Workers at a nuclear-waste site in Washington state were recently told to hunker down in place after a tunnel in the nuclear finishing plant collapsed, news sources reported yesterday (May 9).

Workers at the Hanford nuclear site were told to either evacuate or shelter in place, and to avoid eating or drinking anything after the tunnel collapsed, according to the Yakima Herald. The U.S. Department of Energy activated an Emergency Operations Center for dealing with the disaster.

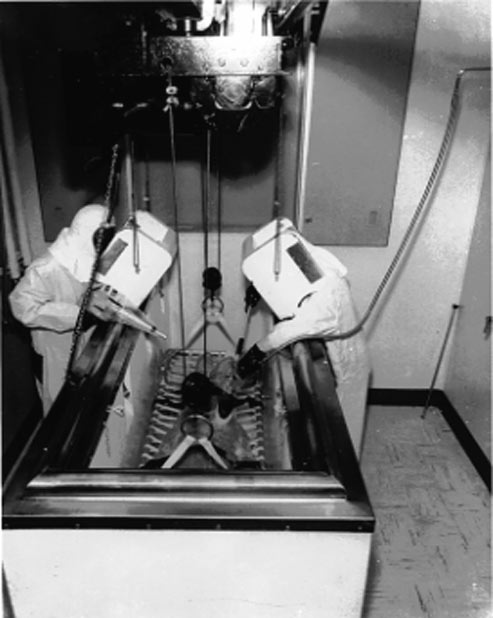

The tunnel was part of the plutonium and uranium extraction facility (PUREX) said to be holding a lot of radioactive waste, including railway cars used to carry spent nuclear fuel rods, news agency AFP reported. At least some of the radioactive waste at the Hanford facility contains radioactive plutonium and uranium, according to the DOE, although at least some of it is also radioactive "sludge" composed of a mixture of radioactive substances. Right now, authorities have not revealed whether radioactive substances have been released or whether people have been exposed any of these contaminants. [Images: Chernobyl, Frozen in Time]

But if people were indeed exposed to the radioactive waste containing plutonium and uranium, what health risks would they face? And how can people minimize their risk of exposure?

Radioactive plutonium and uranium

All radioactive material, as it decays, can cause harm. As unstable radioactive isotopes, or versions of an element with different molecular weights, decay into slightly more stable versions, they release energy. This extra energy can either directly kill cells or damage a cell's DNA, fueling mutations that may eventually lead to cancer.

Plutonium, one of the radioactive substances that may be present at the Hanford site, has a half-life of 24,000 years, meaning that's how long it takes for half of the material to decay into more stable substances. As such, it sticks around in the environment, and in the body, for a long time.

Plutonium exposure can be very deadly for living creatures. A 2011 study in the journal Nature Chemical Biology found that rat adrenal-gland cells ferried plutonium into the cells; the plutonium entered the body's cells largely by taking the natural place of iron on receptors. That study found that plutonium also can linger preferentially in the liver and blood cells, leaching alpha radiation (two protons and neutrons bound together). When inhaled, plutonium can also cause lung cancer.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

However, because the human body still slightly prefers iron to plutonium for its biological processes, that preference could potentially provide avenues for treating plutonium exposure, by flooding such receptors and preventing plutonium from being taken in by the cells, the study authors noted.

In addition, a 2005 study in the journal Current Medicinal Chemistry found that there are some short-term treatments for plutonium exposure. Studies in the 1960s and 1970s identified agents, such as Diethylenetriaminepentaacetic, which can help the body remove plutonium faster. Other drugs, such as ones used to treat iron-processing disorders such as beta-thalassemia, or bone-strengthening drugs that treat osteoporosis, may also be useful for plutonium exposure, the study found.

Uranium, another radioactive element that may be present at dangerous concentrations in the PUREX tunnel, also can have harmful effects on human health. Uranium isotopes have half-lives ranging from 4.5 billion years to 25,000 years.

The biggest health risk people face after being exposed to uranium is kidney damage, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. People exposed to uranium may also experience lung problems, such as scar tissue (fibrosis) or emphysema (large air sacs in the lungs). At high doses, uranium can directly cause kidneys and lungs to fail, according to the CDC. However, studies have found that people who drink well water containing low doses of uranium do not show any marked changes in kidney function.

Like plutonium, uranium emits alpha radiation. Uranium may also decay into radon, which has been tied to an increased cancer risk in several studies, particularly in miners who are exposed to higher levels of the toxin.

It's not clear whether there are other radioactive substances in the Hanford site area, but radioactive forms of iodine and cesium can also cause problems such as thyroid cancer, Live Science previously reported.

Radiation sickness

Overall, radiation from any source increases the risk of cancer, and the cancer risk increases with higher exposures. Extremely high doses of radioactive waste can induce a condition known as radiation sickness, in which the gastrointestinal tract literally bleeds and sloughs off its lining. During the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, 28 emergency workers died directly from radiation poisoning in the three months after the disaster, and rates of cancer in nearby populations increased four to 10 years after the disaster, Live Science reported.

However, exposures in more recent nuclear disasters, such as the nuclear meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi plant, have not typically been high enough to show highly elevated rates of cancer. For instance, a Japanese worker who was exposed to 10 rem (100 millisievert, or mSv), a measurement of radiation, may face a lifetime cancer risk that is elevated by half a percent, Kathryn Higley, director of the Oregon State University Department of Nuclear Engineering and Radiation Health Physics, previously told Live Science. That radiation dose amounts to the levels received with about five CT scans. Most people in the United States receive 0.3 rem (3 mSv) of radiation each year from natural sources, such as the sun, Live Science previously reported.

In addition, studies have found lower rates of cancer in nuclear plant workers than in the general population, likely because these workers tend to be healthier than the people in the nearby population, according to a 2004 study in the French journal Revue Epidemiological Sante Publique. Therefore, untangling a slightly elevated risk of cancer due to radiation exposure from a slightly lower risk due to healthier habits could be tricky, the study noted.

Originally published on Live Science.

Tia is the editor-in-chief (premium) and was formerly managing editor and senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, Science News and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus