Snails That Fly Around the World

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The chicken may have just wanted to get to the other side of the road, but here's a real puzzler:

Why did the snail travel 5,500 miles from Europe to an island in the South Atlantic?

New research reveals that it was most likely stuck to a bird.

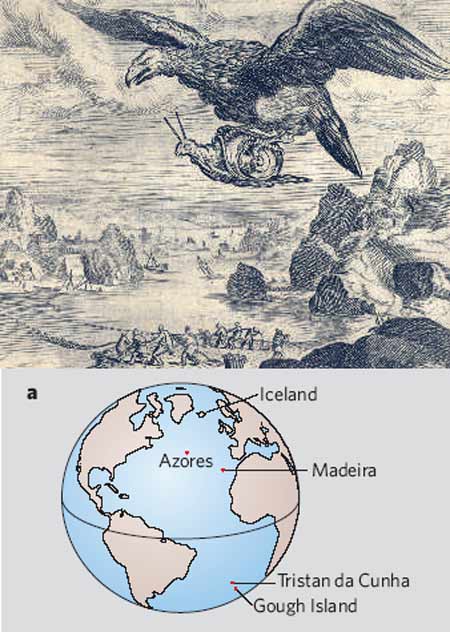

Snails of the genus Balea are found throughout Europe and the Azores, the group of islands in the middle of the North Atlantic, and similar snails can be found on a tiny island chain in the South Atlantic. Because of the enormous distance between these two groups, scientists have long believed they belonged to a different genus, Tristania.

Now, genetic and anatomical analyses show that the Tristania snails are actually members of the Balea genus.

Round-trip

The study indicates that Balea snails somehow traveled from Europe to the Azores and evolved into two different species. Then, some packed up and headed 5,500 miles south to Tristan da Cunha, where they further differentiated into eight more species.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Finally, Balea snails from Tristan returned to Europe, where until recently they have been mistaken as the Balea perversa snails that made that original trip.

The question remains, though, how did these snails cross the ocean?

"Traveling to the South Atlantic is quite problematic for a very pedestrian snail," study co-author Richard Preece of the University of Cambridge told LiveScience.

It seems they didn't go by boat, the preferred mode of transport for some invasive species.

Humans didn't discover Tristan da Cunha until 1506, and didn't permanently settle there until 1816. Even today, these islands are home to only some 300 people. And it seems clear that the snails were around well before then, based on the lengthy period of time it would have taken for these new species to radiate from the original travelers.

"This clearly has nothing to do with human agency," Preece said. "These dispersal events happened long before humans were around."

Sticky solution

If there's one thing Balea snails do exceptionally well, it's produce super-sticky slime. They're very seldom found on the ground, and mostly inhabit trees. Researchers think that the snails get from tree to tree by hitching rides on birds, and the same may be true for stealing a ride to a tropical island.

"I think because they live in trees and are particularly sticky, they're prone to being carried by birds," Preece said.

Identifying the particular bird that served as a snail airline from the north to south Atlantic poses a challenge.

Most of the migratory birds that cross the equator, such as arctic terns and great shearwaters, don't come to shore often.

"Trying to get one of those birds and the snails together is problematic," Preece said. "So I suspect that some type of wading bird, with a cargo of stowaway snails tucked into its feathers, was blown off course by a storm and deposited the snails on these islands."

Hurricanes and other strong storms have been known to blow spiders and insects over the ocean, but Preece thinks this mode of transport is highly unlikely for snails. He also rules out the possibility of them rafting on floating vegetation, partly because the distance is so great, but also because of an experiment by Charles Darwin, who was also curious about how snails island-hop.

"Darwin stuck snails on ducks' feet and submerged them in seawater and found them to die quickly on exposure," Preece said.

All it would take is one snail to start a village, though. Balea snails are hermaphroditic, so they can reproduce all by themselves and release baby snails from their shells.

- Alien Snail Invasion

- Snail Charming Scientist a Real Conehead

- Killer Caterpillar Eats Snails Alive

- Secret Weapons of Small Creatures

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus