Ancient Marine Reptiles Flew Through the Water

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The ancient, four-flippered plesiosaur didn't swim like a fish, whale or even an otter — but instead like a penguin, a new study finds.

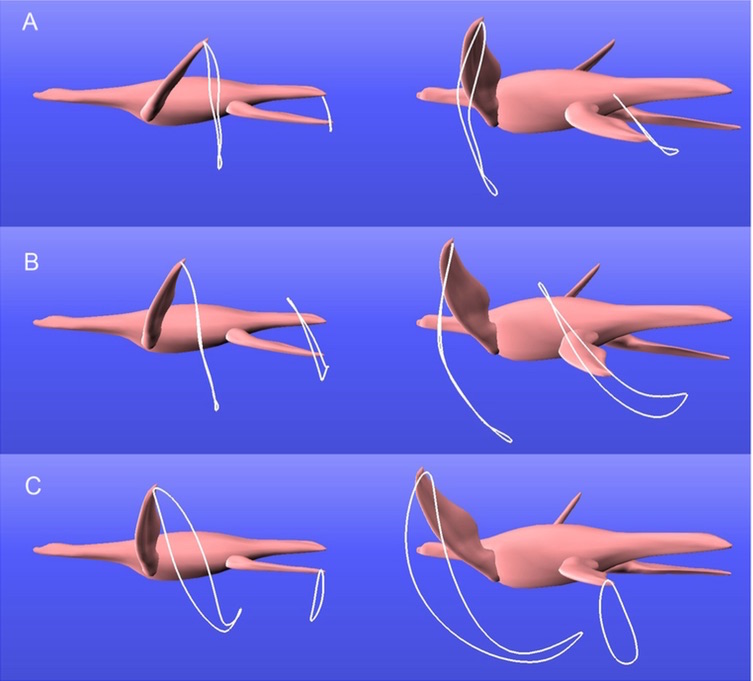

Plesiosaurs, giant marine reptiles that lived during the dinosaur age, likely propelled themselves forward underwater by flapping their two front flippers, much like penguins do today, the researchers said. The paleo-giants probably didn't rely much on their back flippers for propulsion, as that movement would've only marginally increased their speed, computer simulations showed.

"This is the first time plesiosaur locomotion has been simulated with computers, so our study provides exciting new information on how these unusual extinct animals may have swum," said study co-author Adam Smith, a curator of natural sciences at Wollaton Hall, Nottingham Natural History Museum in the United Kingdom. [Photos: Uncovering One of the Largest Plesiosaurs on Record]

The study began when Jie Tan, a graduate student at the Georgia Institute of Technology, began creating computer models and simulations that captured the movements of modern animals. After designing virtual simulations of moving frogs, turtles, eels and manta rays, Tan turned to imaginary creatures. But he wanted another challenge, so he chose an extinct beast for his next project, said study senior author Greg Turk, a professor of computer science at Georgia Tech.

Plesiosaur locomotion has puzzled scientists since the reptiles were first discovered in 1824, because there aren't any modern animals that look like them. Even marine turtles, which have two large front flippers, are no match, because unlike plesiosaurs, turtles have tiny back flippers.

"I did some poking around and found that plesiosaurs have this weird body plan," Turk said. "There isn't any agreement in the paleontology literature about how they swam."

To investigate, the team of computer scientists and paleontologists built a computer model based on Meyerasaurus victor, an 11-foot-long (3.4 meters) plesiosaur discovered in a Lower Jurassic formation in Germany. The scientists placed pivot points on the model's legs wherever the real-life M. victor had joints, but they kept the model's neck and tail rigid, Turk said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We weren't looking for what contribution the tail motion had," Turk told Live Science. "There are hints that some plesiosaurs might have had a little bit of a tail fin, but that's not something we looked into."

The researchers ran about 2,000 simulations to identify the most efficient way the plesiosaur could have swum. In the end, they found that if plesiosaurs flapped their front flippers up and down, the animals could have efficiently propelled themselves forward with every up and down stroke.

"Plesiosaurs flew underwater using their winglike flippers," Smith said. "The front flippers were the powerhouse providing most of the thrust, while the rear flippers provided less thrust and may have been used for stability and steering instead."

This technique, if accurate, clearly worked for plesiosaurs; the reptiles reigned as marine apex predators for 135 million years, until the asteroid event wiped them out some 66 million years ago, the researchers said.

The study was published online yesterday (Dec. 17) in the journal PLOS Computational Biology.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the managing editor at Live Science. She also runs the archaeology section and the Life's Little Mysteries series. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus