Artificial Blood Vessels Grow After They're Implanted

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Researchers have engineered artificial blood vessels that can grow after they are implanted, according to a new study done in lambs.

The blood vessels were engineered to replace real vessels that would normally carry blood from the lambs' hearts to their lungs. The results could one day help to make vessels that could prevent the need for repeated surgeries in children with certain heart defects, although more research is needed to test whether these vessels could eventually be implanted in humans, the researchers said.

Children who have certain heart defects may need surgery to replace the vessels connecting the heart to the lungs. But the reconstructed vessels that are currently used in these surgeries are made of a material that can't grow as the child grows, said study co-author Robert Tranquillo, a professor of biomedical engineering at the University of Minnesota. [10 Amazing Facts About Your Heart]

"There is no material that grows with a person," Tranquillo told Live Science.

As a result, these children may have to undergo five to seven surgeries during their lifetimes, just to keep getting new, larger replacements for the vessels.

In the new study, the researchers wanted to address this problem and create a material that would be capable of growth and that could eventually eliminate the need for these children to have multiple surgeries.

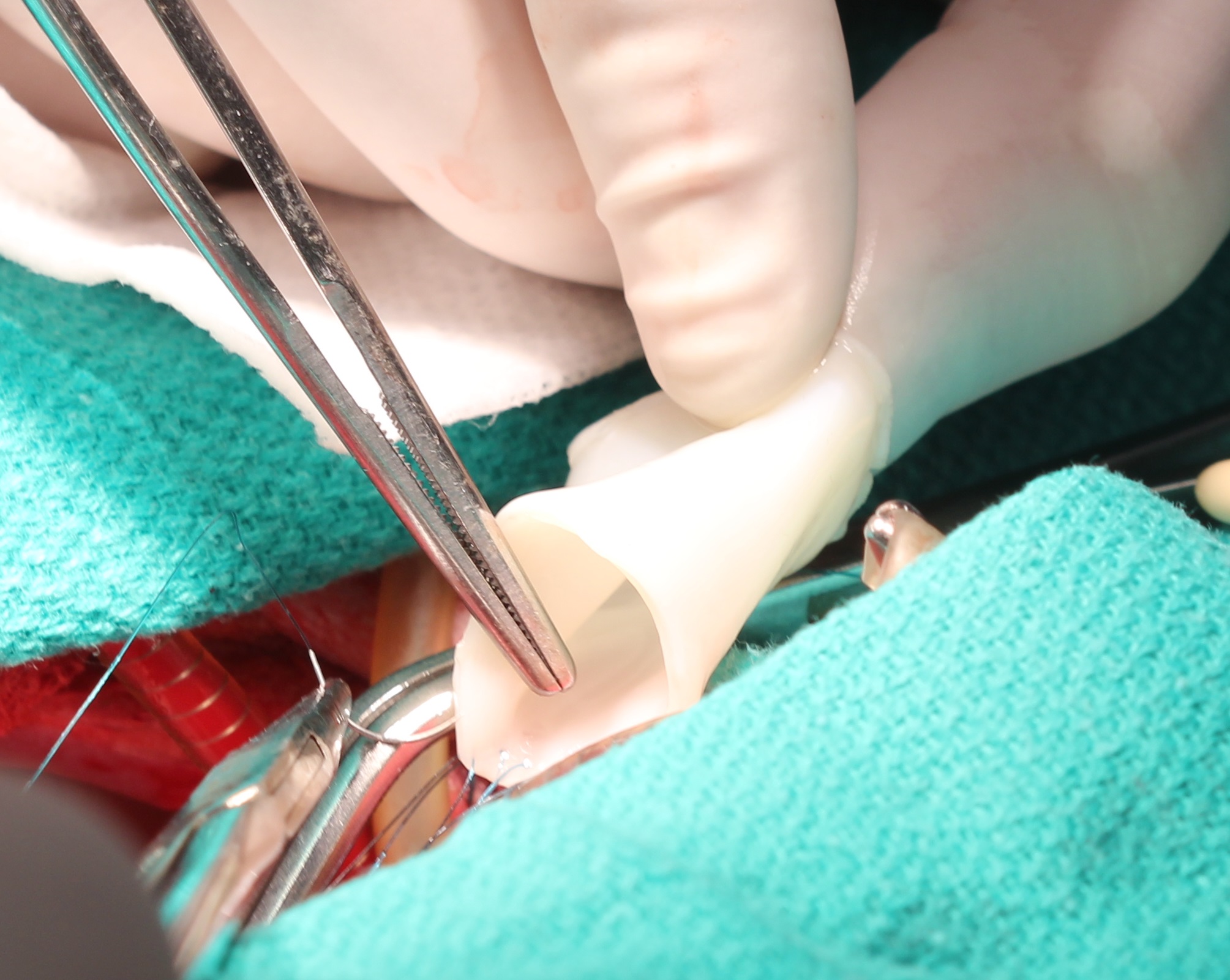

To engineer the artificial blood vessels, the researchers first placed sheepskin cells into a special tube, and then pumped nutrients into the fluid around the cells, allowing the cells to grow. Eventually, the cells formed a sheet that took on the shape of the tube. The pumping caused the cells to stretch and deposit proteins into their surroundings. These proteins would eventually serve as building blocks for the vessels.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Then, the researchers washed the cells away, and all that was left was a tube-shaped protein scaffold. The researchers hoped that if they got rid of the cells, the blood-vessel grafts would not be recognized as foreign bodies and, in turn, would not be rejected by the recipients' immune systems.

Next, the researchers implanted those blood-vessel grafts in three 5-week-old lambs, to replace parts of the vessels connecting the heart and the lungs. They found that the protein scaffolds became populated by the lambs' own cells after transplantation, and grew together as the lambs grew. [Top 3 Techniques for Creating Organs in the Lab]

The researchers followed the sheep until they turned almost 1 year old and were about four to five times larger than they were when the vessels were implanted. The lambs did not seem to experience any negative side effects from the transplants, according to the study, published Sept. 27 in the journal Nature Communications.

Also at that time, the researchers removed the grafted blood vessels from the lambs, and examined the vessels' features. They found that the grafts had grown from relatively small tubes to larger structures that were about 50 percent longer and wider than their original lengths and widths, and were functioning almost like normal arteries in the adult sheep, Tranquillo said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus