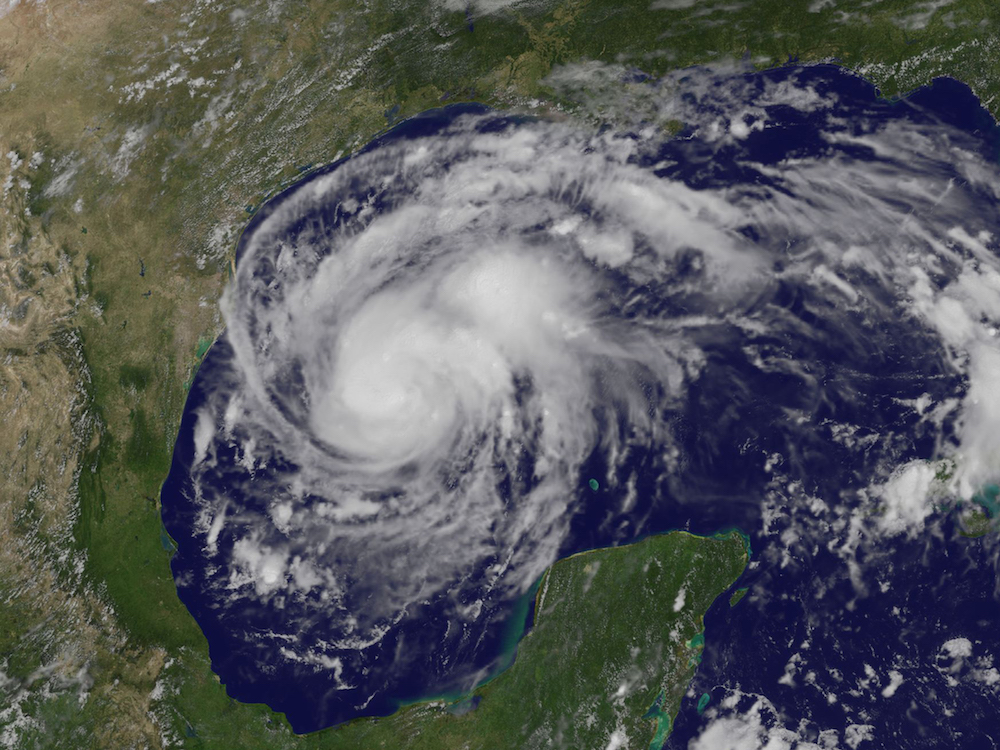

Hurricane Harvey Threatens Texas with 'Devastating' Floods

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Texans from Houston to Corpus Christi are bracing for a wallop from Hurricane Harvey, which is rapidly intensifying in the Gulf of Mexico before its expected landfall late Friday or early Saturday.

Harvey will be the first hurricane to make landfall in Texas in nine years (and could be the first major hurricane to hit the U.S. since 2005). That long period of calm has experts worried that many people will be unprepared for the storm.

"There's a lot of uncertainty" in the forecast, "but you have to be aware that there's a really real risk that this could be a devastating event," Steven Bowen, director of impact forecasting at the reinsurance company at Aon Benfield, told Live Science. [Hurricane Season 2017 Guide]

The most worrying threat from the storm is the staggering amount of rain it is expected to dump on the area, Bowen and others said. This will put lives and property at risk in a region that has seen explosive growth in recent years and where only 15 percent of homes have flood insurance even in the most well-covered areas.

Birth of a storm

Harvey formed last week in the Atlantic Ocean before being done in by shearing winds as it wound its way through the Caribbean. But after its remnants crossed Mexico's Yucatan Peninsula, the storm pulled itself back together with the help of ample warm water and favorable winds.

Forecasts predicted that Harvey would rapidly intensify overnight, from Wednesday to Thursday, though the speed with which it did so was still surprising, said Matt Lanza, a Houston-based meteorologist in the energy industry and a contributor to Space City Weather, a site dedicated to Houston weather.

Harvey became a hurricane Thursday afternoon and could continue to beef up into a major storm according to the National Hurricane Center in Miami. A major hurricane is defined as a Category 3 or higher on the Saffir-Simpson scale, or a storm that has winds of 111 mph (179 km/h) or higher.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Those winds and the storm surge they whip up will pack a punch along the coast, particularly close to the eye at the center of the storm, where the strongest winds are found, experts said. But the major concern with Harvey is the torrential rain it is expected to unleash. That rain comes courtesy of the ample moisture supplied by the Gulf of Mexico and the likelihood that the storm will stall out after it makes landfall, dumping rain continuously on the same area, several meteorologists said.

"There's just a lot to be concerned about with this storm," Bowen said. [A History of Destruction: 8 Great Hurricanes]

Heavy rains

The NHC forecasts rains of 12 to 20 inches (30 to 51 centimeters) over a widespread area of coastal and inland Texas through next Wednesday, with some spots seeing up to 30 inches (76 cm).

"It's going to be one hell of a rainmaker," said Phil Klotzbach, a hurricane researcher at Colorado State University.

All that rain, particularly if it falls in heavy bursts, could cause significant and potentially deadly flooding.

Houston is no stranger to heavy rains and floods. Several major flash floods driven by thunderstorms in recent years caused billions of dollars in damage, producing dramatic footage of people trapped in their homes and apartment buildings by floodwaters.

"People get nervous now when it rains," Lanza told Live Science, "especially people that were flooded during those events."

But the effects of those flash floods were much more localized than the impact from Harvey is likely to be, Lanza said. Perhaps the most apt comparison, Bowen said, is Tropical Storm Allison, which hit southeast Texas in 2001 and dumped 40 inches (102 cm) of rain in the worst-hit spots. The ensuing floods swamped some 70,000 homes and caused billions of dollars in damage.

"Allison is a four-letter word here," Lanza said. "When you start saying that [name], people really get nervous."

A history of devastation

But a hurricane hasn't hit Texas since 2008, when Ike landed in Galveston, bringing storm surges of 13 to 17 feet (4 to 5.2 meters) in the worst-affected areas. The hurricane, which affected Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi and Florida, in addition to Cuba and parts of the Caribbean, knocked out power to millions and killed 74 people in Texas alone.

"That part of Texas has seen explosive population and exposure growth" since Ike and Allison, Bowen said, meaning there is even more potential for heavy damage now.

Bowen took to Twitter to warn that some flooded areas could be unreachable for weeks as the water slowly recedes, as happened last year when an unnamed storm system dumped more than 2 feet (0.6 m) of rain in some spots around Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Compounding the potential for damage is the low rate of flood insurance coverage in the area. Harris County, where Houston is located, has the highest rates, but even there, they are about 15 percent, Bowen said. In neighboring counties, rates are in the single digits, Bowen said. That means a lot of damaged homes won't be covered.

What parts of the Houston metro area get the worst of the rains and floods will depend on the exact track of the storm and where the heaviest bands of rain occur, Lanza said. The system of bayous that drain the region flow from northwest to southeast and then empty into the gulf. If the heaviest rains fall south of the city, they will flood a smaller area, as they have a shorter distance to head back to the ocean, he said.

But if they fall to the north and west, they will have to flow through the city and could tax the reservoirs meant to hold some of the water back, Lanza said.

"It really is a waiting game, unfortunately," Bowen said.

Original article on Live Science.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus