Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Hidden beneath the world's largest prehistoric stone circle, archaeologists in England have discovered an even older, secret square-shaped megalithic monument.

"Our research has revealed previously unknown megaliths inside the world-famous Avebury stone circle. We have detected and mapped a series of prehistoric standing stones that were subsequently hidden and buried, along with the positions of others likely destroyed during the 17th and 18th centuries," Mark Gillings, academic director and reader in archaeology in the School of Archaeology and Ancient History at the University of Leicester, said in a statement. "Together, these reveal a striking and apparently unique square megalithic monument within the Avebury circles that has the potential to be one of the very earliest structures on this remarkable site."

The new finds are shocking for such an old site, which has been extensively studied by archaeologists since the 1600s. The Avebury site in Wiltshire, southwest England, is one of the most mysterious ancient monuments in the country. The Neolithic monument was built largely between 4,850 and 4,200 years ago, according to English Heritage. Along with Stonehenge, Silbury Hill and Windmill Hill, the newfound monuments may have formed a vast sacred landscape that ancient people used for rituals and communal gatherings whose purpose remains shrouded in mystery.

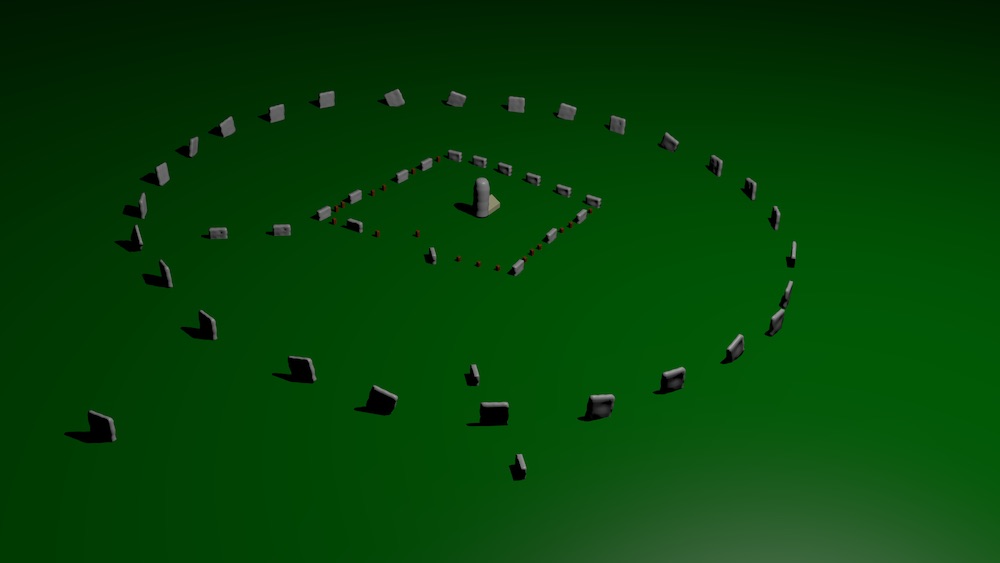

The site of Avebury consists of a vast circular henge — of which all that remains is a 3,270-foot-across (1,000 meters) circular ditch and embankments — and an inner stone circle, which was once composed of nearly 100 massive, upright boulders and two smaller inner stone circles.

In 1939, Alexander Keiller, heir to a marmalade fortune and an amateur archaeologist, noticed that some of the stones in the inner circle seemed to be angular in their alignment. He believed the faint hint of a square may have been the remnants of a medieval cart shed, according to the statement. World War II soon broke out, and Keiller was unable to continue his archaeological surveys.

In the current study, Gillings used a technique called ground-penetrating radar, which maps the resistance of the Earth to the sound waves. He found several interesting features: A number of high-resistance objects (presumably buried stones), as well as lower resistance patches (possibly more deeply buried stones or construction debris), along with low-resistance areas (likely destruction pits). The orientation of these buried stones forms a square, Gillings reported in the study, which has not yet been submitted to a journal for peer review.

It turned out that the angular setting of stones that Keiller had discovered formed a stone square that enclosed a circular feature known as the Obelisk. While circular monuments from the late Neolithic period are common, square monuments were oddities at that time, the researchers noted.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The findings could shed light on why the Avebury monument was built — one possibility is that the square demarcates the boundaries of a first house or settlement in the area, which was then used as the center of the inner circle, the researchers speculate in the study.

"The completion of the work first started by Keiller in the 1930s has revealed an entirely new type of monument at the heart of the world's largest prehistoric stone circle, using techniques he never dreamt of. And goes to show how much more is still to be revealed at Avebury if we ask the right questions," Nick Snashall, National Trust archaeologist at Avebury, said in the statement.

Originally published on Live Science.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus