Grand Staircase, Home to Countless Dinosaur Fossils, Could Be Destroyed by Mining (Op-Ed)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

P. David Polly is the president of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology and the Shrock professor of sedimentary geology at Indiana University. Polly contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

President Donald Trump is expected to make a big announcement in Utah this Monday (Dec. 4), where he will detail the government's plan to shrink two of the state's national monuments: Grand Staircase-Escalante and Bears Ears, according to news sources.

The coal industry may welcome this venture, but it could destroy evidence of yet-to-be-discovered dinosaurs and the fossils of ancient mammals, turtles and crocodilians.

There are countless fossils within the nation's national monuments, regions of U.S. public land that are protected by presidential proclamation because of their importance to national heritage. Bears Ears, which received monument status last year, likely holds many key fossils. Grand Staircase-Escalante, designated as a monument more than 20 years ago, has already provided scientists with incredible fossils, including those of triceratops relatives and tyrannosaurs, and there are likely more. Reducing the size of these monuments would be a loss to science and the American public. [5 Fossil Hotspots: National Parks to Visit]

Paleontological treasures

Maps leaked from Utah Gov. Gary Herbert's office suggest that the Trump administration may reduce the monuments by as much as two-thirds their current size, according to The Salt Lake Tribune. Why are they doing it? According to the LA Times, the motivation behind the decision is to open these protected areas to ranching and coal mining.

But that reasoning overlooks an important point: These two monuments were set aside specifically under the American Antiquities Act to protect their paleontological and archaeological resources from damage by mining and other mineral extraction. Both monuments protect exquisite fossil sequences that tell us about crucial intervals in the history of our planet.

Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument was established in 1996, largely because proposed mining activity on Bureau of Land Management (BLM) property threatened the remote highland area known as the Kaiparowits Plateau, a region rich with fossil treasures. About 28 billion commercially extractable tons of coal lie beneath its surface, formed in the same ancient swamps that were home to animals that lived during the Cretaceous, a period lasting from 145 million to 65 million years ago.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Mining on national monuments is illegal, but the government often grants mining leases on other types of federal land. Indeed, mining on public lands can be especially profitable because there are no private, surface landowners to compensate for the access to the land.

In the 1990s, the coal mining company Andalex Resources was planning to open a mine twice the size of Manhattan on the Kaiparowits Plateau. But the plateau had already become an important site for science because of the spectacular fossils of Cretaceous-period mammals discovered there by Richard Cifelli, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Oklahoma, and Jeff Eaton, then an assistant curator of paleontology at the Museum of Northern Arizona, who is now retired. Using screen washing, a technique similar to panning for gold, these paleontologists discovered minute fossils in the coal-bearing rocks.

These fossils included those of a tiny creature known as Paranyctoides — the oldest placental known at the time — that filled a critical gap in scientists' understanding of the origin of mammals, Cifelli explained in a 1990 study published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. (A placental animal is one that, like humans, gives birth to fully viable young, in contrast with marsupials that nurse their young in pouches or monotremes, such as the platypus, that lay eggs.)

The importance of these fossils — and the prospect of an even richer paleontological record that, unlike coal, was unique to the Grand Staircase area — motivated the creation of the monument. [Album: Discovering a Duck-Billed Dino Baby]

Fossil wonderland

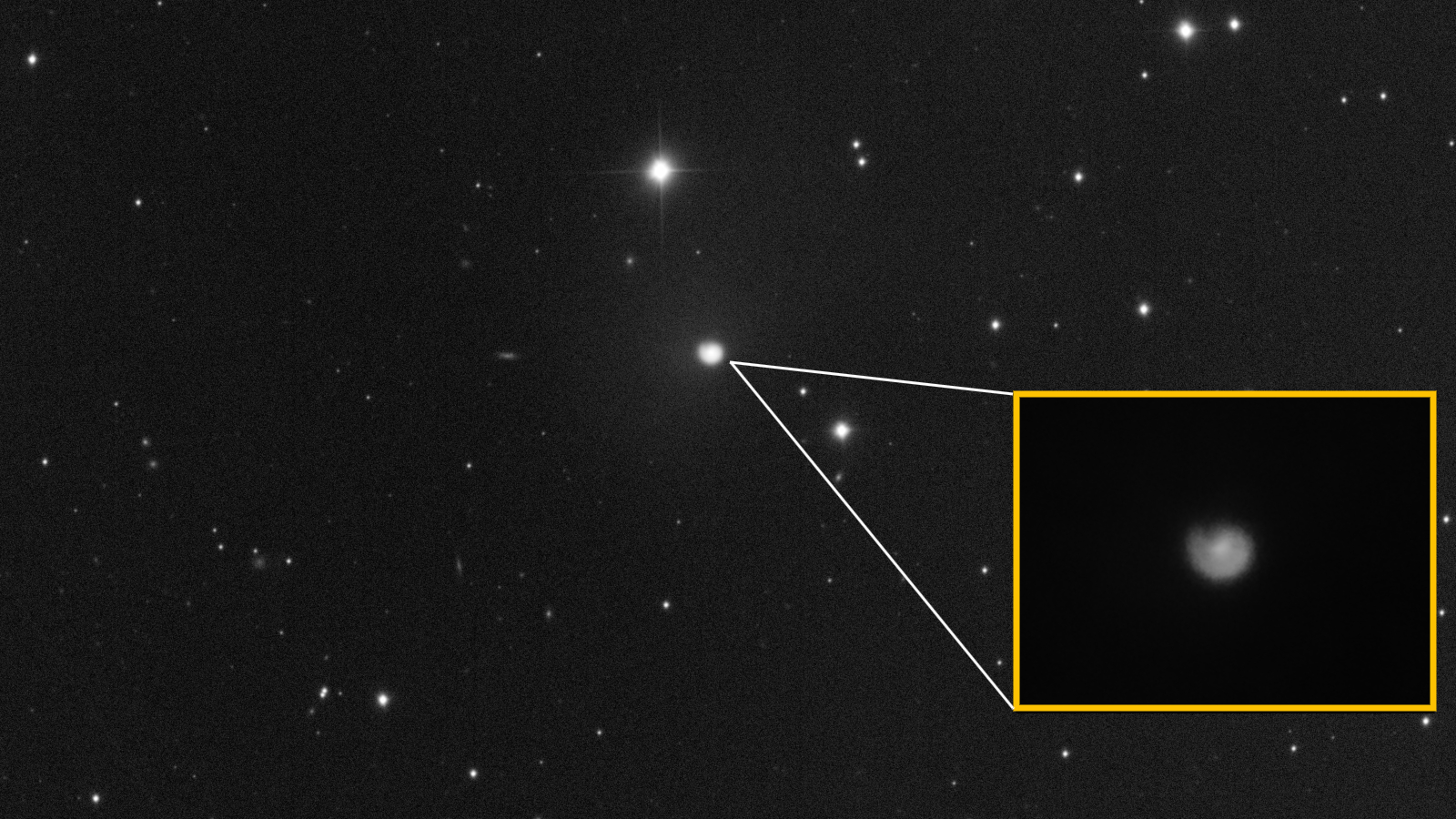

The monument promised to be "one of the best and most continuous records of Late Cretaceous terrestrial life in the world," according to a 1996 proclamation from then-President Bill Clinton. But the scale of the discoveries since then is so large that they would have inconceivable at the time. Within the monument, scientists and amateurs have discovered more than 3,000 scientifically important sites (places with intact, identifiable fossils in their original geologic context), collected hundreds of thousands of fossil specimens and uncovered nearly 40 previously unknown animal species, including 13 new kinds of dinosaur.

Last month, I visited Grand Staircase as president of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology to see this incredible site for myself. As a paleontologist, I have worked in the Cretaceous-age rocks of Hell Creek in Montana and Big Bend National Park in Texas, as well as in central Kazakhstan and the Gobi Desert in Mongolia, but I was totally blown away by the Kaiparowits Plateau's wealth of fossils. Prospecting for fossils there is accessible in a matter of steps rather than miles.

The Kaiparowits Plateau is exceptionally rich in fossils of mammals, turtles, crocodiles, lizards and dinosaurs. Moreover, its status as a monument provides resources for science — notably, coordination from the BLM monument paleontologist Alan Titus. Hundreds of paleontologists from museums and universities around the country have organized their field research through Titus' office. For example, in 2009, a field crew led by Andrew Farke, a paleontologist at the Raymond M. Alf Museum of Paleontology in Claremont, California, discovered a baby duck-billed dinosaur, Parasaurolophus, that revealed that the bony crests on the heads of these remarkable creatures grew larger as they got older, according to Farke's 2013 study in the journal PeerJ.

In 2006, a newfound short-skulled tyrannosaur called Teratophoneus curriei was unearthed by a collaborative group from Carthage College in Kenosha, Wisconsin; the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science in Albuquerque; and Brigham Young University in Utah. Teratophoneus filled a gap in the evolutionary history of its younger cousin Tyrannosaurus rex, according to the researchers' 2011 study in the journal Naturwissenschaften (now called The Science of Nature).

More of these remarkable animals have been found since, including a virtually complete skeleton of Teratophoneus that was airlifted from a nearly inaccessible part of the Kaiparowits Plateau in October of this year. Another Grand Staircase paleontologist from Virginia Tech University, Michelle Stocker, told me, "We're never done finding new fossils and filling in those gaps." Without the monument, much of this work would not have happened, and it would have been a greater challenge for researchers across the country to coordinate with one another. [Top 10 Most Visited National Parks]

Because the land and its fossils remain the property of all Americans, federal law stipulates that the fossils themselves be placed in an approved public research repository, which will make the fossils available to those who want to see them.

"Every fossil stored in a museum is a little piece of life frozen in time," said John Long, former president of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. The preservation of the fossils and their sites is critical to scientific progress because paleontologists often revisit them with new questions and techniques. As Anjali Goswami, a paleontologist at the Natural History Museum in London, explained, "New technology has made it possible to extract information from fossils and fossil sites that would have been impossible even 10 years ago."

But not everyone sees the scientific potential of these monuments.

"I'm approving the recommendation for you, Orrin," Trump told Utah Sen. Orrin Hatch, according to The Salt Lake Tribune. But neither the monuments nor the fossils are Trump's to give or Hatch's to take. They belong to all Americans as part of the U.S. public land system. The multiple-use principle used to manage federal public lands means that most of the system's 640 million acres (260 million hectares) are already open to ranching and coal mining, including the strip mining and gas fracking in the Thunder Basin National Grassland of Wyoming.

Just a few public land areas are set aside to protect unusually delicate or important assets such as wildlife, archaeology, landscapes and scientifically important resources. The paleontological science at Grand Staircase-Escalante and Bears Ears was one of the primary justifications for turning these wilderness lands into national monuments so that coal mining, petroleum extraction and other damaging activities would not ruin the scientific value they provide to us all.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus