Purple Digging Frog Undergoes Amazing Transformation

A strange purple species of frog that lives most of its life underground undergoes a drastic change from rock-clinging tadpole to grown-up digger, new research finds.

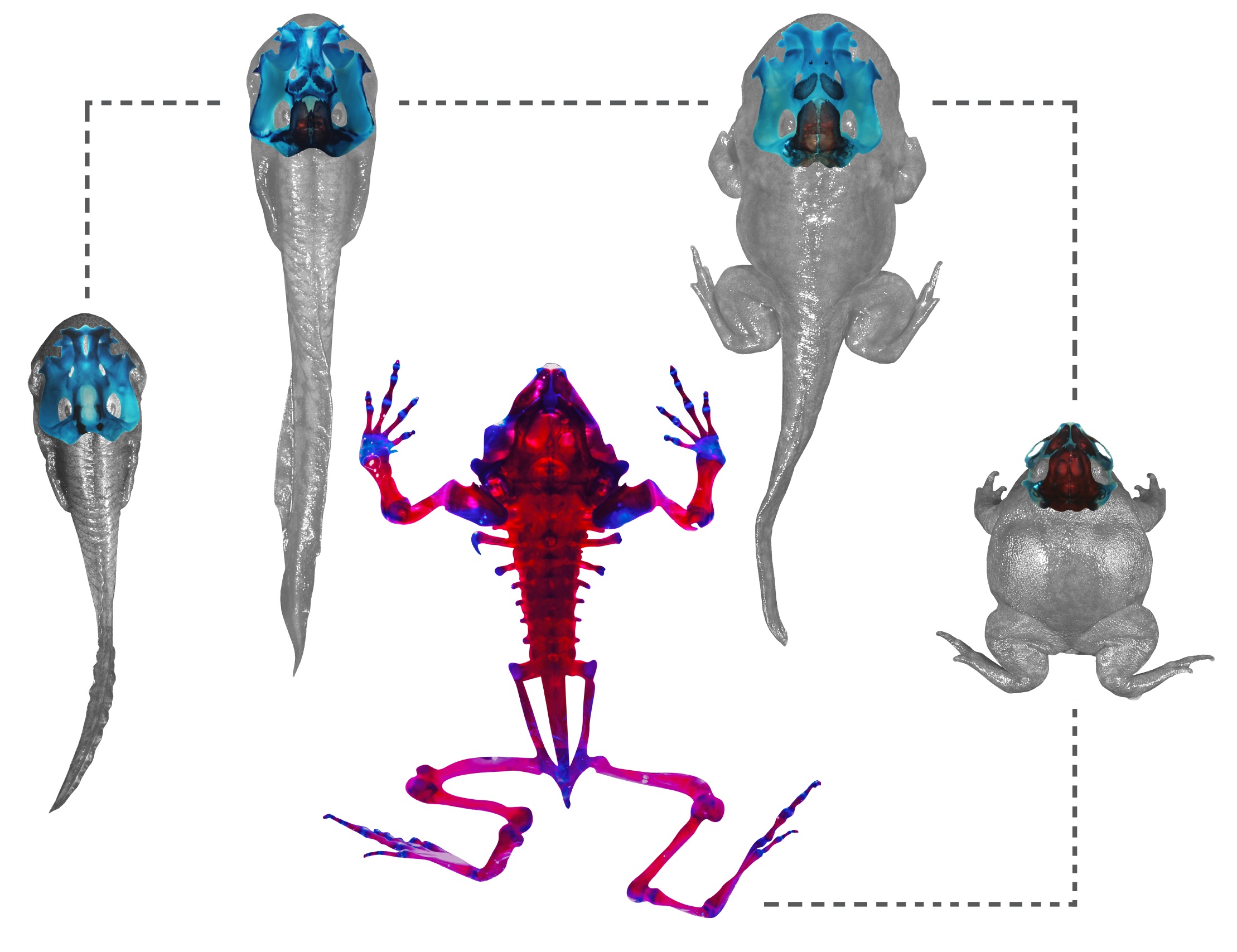

While most frog tadpoles swim freely in the water, the Indian purple frog (Nasikabatrachus sahyadrensis) spends its tadpole time clinging, with its suckerlike mouth, to the undersides of rocks. It then metamorphoses dramatically into an adult that burrows underground and stays there, emerging only to breed. Now, a new study published in the journal PLOS ONE reveals that to complete this transformation, the frogs keep their suckerlike larval mouthparts much longer than other frogs, and develops strong digging arms and a wedge-shaped skull for burrowing.

"For these remarkable frogs, being clinging and digging specialists seems to have enabled them to survive since the Jurassic," study co-author Madhava Meegaskumbura, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Peradeniya in Sri Lanka, said in a statement. [Photos: Cute and Colorful Frogs]

Unusual amphibian

The Indian purple frog has a lavender-shaded body and a hoglike nose. It was only discovered in 2003, according to the Evolutionary Distinct and Globally Endangered (EDGE) of Existence conservation group. Growing to a length of about 2.8 inches (7 centimeters), the frog is found only in India's Western Ghats.

As the only known living representative of the Nasikabatrachidae family, the Indian purple frog is of evolutionary interest to researchers. The species is also relatively unknown because of its underground lifestyle in the adult phase. Most initial observations focused on tadpoles.

Now, Meegaskumbura and colleagues have collected and studied tadpoles in various stages of metamorphosis to better understand how these frogs develop. They used staining techniques to measure bone and cartilage changes and took external measurements of the tadpoles' body parts.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Specialist diggers

Their findings reveal an animal that changes dramatically during development. The tadpole head is as wide as it is long. As the animal reaches the digging froglet stage, the skull widens at the back and narrows toward the front, creating a sort of spade shape well-adapted for digging. The suckerlike mouth persists well into development, sticking around as the limb bones grow and harden. This enables the developing tadpoles to keep clinging to rocks in the stream before they're ready to take on the challenge of digging, the researchers found.

The frogs actually go underground before metamorphosis is complete, the researchers wrote. They dig predominantly with their hind feet, but may use their pointy heads to push through the soil once underground, searching for insect meals.

"This relic from the Jurassic era reminds us that extreme specialization can be an effective survival strategy over evolutionary time," the researchers wrote.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.