What Are Saturn's Rings?

Saturn's rings are one of the most striking features of the solar system. They encircle the sixth planet from the sun in bizarre configurations, each thousands of miles wide but just a few dozen feet thick.

So what are they?

The rings are mostly ice with a little bit of rock mixed in. Scientists have a better grasp of their dynamics than ever before, thanks to the Cassini spacecraft, which ends its mission on Friday (Sept. 15) with a plunge into Saturn's atmosphere, after 13 years of orbiting the planet. Over that time, Cassini sent unprecedented photographs of Saturn's rings earthward, giving researchers a close look at some of the odd structures found amid the ice.

The rings were first discovered in 1610 by Galileo Galilei, who could just make them out by telescope. Today, scientists have identified seven separate rings, each of which have a letter name. Confusingly, the letters are a bit scrambled because the rings got their names in the order they were discovered, not in the order they are from their planet. The closest to Saturn is the faint D ring, followed by the three brightest and largest rings, C, B and A. The F ring circles just outside the A ring, followed by ring G and, finally, ring E.

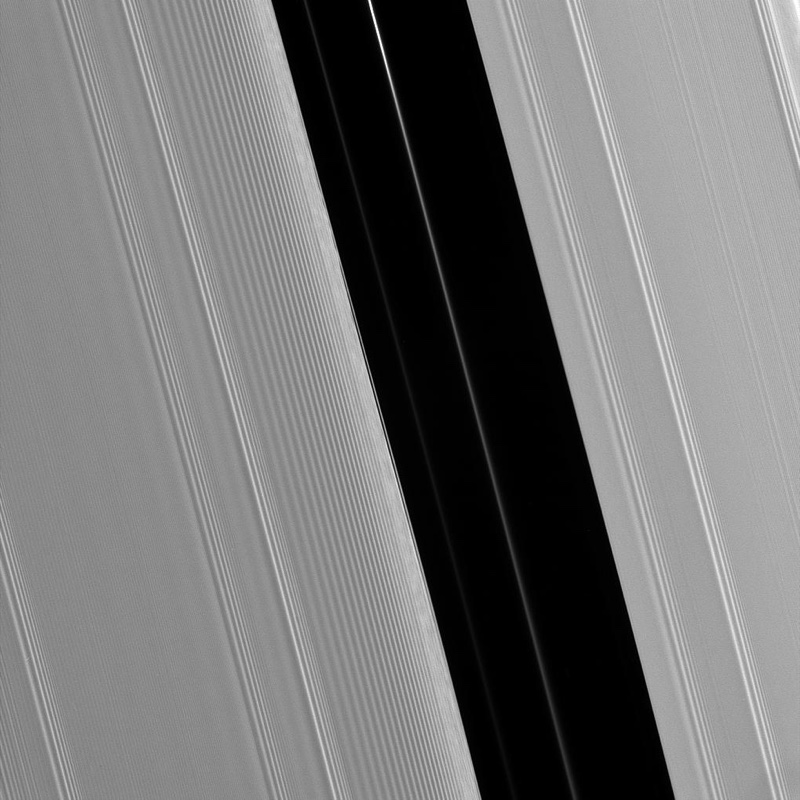

Zooming in, the rings are made of very fine particles, some smaller than a grain of sand, interspersed with occasional mountain-size chunks of ice. Scientists suspect that many of the particles are bits of broken-up comets or dead moons, though their exact origin and formation remain a mystery. The Cassini mission was able to trace the source of some of these particles to the planet's moon Enceladus, which vents gas and ice into space. Other portions of rings appear to originate from debris from some of Saturn's inner moons, which also play a role in gravitationally shaping the rings. These moons orbit within Saturn's rings, and as they do, they help divide the rings and constrain their width. The inner edge of the A ring, for example, is delineated by the gravitational influence of the moon Mimas, which helps form the Cassini Gap.

The rings are very chilly. In 2004, the Cassini spacecraft measured them on their unlit side at between minus 264.1 degrees and minus 333.4 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 163 degrees and minus 203 degrees Celsius). They're not nearly as rainbow-colored as some astronomical images make them out to be: Upping the contrast can make for dramatic portraits, and some images use color to convey information about temperature or density, but natural color images show a palate ranging from white to light yellow to a slightly pink brown.

Each ring has a different density, from the packed-tight ring B to the misty faintness of ring G. They're very dynamic, and thanks to the interactions of the particles within them, the rings are far from smooth. Mimas is just one example of a "shepherd" moon within the rings. Another moon, Pan, sweeps through the 200-mile-wide (325 km) Encke Gap in the A ring. This gap in the A ring is sculpted into a scallop shape by the 12-mile-wide (20 km) moon.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Some rings also contain skewed features called "propellers," which are little proto-gaps caused by tiny moonlets without the gravitational influence to open a crack like the Encke or Cassini gaps. Another strange feature of the rings are its "spokes," which look like wedges or lines that orbit with the rings. According to NASA's Cassini mission page, these spokes are conglomerations of itsy-bitsy ice particles that levitate above the ring's surface via electrostatic charge. They're temporary, and were discovered by the Cassini mission in 2005.

Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.