'Schizophrenia Gene' Discovery Sheds Light on Possible Cause

Researchers have identified a gene that increases the risk of schizophrenia, and they say they have a plausible theory as to how this gene may cause the devastating mental illness.

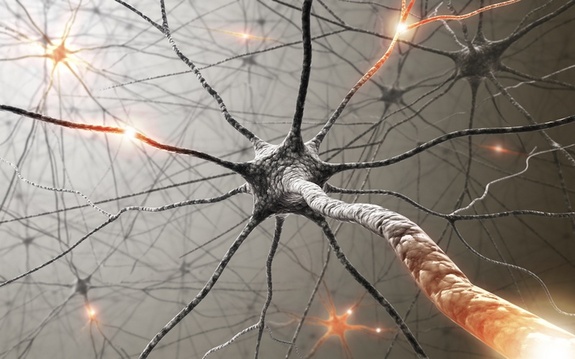

After conducting studies in both humans and mice, the researchers said this new schizophrenia risk gene, called C4, appears to be involved in eliminating the connections between neurons — a process called "synaptic pruning," which, in humans, happens naturally in the teen years.

It's possible that excessive or inappropriate "pruning" of neural connections could lead to the development of schizophrenia, the researchers speculated. This would explain why schizophrenia symptoms often first appear during the teen years, the researchers said.

Further research is needed to validate the findings, but if the theory holds true, the study would mark one of the first times that researchers have found a biological explanation for the link between certain genes and schizophrenia. It's possible that one day, a new treatment for schizophrenia could be developed based on these findings that would target an underlying cause of the disease, instead of just the symptoms, as current treatments do, the researchers said.

"We're far from having a treatment based on this, but it's exciting to think that one day, we might be able to turn down the pruning process in some individuals and decrease their risk" of developing the condition, Beth Stevens, a neuroscientist who worked on the new study, and an assistant professor of neurology at Boston Children's Hospital, said in a statement.

The study, which also involved researchers at the Broad Institute's Stanley Center for Psychiatric Research at Harvard Medical School, is published today (Jan. 27) in the journal Nature. [Top 10 Mysteries of the Mind]

Schizophrenia risk

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

From previous studies, the researchers knew that one of the strongest genetic predictors of people's risk of schizophrenia was found within a region of DNA located on chromosome 6. In the new study, the researchers focused on one of the genes in this region, called complement component 4, or C4, which is known to be involved in the immune system.

Using postmortem human brain samples, the researchers found that variations in the number of copies of the C4 gene that people had, and the length of their gene, could predict how active the gene was in the brain.

The researchers then turned to a genome database, and pulled information about the C4 gene in 28,800 people with schizophrenia, and 36,000 people without the disease, from 22 countries. From the genome data, they estimated people's C4 gene activity.

They found that the higher the levels of C4 activity were, the greater a person's risk of developing schizophrenia was.

The researchers also did experiments in mice, and found that the more C4 activity there was, the more synapses were pruned during brain development.

Molecular cause?

Previous studies found that people with schizophrenia have fewer synapses in certain brain areas than people without the condition. But the new findings "are the first clear evidence for a molecular and cellular mechanism of synaptic loss in schizophrenia," said Jonathan Sebat, chief of the Beyster Center for Molecular Genomics of Neuropsychiatric Diseases at the University of California, San Diego, who was not involved in the study.

Still, Sebat said that the studies in mice are preliminary. These experiments looked for signs of synaptic pruning in the mice but weren't able to directly observe the process occurring. More detailed studies of brain maturation are now needed to validate the findings, Sebat said.

In addition, it remains to be seen whether synaptic pruning could be a target for antipsychotic drugs, but "it's promising," Sebat said. There are drugs in development to activate the part of the immune system in which C4 is involved, Sebat noted.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.