Plague: A Scourge From Ancient to Modern Times

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Plague is often associated with the Middle Ages, but the infamous disease wreaked havoc before and after that time, and continues to infect people today. If left untreated, the bubonic plague can have a fatality rate of 50 to 60 percent, according to the World Health Organization. Antibiotics, developed in the 1940s, are effective in treating plague today.

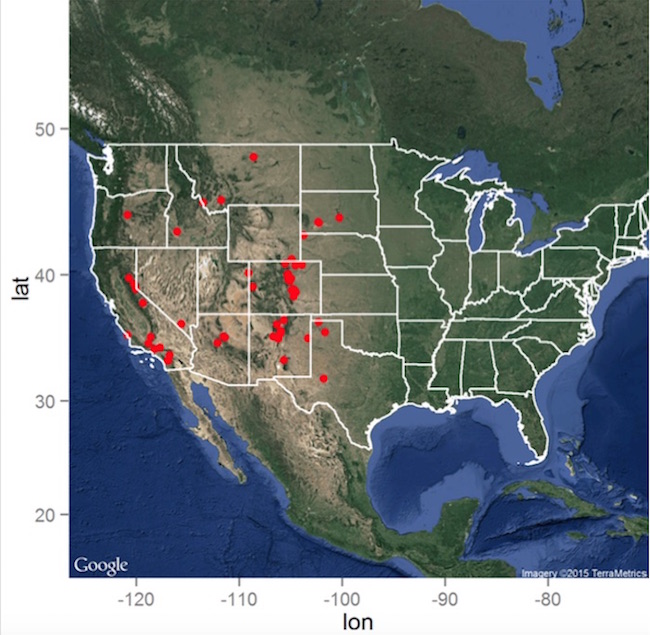

Plague is found on every continent, but currently, plague is most prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa and Madagascar. More than 90 percent of current reported cases are found there, according to a review in PLOS Medicine. More than 1,000 cases of plague have been reported in the United States in the past 100 years.

Plague is more likely to occur in rural areas where people are exposed to wild rodents. It is more common in the rural Western United States than the East, though it is still rare.

What is plague?

Plague is an infection caused by an extremely virulent bacterium, Yersinia pestis, according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Scientist Alexandre Yersin discovered Yersinia pestis in 1894. The bacterium is usually found in rodents and their fleas. Throughout history, urban rats have been the most dangerous plague-carriers to humans. Infected rat fleas can transmit Yersinia pestis to humans through their bites. Wild animals can catch plague through eating infected animals. This can sometimes lead to an outbreak among animals called an epizootic. Plague rates in humans tend to go up after epizootics, according to the CDC.

According to National Geographic, the virulence of Yersinia pestis is due to its ability to disable the host’s immune system. Yersinia pestisinjects toxins into defense cells, leading to the breakdown of the immune system. Then, the bacteria multiply rapidly, infecting the body.

Types of plague

There are three types of plague and all begin with the same basic symptoms. According to the WHO, people with plague usually develop flu-like symptoms three to seven days after being bitten or otherwise infected. These symptoms include fever, chills, body aches, vomiting, nausea and weakness.

Bubonic plague is the most common plague type, according to the WHO. It is caused by the bite of an infected flea, often a rat flea. In addition to flu-like symptoms, patients’ lymph nodes become tender and swollen. The lymph nodes can become visibly inflamed and quite large. The inflamed lymph nodes are called “buboes,” which given the plague its name. When bubonic plague advances, the buboes can become festering open sores.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When Yersinia pestis enters the body, it travels to the nearest lymph node, shuts down the defenses, and replicates itself. This is the first lymph node to become a bubo. If patients are not treated promptly, bubonic plague can spread to other lymph nodes. Bubonic plague rarely spreads from person to person.

Septicemic plague is plague of the blood. It can come from flea bites or direct contact with an infected animal, if the infected materials enter through cracks in the skin. It can also develop from untreated advanced bubonic plague, according to the CDC. Yersinia pestis enters the bloodstream and multiplies there.

In addition to flu-like symptoms, patients with septicemic plague experience extreme weakness, shock and abdominal pain. There can be internal bleeding that often causes skin and other tissues to turn black and die. This necrosis is most often seen on the nose, fingers and toes.

Pneumonic plague is the most deadly form of plague and the only one that can spread from person to person, according to the CDC. Pneumonic plague infects the lungs and can be transmitted through coughs. Occasionally, people get it from the coughs of their pet cats, which are susceptible to plague. Pneumonic plague can also develop from advanced, untreated bubonic plague that spreads to the lungs.

Pneumonic plague causes patients to develop serious pneumonia. Symptoms include fever, chills, weakness, a rapidly developing cough, shortness of breath, chest pain and watery or bloody mucus. It can cause respiratory failure or shock.

Fortunately, pneumonic plague is the least common form of plague, according to the WHO.

Diagnosis and treatment

If a healthcare worker suspects plague, he or she will sample the patient’s blood, sputum or lymph node aspirate and send them for lab tests, according to the CDC. Preliminary results can be ready in less than two hours. Confirmation can take 24 to 48 hours.

Plague is treated with readily available antibiotics. Often, antibiotics are given as soon as samples are taken because the sooner the patient begins treatment the better the chances for full recovery. If the patient has pneumonic plague, people in close contact with him or her may be evaluated, placed under observation and given preventative antibiotics, according to the CDC.

Various plague vaccines have been developed but their effectiveness has been inconclusive and they are no longer available in the United States, according to the CDC.

History of plague

There have been three major plague epidemics throughout human history. According to a history of plague published in Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings, the earliest instance of plague was probably recounted in the Bible. The First Book of Samuel accounts that around 1000 B.C., the Philistines were afflicted with a terrible disease involving swollen lymph nodes.

The Justinian Plague, however, was the first epidemic to be reliably recorded, according to Susan Abernethy, a Colorado-based historian and writer.

Justinian Plague

The Justinian Plague took place from approximately A.D. 542 until 750. It began during the reign of Justinian I, a Byzantine emperor based in Constantinople.

“The origin of the plague is unknown and there is little information available on how often and where the disease broke out in the following centuries,” said Abernethy. Though there are no reliable numbers regarding deaths, there was a significant drop in population. The Byzantine Empire and surrounding Mediterranean areas may have experienced as much as a 40 percent loss in population during the latter half of the sixth century.

The losses in population created worker shortages and a reduced tax base. Labor costs and inflation increased while food production decreased, leading to additional deaths by starvation, Abernethy told Live Science.

The Justinian Plague had a significant effect on European culture, said Robert Wilde, a UK-based historian and writer. At the time of the plague outbreak, the Eastern part of the Roman Empire (Byzantium), was much stronger culturally and militarily than the Western part, which had been without an emperor for some time. “Emperor Justinian had overseen a re-conquest of large areas of the old Western empire. But the plague destroyed these efforts, and weakened Byzantium trade, economy, military and society so much they were reduced forever in size,” Wilde said. Without this plague, Byzantine culture and the Roman Empire might have existed for much longer.

The Black Death

The Black Death occurred throughout Europe during the 14th ;century and killed approximately 25 million people. Bubonic plague spread through rats and fleas, while pneumonic plague spread from person to person. Europe lost between 33 and 50 percent of its population, according to Wilde.

The Black Death originated in China in 1334 and spread west along the trade routes of the Near and Far East, said Abernethy. By the early 1340s, the disease had struck China, India, Persia, Syria and Egypt. Many Europeans heard rumors of a "Great Pestilence" that was making its way across these routes.

"The plague arrived in Europe by sea in October of 1347 when 12 Genoese trading ships docked in the Sicilian port of Messina following a long journey through the Black Sea," said Abernethy. "People gathered on the docks to greet the ships and were horrified to find most of the sailors aboard were either dead or gravely ill. The men were burning with fever, unable to keep food down and delirious with pain. Strangest of all, they were covered with mysterious black boils, which oozed blood and pus. The illness came to be known as the Black Death as a result."

European leaders had no knowledge on how to contain outbreaks of disease. The Sicilian authorities quickly ordered the ships out of the harbor but it was too late. The disease quickly spread.

The Black Death changed Europe’s economy and wealth distribution. The loss of population resulted in larger inheritances, concentrating the wealth. At the same time, wages increased because of greater demand. Rich landowners turned to technology to save money. According to Wilde, the greater wealth concentration was “a massive cause of the Reformation, when money, power and art directly intersected.”

Wilde added, “In many ways the Black Death triggered the start of the evolution of medieval society into modern, but I think it’s important to stress the massive psychological impact these losses had on the survivors, as borne out by much northern art.”

The Modern Plague, or Third Pandemic

The Modern Plague began in China’s Yunnan province in 1855, said Abernethy, and “killed more than 12 million people in India and China alone.”

There were two strains of plague during the Third Pandemic. A bubonic strain spread through transportation of cargo, people and rats across the oceans. A more virulent pneumonic strain was largely confined to Manchuria and Mangolia, Abernethy said.

According to Abernethy, a notable characteristic of the Modern Plague is the amount of research that came out of it. “Scientists working in Asia during the outbreak identified plague carriers and the plague bacillus. Alexandre Yersin, working in Hong Kong in 1894, identified Yersinia pestis … In 1898, French researcher Paul-Louis Simond confirmed the role of fleas as the transporter of the disease. This plague is also more documented than the earlier pandemics.”

Chemical warfare

Plague has been used as a weapon of war throughout history, and national security officials continue to worry about its use as a biological weapon. According to a history published in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases, there are first-hand accounts of Mongol armies catapulting bubonic plague-carrying corpses over the city walls of Caffa, a city in Crimea, in the 1300s. Some scholars believe that this tactic contributed to the Black Death.

The Japanese army experimented on plague and is reported to have dropped plague-infected fleas on areas of China and Manchuria during World War II, according to Baylor University Medical Proceedings. During the Cold War, many countries, including the United States and the Soviet Union, researched plague as a biological weapon, though neither utilized it. After the attacks on September 11, national security officials again began to worry about the threat of bioterrorism, including plague.

According to Johns Hopkins University, a weaponized plague outbreak would look different from a naturally occurring pandemic. The bacteria would likely be released as an aerosol, and the first sign of the attack would be a sudden outbreak. Cases would appear one or two days after the attack and people would die quickly. A 1970 WHO analysis of a worst-case scenario showed aerosol released over a city of 5 million resulting in 150,000 cases of pneumonic plague and 36,000 deaths.

Additional resources

Jessie Szalay is a contributing writer to FSR Magazine. Prior to writing for Live Science, she was an editor at Living Social. She holds an MFA in nonfiction writing from George Mason University and a bachelor's degree in sociology from Kenyon College.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus