Adorable Terror: Wolf-Size Otter Hunted in Ancient China

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A fearsome, wolf-size otter with a large head and a powerful jaw once swam around the shallow, swampy waters of ancient China, likely hunting for clams and other shellfish, a new study finds.

The 6.2-million-year-old beast is among the largest otter species on record, the researchers in the new study said. At 110 lbs. (50 kilograms), the animal would have been about twice the size of the modern-day South American giant river otter (Pteronura brasiliensis) and about four times the size of the Eurasian otter (Lutra lutra), the researchers said.

"This extinct otter is larger than all living otters," said study lead researcher Xiaoming Wang, a curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County in California. [See images of the fearsome wolf-size otter]

Researchers discovered the otter's remains in 2010, after a Chinese and U.S. field team found a nearly complete skull in Shuitangba quarry, located in southwestern China.

"The skull was unlike [that of] any other animals found so far, and that's when we realized that this is something unique and important," Wang told Live Science.

However, piecing the skull together was a challenging feat. "Because the skull was preserved in soft brown coal, it has been badly crushed into a pancake-like shape during the compaction of soft sediments," Wang said.

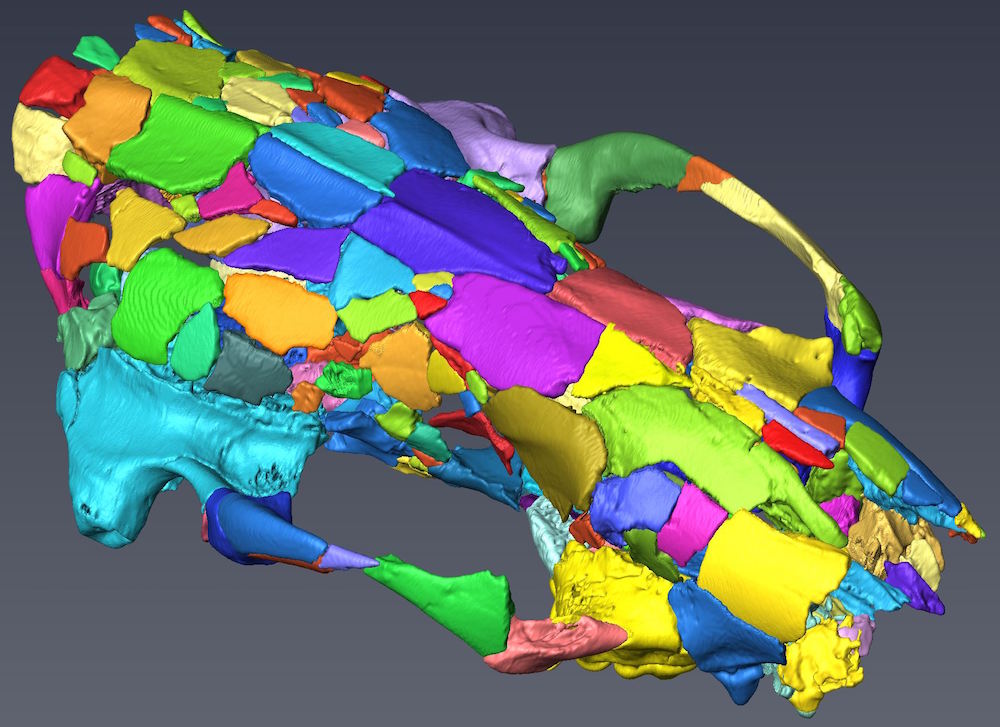

By using a computed tomography (CT) scanner, study co-author Stuart White, a professor emeritus of maxillofacial radiology at the University of California, Los Angeles, was able to digitally restore the skull's 3D shape. Wang compared the reconstruction to "playing a three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle, only to be done by computer mouse rather than by hands."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

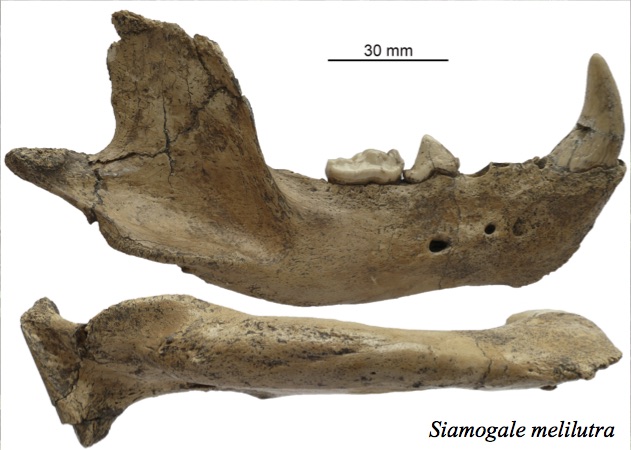

Later, in 2015, the researchers found more fossils in the quarry belonging to the same species; these finds included lower jaws, teeth and several limb bones, Wang said.

Obscure otter

A cranial analysis showed that while the skull of the newly discovered creature is like that of an otter, it has badger-like teeth, Wang said. This inspired the researchers to name the newfound species Siamogale melilutra, because "meles" is Latin for badger and "lutra" is Latin for otter, Wang said.

S. melilutra belongs to an "obscure group of extinct otter in East Asia [that] diverged early from the main otter lineage and formed a distinct group of its own," Wang said. Until now, researchers only knew about this lineage from fossilized teeth found in Thailand, the scientists said.

Moreover, the new findings suggest that S. melilutra belongs to one of the oldest and most primitive otter lineages, one that goes back at least 18 million years, to the European, badger-like animal Paralutra, the researchers said.

It's unclear why S. melilutra was so big, the researchers said. Usually, when carnivores evolve to be large, it's so that they have the strength to subdue prey, Wang said.

"But in our fossil otter, it is more likely a mollusk eater, and its powerful skull and jaws may be designed to crack tough shells of clams," he said.

Wang noted that modern sea otters also crack mollusks. But in addition to using their powerful teeth, these modern species also use tools — that is, rocks — to smash open the shells. [10 Animals That Use Tools]

"Perhaps our fossil otter had not learned to use rocks, and instead [would] apply brute strength to crush hard shells," Wang said.

This question is just one of many that researchers have about S. melilutra, said study co-researcher Denise Su, a curator at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History.

"We are working to answer questions regarding its paleobiology, like, 'How did it swim? How did it move on the ground? Why is it so large?'"

The study was published online today (Jan. 23) in the Journal of Systematic Paleontology.

Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus