'Poop Transplant' Changes Play Out Over Several Months, Study Finds

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

SAN DIEGO — Patients who undergo a "poop transplant" to treat severe diarrhea often see their symptoms get better within days, but their gut bacteria continue to undergo dramatic changes for at least three months afterward, a new study finds.

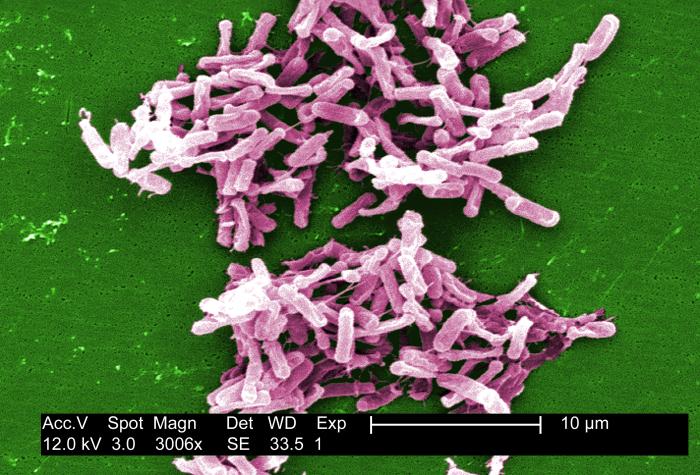

Researchers analyzed the gut bacteria of eight patients who had Clostridium difficile, a difficult-to-treat bacterial infection that can be life-threatening. After several earlier treatments for their infection didn't work, all of the patients underwent a procedure called fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), in which fecal matter from a healthy donor is delivered into a patient's colon, in order to restore a better balance of bacteria within the gut.

On the day of the transplant, the patients had significantly less diversity in their gut bacteria, in terms of the number and types of bacteria, compared with the donors' gut bacteria, the researchers found.

And although most patients' symptoms went away within 48 hours of the procedure, the diversity in their gut bacteria was still quite different from that of the donors after a month, said study co-author Dr. Daniel Martin, a gastroenterology specialist at OSF Saint Francis Medical Center in Peoria, Illinois.

It wasn't until three months after the transplant that the diversity in patients' gut bacteria resembled that of the donors, said Martin, who presented the findings here Saturday (May 21) at Digestive Disease Week, a scientific meeting focused on digestive diseases. [5 Ways Gut Bacteria Affect Your Health]

People often think that FMT works because the healthy and diverse gut bacteria of the donor work quickly to take over the patient's colon and resolve their symptoms, Martin said. But the new findings suggest that this is not actually the case, and rather that the patients' symptoms go away long before the overall balance of their gut bacteria starts to look like that of the donors.

"Patients' symptoms have resolution very quickly after a fecal transplant," Martin told Live Science. However, over several months, "the [gut] flora [bacteria] that those patients have dramatically changes — the diversity changes, the type of flora that they have in their GI tract changes — and it takes up to 90 days for the recipients' flora to mirror a diversity of the donor flora," Martin said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Diversity in the gut flora is important for long-term health and success after an FMT, but it's possible that specific groups of bacteria play a bigger role than previously thought in helping patients' symptoms go away immediately after the transplant, Martin said.

Now, the researchers are working to identify which groups of bacteria may be important for patients' symptom resolution after the transplant. It's also possible that other factors, such as a patient's immune response to the donor bacteria, are playing a role in the quick resolution of patients' symptoms, Martin said.

Ultimately, researchers want to identify a subset of bacteria that they could give to patients with C. diff — in pill or liquid form — instead of performing a fecal transplant, Martin said.

In a 2013 study, researchers processed donor fecal matter until it contained only bacteria that they could put in a pill, and found that the pills were well tolerated by patients with Clostridium difficile.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus