What This Optical Illusion Reveals About the Human Brain

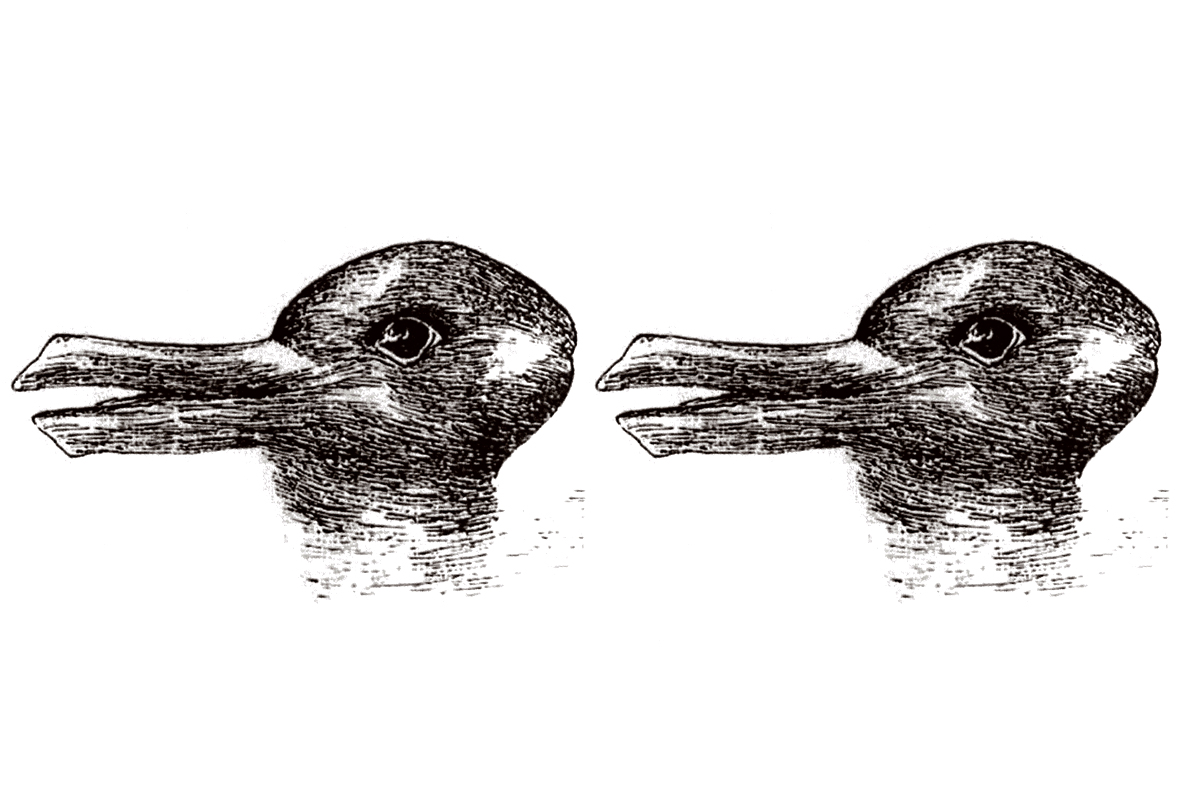

You may be familiar with a 19th-century optical illusion — or, more precisely, "ambiguous image" — of a rabbit that looks like a duck that looks like a rabbit. First published in 1892 by a German humor magazine, the figure was made popular after the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein used it to illustrate two different ways of seeing. You can interpret the image as either a duck or a rabbit, but not both animals at the same time.

It gets trickier if you place two copies of the illusion side by side. You're likely to see two ducks. Or perhaps two rabbits. In fact, about half of people can't see a rabbit and a duck at first glance, according to Kyle Mathewson, a neuroscientist at the University of Alberta, in Canada. To picture one of each species simultaneously, you have to give your brain more information to work with — for example, telling yourself to imagine a duck eating a rabbit.

See it now? Turns out, when it comes to distinguishing between two ways of seeing identical images, context is vital, according to Mathewson's new study.

"Your brain sort of zooms out and can see the big picture when the images are put into context with one another," Mathewson, an assistant professor in the school's department of psychology, said in a statement.

Related: What you see in this famous optical illusion could reveal how old you are

Syntax plays a role, too. The study, which was published online Feb. 5 in the journal Perception, found that simpler phrases — for example, "Imagine a duck beside a rabbit" — didn't have the same effect, namely because they don't tell your brain which figure is the duck and which is the rabbit.

"What we discovered is that you have to come up with a way to disambiguate the scene, to allow the brain to distinguish between two alternatives," Mathewson said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The study also demonstrates the ease with which our brains interpret information with just a few textual or visual cues — a fact we should remain wary of in this age of rampant misinformation, Mathewson said.

"We should all be mindful of that when, for example, we're reading a news story," he added. "We're often interpreting and understanding information the way we want to see it."

Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus