Antikythera Anniversary: Astronomical Computer Still Puzzles After 115 Years

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

What looked like a hunk of corroded metal lying at the bottom of the Aegean Sea near the Greek island of Antikythera turned out to be a piece of a mysterious astronomical calculator. That was 115 years ago, on May 17, 1902, when archaeologist Valerios Stais discovered the bronze bit among other artifacts discovered on the Roman cargo ship called the Antikythera shipwreck.

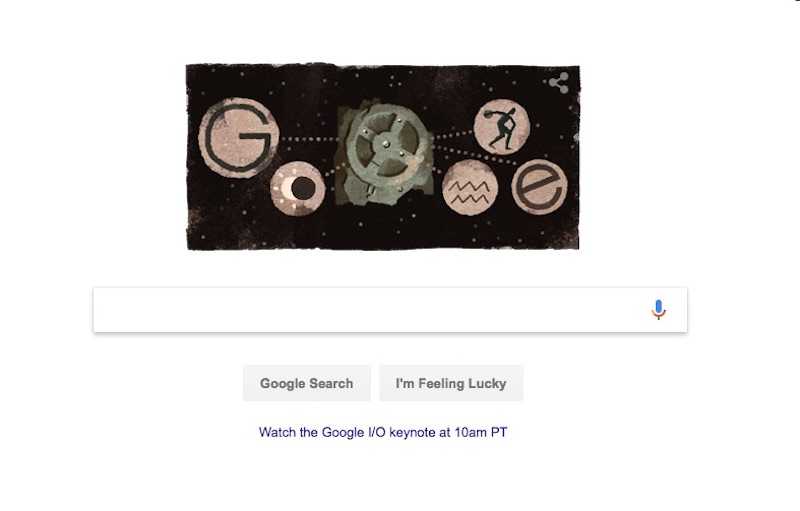

Today's Google Doodle celebrates that discovery with an illustration showing the biggest part of the Antikythera mechanism, which looks like a gear or wheel. Dating to about 85 B.C., or even earlier, the shoebox-size computer is intricate, with dials on the outside and 30 bronze gear wheels inside. Long ago, Greeks could have turned a hand crank on the device to reveal everything from the positions of the sun and the moon and the lunar phases to the cycles of the Greek Olympics. [Photos: Ancient Greek Shipwreck Yields Antikythera Mechanism]

The Antikythera mechanism was also equipped with a dial to predict eclipses. (The Google Doodle includes illustrations for some of these uses, such as the Olympic Games.)

To this day, historians and scientists continue to study the 2,000-year-old computer to reveal more of its secrets. For instance, scientists reported last summer that they found a user's guide of sorts hidden in text on the 82 corroded metal fragments that make up the Antikythera mechanism. Much of the Greek text is unreadable to the naked eye, but with new imaging methods, such as 3D X-ray scanning, scientists have been able to view the once-hidden letters and words.

"Before, we could make out isolated words, but there was a lot of noise —letters that were being misread or gaps in the text," Alexander Jones, a professor of the history of science at New York University, told Live Science last year. "Now, we have something that you can actually read as ancient Greek. We can tell what these texts were saying to an ancient observer."

Jones and colleagues found that those inscriptions on the front and back of the mechanism would have been a key for all of the dials and what they were used for.

"That's where we get the key information that there was a full-blown display of planets moving through the zodiac on the front," Jones said last year. This display, which is now lost, had pointers with small spheres representing the sun, moon and planets known at the time (Mars, Jupiter and Saturn) arranged in a geocentric system with circular orbits around Earth, according to the inscription on the back cover. Researchers had proposed the existence of this feature before, but they never had any physical evidence for it, Jones said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Also last year, archaeologists discovered the 2,000-year-old skeleton of a young man found on the Antikythera shipwreck. The skeleton could divulge the first DNA evidence from the famed wreck, researchers said.

Original article on Live Science.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus