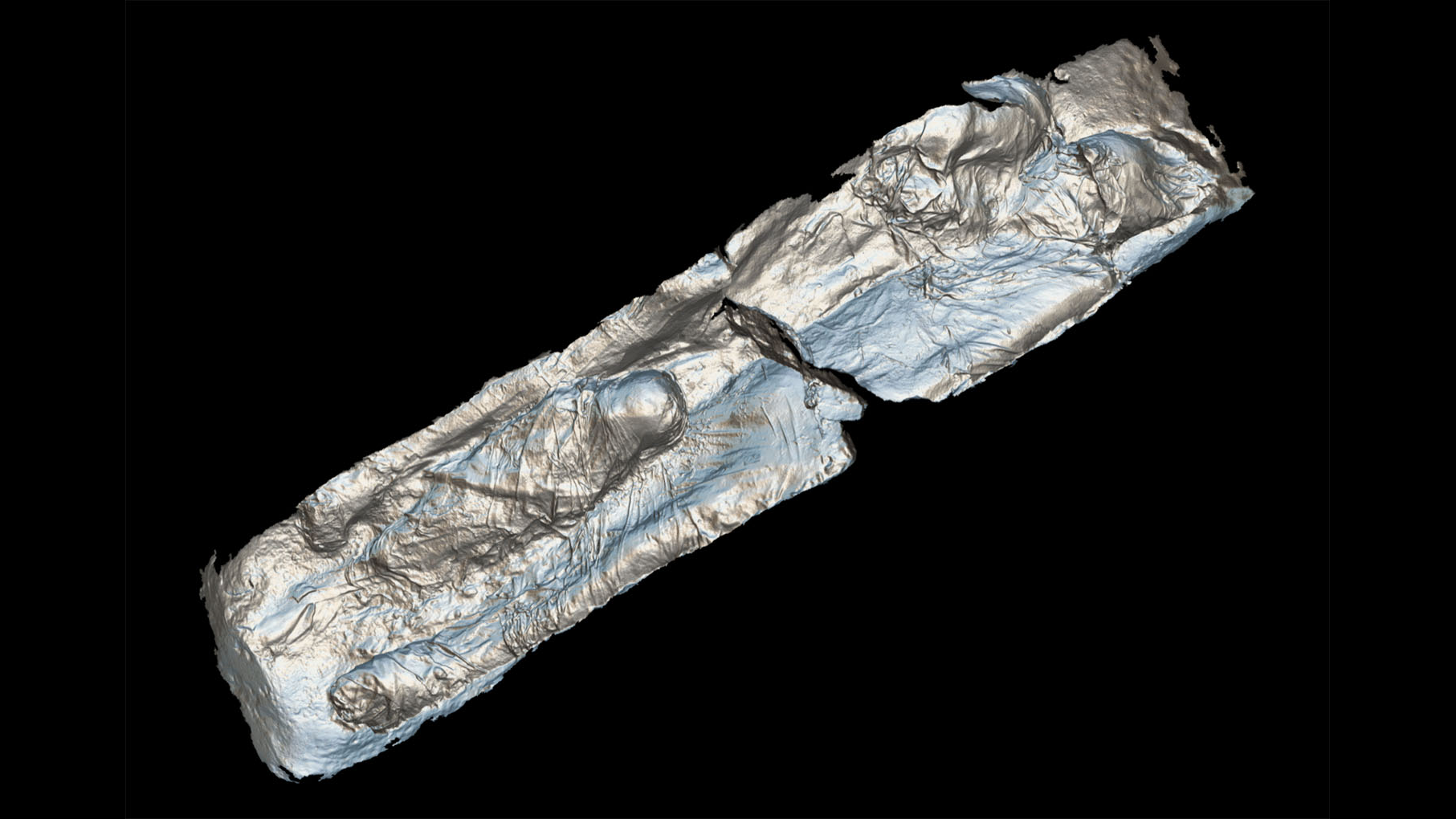

The event, which began at 11:30 p.m. local time on June 22, unfolded over 30 minutes, but the footage is sped up so the calving happens in just 90 seconds, according to a statement released by the researchers. The video shows a wide, flattened iceberg parting from the glacier, and so-called pinnacle bergs — tall, thin icebergs — detach from the larger mass of floating ice and invert in the water, the researchers reported.

While it's hard to get a sense of scale from the camera's wide-angle view of the separating iceberg, the berg is so big that it could partially cover the island of Manhattan, extending from the lower tip of New York City into Midtown, according to the statement. [Images: Greenland's Gorgeous Glaciers]

When large masses of ice part from glaciers, quantities of water are shunted into the ocean and contribute to sea-level rise. But there is much that scientists have yet to learn about how and why this large-scale breakage happens, which makes it difficult to predict when glaciers will fall apart, and how much that glacier disintegration will affect sea levels over time, David Holland, leader of the research team and a professor at New York University's Courant Institute of Mathematics and NYU Abu Dhabi, told Live Science.

Earth's biggest glaciers are in frozen Antarctica, and their breakup would be catastrophic for sea level rise; the loss of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet would release enough water to raise global sea levels by nearly 10 feet (3 meters). But while there are abundant satellite observations of Antarctica's ice sheets, it's extremely challenging to gather data from the surface of the remote continent, Holland said.

Greenland's glaciers are more accessible, so Holland and his colleagues have spent a decade collecting data and observing glacier behavior in Greenland — and this time they just happened to be perfectly positioned to witness an iceberg splitting away, research team member Denise Holland, the logistics coordinator for NYU's Environmental Fluid Dynamics Laboratory and NYU Abu Dhabi’s Center for Global Sea Level Change, told Live Science.

Denise Holland, who shot the footage of the iceberg's birth, said that the researchers had set up camp on the fjord and were preparing to turn in for the night when they heard "an extended roar" that went on for longer than 5 minutes. The sound hinted that something momentous was underway — something that she had witnessed only twice before in the past decade of working on Greenland's glaciers, she told Live Science.

"We could see puffs of ice as it fractured from one side to the other," she said. "Sometimes you get lucky — you have to be at the right place at the right time."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

What was especially fortuitous about this recording was that it showed the ocean noticeably rising as the ice disintegrated; it also captured important evidence of a glacier's ice breakup patterns "in every conceivable way, in one event," David Holland said.

"We saw tabular, flat icebergs like pancakes. We saw vertical pinnacles, tall and skinny ones, some falling head forward. We saw them crash into tabular bergs and break up. In 20 minutes, we saw grounded ice go into the ocean in a variety of calving styles — we were kind of in awe at how interesting it was, and also in awe of the scientific complexity," he said.

And therein lies the challenge of building computer models that can accurately predict the behavior of massive ice sheets, and the giant icebergs they produce. As this video demonstrated, glaciers can fracture in complicated ways — and scientists' current understanding of how that happens is barely the tip of the iceberg, which hampers attempts to model the impact of glacier breakup on rising seas, David Holland told Live Science.

"It's not the kind of thing you can do in your lab at home. You need real glaciers breaking up, and you need real observations," he said. "You need to observe it to understand it."

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus