Mysterious South American Mounds Are Made of Worm Poop

Large, mysterious mounds of soil found in the tropical grasslands of Los Llanos in South America finally have a scientific explanation: giant worms.

The mounds, found near the Orinoco River in Columbia and Venezuela, are called surales. Now, researchers have discovered that half of the mass of these dense soil piles is composed of earthworm excrement. The mounds form when worms — many reaching more than 3 feet (1 meter) in length — digest the dirt in the shallowly flooded grasslands of Los Llanos, researchers report today (May 11) in the journal PLOS ONE.

As they feed on the organic material in the soil, the worms excrete "casts," which are essentially worm poop. The casts pile up to form mounds 1.6 feet to 16.4 feet (0.5 to 5 m) in diameter. The surales can grow as high as 6.5 feet (2 m) tall. [14 Strangest Sites on Google Earth]

"This exciting discovery allows us to map and understand how these massive landscapes were formed," study researcher José Iriarte, an archaeologist from the University of Exeter, in the United Kingdom, said in a statement. "The fact we know they were created by earthworms across the seasonally flooded savannahs of South America will certainly change how we think about human versus naturally built landscapes in the region."

Surales landscapes are striking. From air, they look bumpy and lumpy. On the ground, this view coalesces into a marshy grassland consisting of large, vegetated mounds separated by swampy ditches. Though people have generally attributed the soil patterns to worms, alternative explanations included termite activity or erosion, Iriarte and his colleagues wrote. No one had ever ruled these explanations out. In fact, no one had ever scientifically described the surales landscape and surales formation at all.

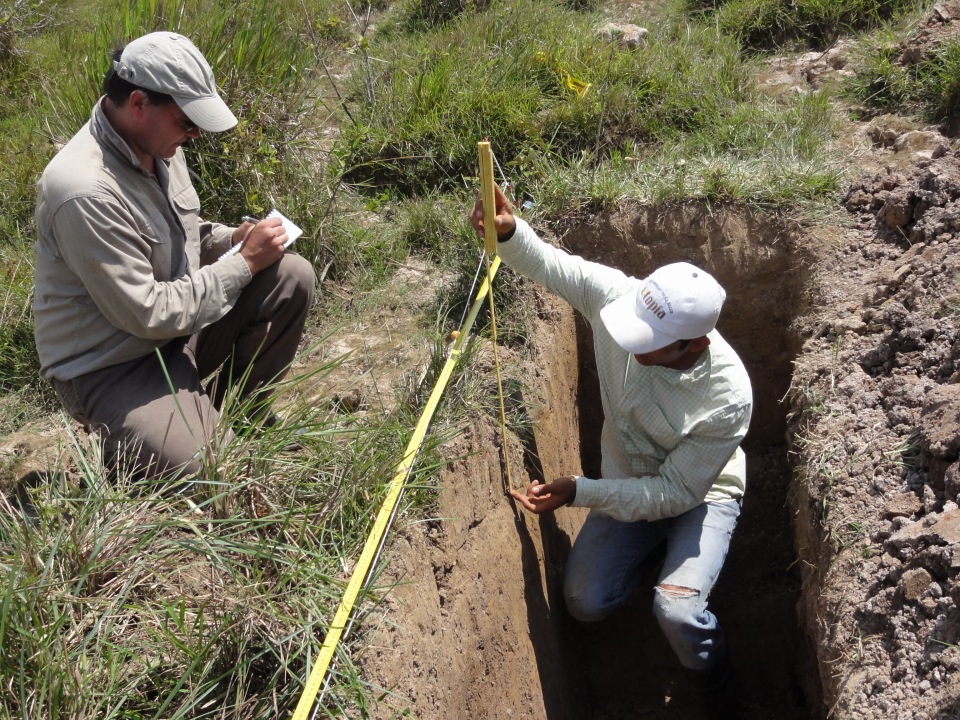

In their new study, the researchers used aerial and satellite photography as well as field studies of soil properties and soil organisms to examine the regular spatial pattern of the surales. The analyses found no evidence of termite activity, but plenty of busy earthworms — nine species, to be exact. A single species of giant Andiorrhinus worm was most prominent, making up almost 93 percent of worm biomass (meaning the total mass of worms at the field sites). Worms were much more prevalent in surales mounds than they were in the ditches surrounding them, and sometimes they couldn't be found in the ditches at all, though their burrows were present, the researchers said.

The mounds were about half earthworm casts by volume, the researchers found, and that percentage was higher than it was in the between-mound ditches, where the soil comprised between 0 percent and about 35 percent earthworm casts. Andiorrhinus, a true giant of a worm that can grow more than 3 feet (1 meter) long, appeared to be the main mound builder, Iriarte and his colleagues reported. The worms forage in shallowly flooded soils and then crawl to higher ground to breathe and excrete. Their casts form towers, which the worms return to again and again, perhaps over many generations, the researchers wrote. As the towers grow into mounds, the worms excavate the basins around them in search of more food, creating a self-perpetuating loop of lower and higher ground.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

More questions remain, the researchers wrote, such as what happens when mounds eventually erode and collapse. Worm landscape formations are also known to be present in South Africa, Uganda and New Guinea, Iriarte and his colleagues wrote.

"Comparative study of these landscapes and the worms that make them would be most enlightening," they wrote.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.