Worm Grows 2 Heads in Space, Surprising Scientists

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The regenerative power of flatworms — which can regrow into complete individuals after they've been cut into pieces — is well-known among scientists. But a group of flatworms that recently visited the International Space Station (ISS) had a few surprises to share when they returned to Earth.

Scientists sent the worms into space to observe how microgravity and fluctuations in the geomagnetic field might affect the worms' unusual ability to regenerate. This was done to better understand how living in space could affect cell activity.

Compared with a group of flatworms that never left Earth, the spacefaring worms showed some unexpected effects from their time off the planet: most notably, the rare sprouting of a second head in an amputated piece of a worm, the researchers documented in a new study. [In Photos: Worm Grows Heads and Brains of Other Species]

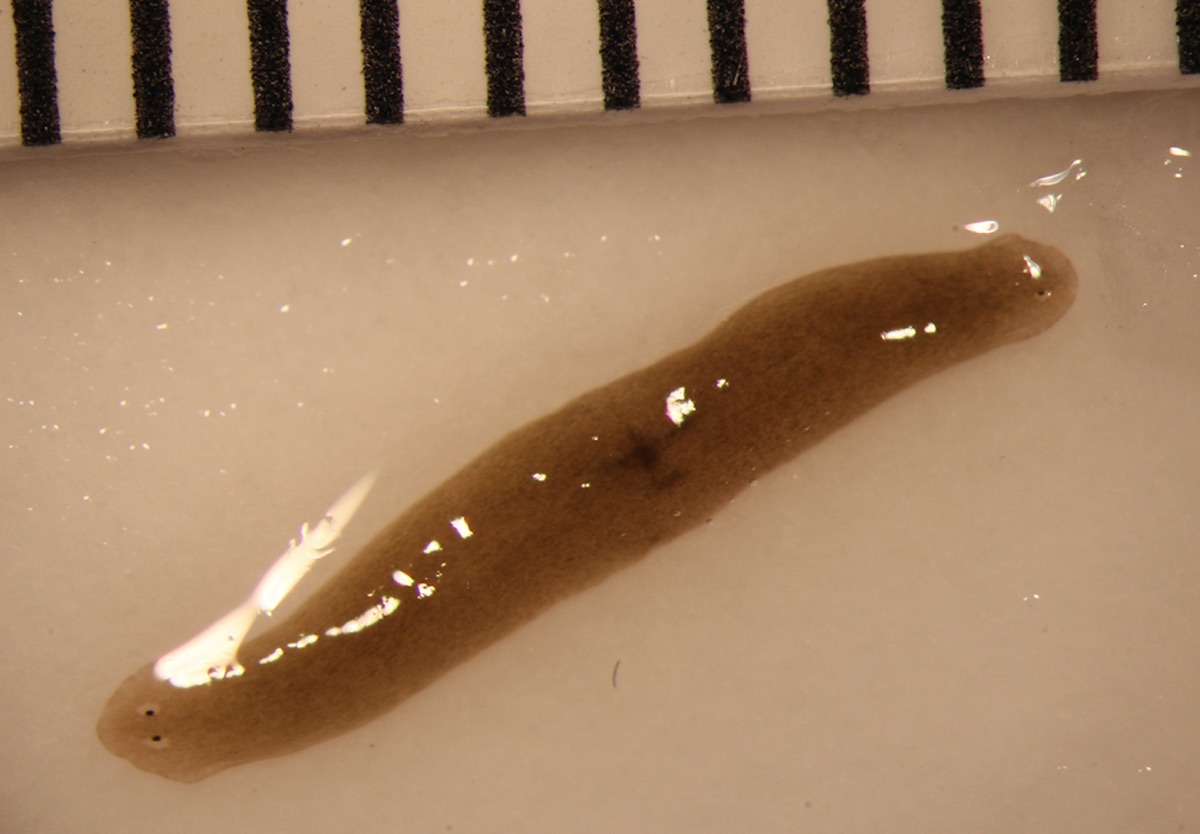

Planarian flatworms (Dugesia japonica) are very flat and tiny, measuring about 0.2 to 0.4 inches (0.5 to 1 centimeter) in length, study co-author Michael Levin, a professor of biology at Tufts University in Massachusetts, told Live Science in an email. (Levin is also the director of the Allen Discovery Center at Tufts and the Tufts Center for Regenerative and Developmental Biology.)

One flatworm could result in multitudes, under the right conditions. Individuals can perform fission — dividing to form two distinct individuals — and severed flatworms can grow new heads or tails, depending on where the body was cut. To find out how factors such as gravity and Earth's magnetic field affect the worms' ability to regrow themselves, scientists sent sets of whole worms and amputated worms to the ISS for five weeks, the study authors wrote. Researchers sealed the worms inside tubes with varying ratios of air and water, and then observed the animals when they came back, the authors wrote.

Return of the regenerating space worms

After the worms returned, the researchers tracked changes in the animals' bodies and in their microbes, comparing the test worms with flatworms that had never left Earth. And the researchers continued observing the worms over 20 months, to see whether any changes were long-lasting.

The scientists found several significant differences between the flatworms that went to space and the Earth-bound worms. For instance, during the first hour of immersion in containers of fresh spring water, the spacefaring worms appeared to experience "water shock"; they curled up and were "somewhat paralyzed and immobile," the researchers wrote, suggesting that the worms underwent metabolic changes while in space. The space-y flatworms exhibited normal behavior after about 2 hours, but further analysis revealed that their microbial communities had changed, hinting at metabolic shifts caused by the unusual conditions the worms encountered on the ISS, the study authors wrote.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Spacefaring worms also demonstrated a change in behavior. When both groups were introduced to illuminated "arenas" in petri dishes, the worms that went to space were less inclined to seek out the dish's darker portion, the scientists found.

But the most dramatic difference was a type of regeneration observed in one of the 15 worm fragments sent to the ISS. That worm returned to the scientists with two heads (one on each end of its body), a type of regeneration so rare as to be practically unheard of — "normal flatworms in water never do this," Levin told Live Science. When the researchers snipped both heads off back on Earth, the middle portion regenerated into a two-headed worm again.

"And these differences persist well over a year after return to Earth!" Levin said. "Those could have been caused by loss of the geomagnetic field, loss of gravity, and the stress of takeoff and landing — all components of any space-travel experience for living systems going to space in the future," he said.

At first glance, these tiny regenerating worms may not appear to share much in common with the human astronauts currently on board the ISS. But the worms offer valuable insights into how living in space can affect cells and microbial communities in organisms, which could help scientists understand the impacts of space travel on human bodies, Levin explained.

"Scientists know a lot about biochemical signals that allow cells to cooperate to build and repair a complex body. However, the physical forces involved in this process are not well-understood," he said.

Studying flatworms could offer insights into how biological systems in living creatures interact with gravity and the geomagnetic field, "which in turn will not only help us optimize future space travel, but will [also] shed light on basic mechanisms that will have implications for regenerative medicine therapies on Earth and in space," Levin added.

The findings were published online today (June 13) in the journal Regeneration.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus