54-Million-Year-Old Baby Sea Turtle Had Built-In Sunscreen

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

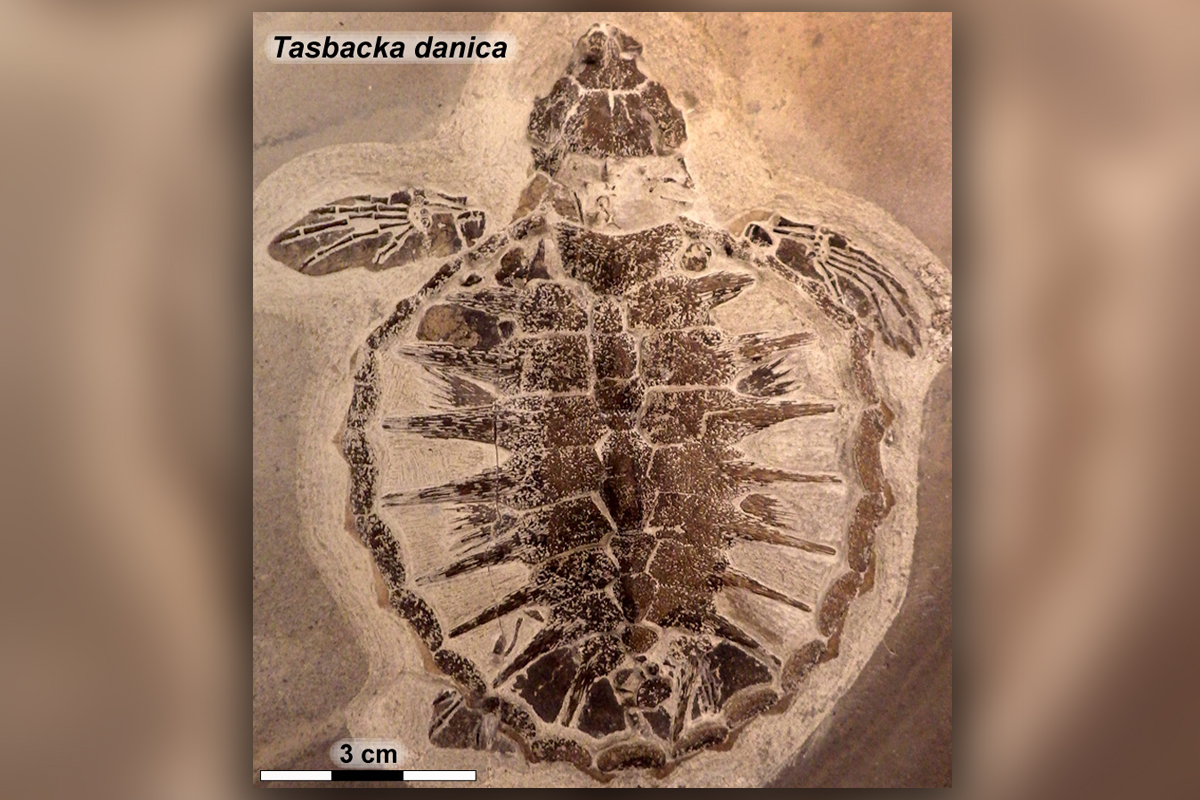

An extraordinarily well-preserved fossil of a baby sea turtle that lived 54 million years ago contains traces of dark pigments that would have acted as built-in sunscreen, protecting the animal from the sun's harmful ultraviolet (UV) radiation.

The specimen, which is among the best-preserved fossils of sea turtles in the world, includes soft tissue, and analysis identified molecules linked to color, muscle contraction and oxygen transport in the blood, researchers reported in a new study.

One molecule in particular — eumelanin, a pigment linked to dark skin color in humans — hinted that the ancient turtle's shell contained dark colors, perhaps in patterns such as those found in sea turtles alive today, the study authors wrote. [Image Gallery: 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts]

Found in 2008 entombed in fine-grain limestone in a marine deposit in Denmark, the fossil is very small — about 3 inches (74 millimeters) long, and many of the bones retain their original shape in three dimensions. The reason the fossil is in such good condition is likely that the turtle's remains were trapped within a hard, rocky mass of sediment very early in the fossilization process, the study's lead author, Johan Lindgren, a senior lecturer with the Department of Geology at Lund University in Sweden, told Live Science in an email.

After much of the fossil mineralized, protecting remnants of soft tissue, the absence of extreme heat or cold would have prevented any remaining soft tissue from degrading further, Lindgren explained.

The scientists evaluated five samples of soft tissue from a sublayer in the turtle's shoulder area, which was revealed during a second stage of fossil cleaning and preparation in 2013. When the researchers probed the tissue samples, they noted "a dark, well-defined film" containing structures that were carbon-rich, and which may have held organic compounds, they reported in the study.

The researchers analyzed the film using a combination of imaging and chemical techniques, which allowed them to identify molecules and determine their precise locations within the fossil — specifically, in organic material that once made up the turtle's skin and shell, Lindgren told Live Science.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Molecules of eumelanin revealed to the scientists that the turtles were pigmented with dark patches, much like the dark patterns seen on the backs of modern sea turtles, the study authors wrote. Patterns with dark coloration are known to protect sea turtles from UV rays and also help young turtles retain heat, which can enable them to grow faster. This biological feature is known as adaptive melanism — coloration that improves the turtles' chances for survival — and the researchers' findings suggest that this adaptation may have emerged in the turtle lineage as early as 54 million years ago, according to the study.

Scientists have examined fossilized plants and animals for centuries, yet there is still much to be discovered about how living organisms are preserved for millions of years, and how much of their biological makeup may be retained after fossilization, Lindgren told Live Science.

"Despite many years of research, we still have an incomplete understanding of what can be retained in the fossil record and exactly how the fossilization process works," Lindgren said.

The findings were published online Oct. 17 in the journal Nature: Scientific Reports.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus