Who Owns Britain's Elgin Marbles? (Op-Ed)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

It is lunacy to believe you own the moon, and no amount of tomato juice you spill into the sea will make its water yours. Yet we ask the question “who owns antiquity?” as if it were a sane one.

There is a reason for this. It’s the reason why Dennis Hope, founder of the Lunar Embassy and self-dubbed President of the Galactic Government, is no lunatic but an entrepreneur who has sold over 600m acres of “extraterrestrial real estate” to over 6m people. It’s the reason why Nestlé has rebranded itself as a corporate water steward, while bottling ground water at the expense of local communities.

It’s also the reason why today, on the 200th anniversary of the British parliamentary vote to purchase the sculptures that Lord Elgin sawed off the Parthenon, the British Museum continues to insist that its trustees are legally entitled to the sculptures. And it’s the reason why human rights lawyers, marshalled by Amal Clooney, have once again advised a Greek government unwilling to put forward a legal claim that it should take this museum to court.

'Stones of no value'

In 1801, Elgin was the British Ambassador to the Ottoman court from which he obtained a limited license to collect “some stones of no value” from the Acropolis, with which to adorn his estate back in Scotland. The excised sculpted blocks were shipped back to the UK and in 1811, on the verge of bankruptcy, Elgin offered to sell them to the nation. Five years later, the state bought 15 metopes, 17 pedimental sculptures, and 80 metres of frieze for £35,000 (equivalent to at least £2.4m today, placed in the trust of the British Museum.

Guardian correspondent Helena Smith wrote: “Activists have been counting down to what they call the ‘black anniversary’“ (June 7 2016). Nothing could be further from the truth. Most activists agree that had the parliamentary vote to purchase not been won, the sculptures may well have ended up in the illegal art market and vanished without a trace. The real controversy surrounding the debate concerned the fact that the British government was willing to spend such a huge amount at a time of national famine.

But all that was then and this is now. Among other things, Greece is no longer a subject province of the Ottoman Empire. In 2009 the country opened the New Acropolis Museum, which has been specifically designed to display all of the sculptures, and currently displays plaster casts of the London marbles next to the original Athenian ones.

A recent British Museum press statement claimed that the Parthenon sculptures are “a part of the world’s shared heritage and transcend political boundaries”. Greece’s minster of culture, Aristides Baltas, similarly said that “we do not regard the Parthenon as exclusively Greek but rather as a heritage of humanity”. Yet the British Museum also asserts that the sculptures are “a vital element in this interconnected world collection” and the usually diplomatic Baltas was also quoted as saying:

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

We are trying to develop alliances which we hope would eventually lead to an international body like the United Nations to come with us against the British Museum.

These curious juxtapositions all echo those of Nestlé’s chairman (and former CEO) Peter Brabeck-Letmathe, who claimed that when he said “access to water is not a public right” what he really meant was that “water is a human right” (albeit only the 1.5% of it that Nestlé is content not to buy and re-sell). The New Acropolis Museum currently charges a €5 general admission fee for the “heritage of humanity”. The entrance to the British Museum is of course, free; but it leads to suggested donation boxes, gift shops where one can purchase “Elgin Marbles” memorabilia, overpriced cafeterias, and ticketed special exhibitions.

Parthenon regained

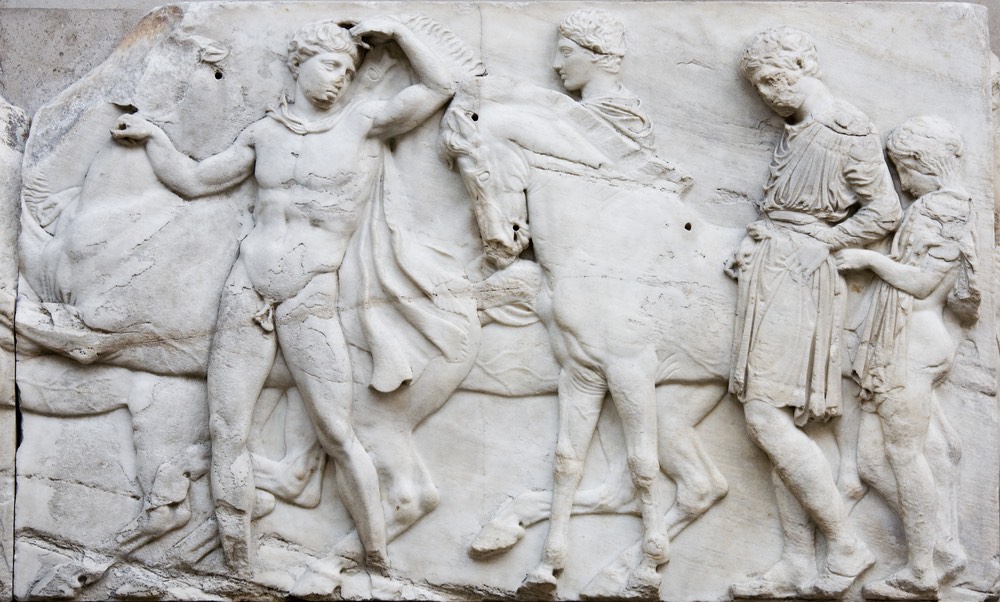

The Parthenon marbles form an integral part of a larger whole, a temple dedicated to Athena whose frieze, metopes, and pediments variously depict her birth, the Panathenaic procession, the sack of Troy, and an array of mythological fights and contests.

There is no other example of a piece of art as crudely dismembered as the Parthenon, with even the heads and bodies of individual sculptures located in different countries (a few rogue pieces somehow ended up in the Louvre and other European museums which have yet to make any gestures of return). If the missing sculptures and fragments of this aesthetic travesty were to be reunited with those in the New Acropolis Museum, visitors could study them as one entire whole, with a direct view of the monument to which they belong.

The time is right for all surviving sculptures to be reunited under this single roof. They should be displayed, for free, in a joint Greek and British international museum. This bicentenary provides the perfect opportunity for the two nations to collaborate instead of bicker over ownership. The British Museum would be praised worldwide for all its actions, culminating in a collaborative partnership that genuinely benefits humanity. It is high time that ownership of the past became a thing of the past and we began to think in terms of joint custody instead.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus