Does Zika Cause Microcephaly? CDC Seeks More Answers

Right now, researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) are collaborating with researchers in Brazil studying Zika virus. The scientists aim to figure out definitively whether the rapidly spreading mosquito-borne virus is harming the developing brains of fetuses, leading to infants born with smaller heads and smaller brains.

In a recent press briefing, CDC Director Dr. Thomas Frieden said that "with each passing day, the association between the Zika virus and microcephaly is looking stronger and stronger."

Now, to further investigate whether there is indeed a cause-and-effect link between the virus and microcephaly, researchers will use a key type of research study called a case-control study, Frieden said.

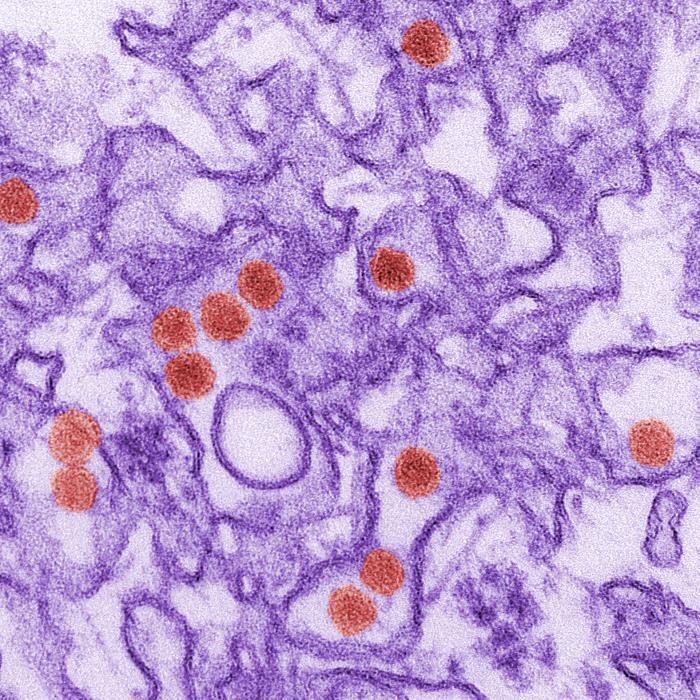

Early evidence of a causal link is emerging: The CDC recently analyzed specimens of brain tissue collected from two infants with microcephaly in Brazil who died shortly after birth, and two pregnancies that ended in early miscarriage. All four mothers had signs of Zika infection, such as fever and rash, in the first trimester of pregnancy.

Those lab results showed the presence of Zika virus in the brain tissues of the babies and placental tissues from the miscarriages. This suggested a strong connection between in-utero exposure to the Zika virus and microcephaly, according to a CDC report published on Feb. 10. [Zika Virus News: Complete Coverage of the 2016 Outbreak]

To further investigate a causal link between the Zika virus and microcephaly, one of the key methodologies that researchers will use is a case-control study, Frieden said. A case-control study could provide stronger evidence of a link than the preliminary research gathered so far, he suggested.

Using this type of study, the researchers will identify infants who definitely have microcephaly, considered the "cases," and babies who don't have the birth defect, considered the "controls." Once the investigators have a large enough number in each group, the scientists can then compare many of the characteristics of the infants and their mothers, looking at environmental exposures and laboratory test results, to tease out which differences between the groups may signal a causal connection.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Searching for clues

Currently, the CDC is working to rapidly accumulate information and carefully evaluate all the scientific evidence that could help establish the full picture of the link between Zika and microcephaly, said Peggy Honein, an epidemiologist at the CDC's National Center for Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities in Atlanta.

A planned case-control study of Zika and microcephaly is starting soon in Brazil, and a field team from the CDC has traveled there to help in this research, Honein said. The CDC also hopes to start a similar study in Colombia, and is working on reviewing cases in Puerto Ricol, Honein added.

For the Brazil study, the researchers hope to enroll a total of 400 to 500 women who had babies in the last few months, including both those babies with microcephaly (as cases), and those without the condition (as controls), Honein told Live Science.

The researchers will examine risk factors, such as whether the women had symptoms of the Zika virus during their pregnancies, which trimester they had these symptoms, and whether the women had other potential prenatal exposures, such as to rubella or environmental toxins, that might be strongly associated with an adverse birth outcome, including microcephaly, Honein said.

Whenever possible, researchers will also look to see if there is any lab confirmation of these infections, but the scientists may need to base their assessment of whether the infection was present on the symptoms experienced by the women, Honein said.

Between mid-2015 and January 2016, about 4,800 infants born in Brazil were reported as having suspected microcephaly, whereas fewer than 200 cases were reported per year in the country prior to the Zika outbreak, according to a recent paper in the journal Lancet. The outbreak began in the northeast region of Brazil in early 2015.

However, although there has been a huge increase in suspected cases of microcephaly, the number of actual microcephaly cases in Brazil may be much lower. The number may drop when lab tests, imaging exams and rigorous investigations by health professionals are completed, the authors of the Lancet study said.

Why case-control studies could give clues

Microcephaly can be a difficult birth defect to monitor, because there are different criteria and definitions used to diagnose it, Honein said. She also said that researchers are looking at examples of other viral illnesses that can cause health problems in infants if the infections occur during pregnancy, such as rubella and cytomegalovirus infections. The researchers are trying to use this information to understand more about the Zika virus and its possible mechanisms of causing microcephaly. [Video: What You Need to Know About Zika Virus]

Case-control studies are widely used, especially for studying infectious diseases, said Stephen Morse, a professor of epidemiology at Columbia University's Mailman School of Public Health in New York City, who specializes in studying emerging infectious diseases. Such studies are easy to do and are efficient for gathering data for rarer diseases that have a relatively small number of cases, he said.

Case-control studies are valuable when researchers want some quick answers, and the studies are an appropriate place to start accumulating information in these circumstances, Morse told Live Science. "But the trick is finding appropriate matched controls as a comparison group," he explained.

Other types of studies — such as cohort studies, which are used to evaluate the cause of a disease in a group of people over time based on their exposure to risk factors — can take a long time to complete for a rare disease, such as microcephaly, Morse said. A case-controlled study could probably be completed in a few months, he said.

Learning more information from a case-control study can help strengthen the evidence of a causal relationship between Zika infections in pregnant women and microcephaly, Morse said. Researchers will collect information from pregnant women in Brazil about numerous factors: their age; socioeconomic status; living conditions; nutritional status; exposure to toxins during pregnancy, such as pesticides or lead; and infections experienced during pregnancy. By doing so, the researchers can sort out whether the Zika virus alone or in combination with other risk factors may be contributing to this birth defect, he explained.

Little is currently known about the prevalence of Zika virus infections in the Brazilian population at large or in pregnant women, so there is a need to understand what percentage of pregnant women who were exposed to the Zika virus had babies born with microcephaly, Morse said.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Cari Nierenberg has been writing about health and wellness topics for online news outlets and print publications for more than two decades. Her work has been published by Live Science, The Washington Post, WebMD, Scientific American, among others. She has a Bachelor of Science degree in nutrition from Cornell University and a Master of Science degree in Nutrition and Communication from Boston University.